|

|

|

|

| |

In last week’s installment of Reread, we revisited a Tom Wolfe story where he bops around Los Angeles, soaking up sun and (he suggests) the culture of America’s future: see-through dresses, a pretty good play about race, a DJ whom Wolfe calls the Human Moon. A few weeks later, New York published another dispatch from California, again under a headline about Life Out There. This time, though, it was a more targeted appreciation of West Coast architecture, and not just any architecture but one form: the roadside neon sign.

|

|

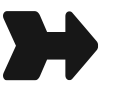

“Electro-graphic architecture,” Wolfe called it, and his essay argues for the giant pole-mounted neon extravaganza as an indigenous American art form. Wolfe being Wolfe, he contrasts these mega-installations with the (in his reading) anodyne, depleted, joyless minimalist fine art of Dan Flavin, who was growing famous for work made principally of fluorescent light tubes, and in particular Billy Apple, who had recently shown his neon sculptures in New York. “Frankly, I’m embarrassed for the guy!” Wolfe writes in absolute glee. “All I can think of is that I could walk over a few blocks to almost any intersection along the avenues on the West Side or drive out Route 22 in New Jersey and see some common commercial electric signs that do it better … There’s not a drive-in or all-night cafeteria or bar & grill in the lot that doesn’t give the glories of electric tubing a better ride.” He was especially taken with an enormous, animated Buick dealership sign in San Diego, and no wonder.

|

|

Wolfe’s views about art and architecture sometimes push the line between anti-pretension and anti-intellectualism, and he could get enthusiastic about some pretty schlocky stuff. But on this particular topic, the architectural Establishment fully agrees with him. A couple of years after this story appeared, Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown published their landmark 1972 book Learning From Las Vegas, which urged architects to embrace (albeit cautiously) putatively junky vernacular building forms and made a particular point of examining Las Vegas’s giant neon spectaculars. Their book was one of the foundational texts that gave us what’s now known as postmodern architecture. Others began to embrace showy bits of Americana: the Googie restaurants of Southern California, weird little roadside novelties shaped like milk bottles or frankfurters. Today, the exuberant buildings and signs from that period that remain intact — and they have grown precious, because they seemed unworthy to so many people for decades and were therefore demolished — are often the subject of preservation fights and pickets when they’re under threat. For those that do have to come down, there’s the Neon Museum in Las Vegas, a warm dry yard in the desert where retired signs roam free.

|

|

|

— Christopher Bonanos, city editor, New York

|

|

![]()

|

|

Photo: Hugo Yu

|

| |

|

Have feedback for us? Reach us at [email protected]. If you enjoyed this newsletter, forward it to a friend. If someone forwarded this to you, you can sign up here. To discover more subscriber-only newsletters, click here. For more from our archives, follow us on Instagram at @oldnymag.

|

|

|

|

|