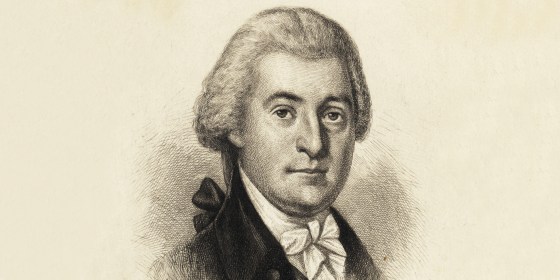

Donald Trump is the first U.S. official to be impeached twice — but Sen. William Blount was the first to be impeached at all.

In papers filed in Trump's Senate trial, expected to start next week, House impeachment managers pointed to the 222-year-old Blount case as an example of the Senate holding an impeachment trial for an official who's no longer in office.

"The Nation's very first impeachment trial concerned an ex-official: Senator William Blount, who had plotted to give the British control over parts of Florida and Louisiana (which were then controlled by Spain and France, respectively)," the impeachment managers wrote in their trial brief last week, pushing back against the Trump team's argument that his trial is unconstitutional because he's now a private citizen.

Blount has some other similarities to the 45th president — he was a businessman from a wealthy family who focused on real estate and struggled with massive debt, and he remained wildly popular with his base despite the impeachment scandal.

While Trump ran on a promise to "make America great again," Blount worked on making America — he was one of the signers of the U.S. Constitution.

"I refer to Blount as our Founding scoundrel," said Stewart Harris, a constitutional law professor at Lincoln Memorial University in Tennessee and a board member of Knoxville's Blount Mansion, Blount's one-time home and a historical landmark.

Blount was born in North Carolina into a "prominent slave-owning family that was very corrupt," and he carried on the family traditions, Harris said.

Blount became an officer in the Revolutionary Army, serving as a paymaster — a position he held in 1780 when "hundreds of thousands of dollars in cash went missing," Harris noted. "He said it went missing in a battle. Maybe it did."

He was later a delegate to the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, where "he wormed his way into the good graces of George Washington" and wrangled an appointment as governor of the Southwest Territory, essentially modern-day Tennessee, Harris said.

Blount successfully pushed for Tennessee to become a state, and was appointed one of its first senators in 1796.

He kept enriching himself by buying massive amounts of land in the state, much of it purchased on credit. Its value plummeted after it appeared the French would take control of Louisiana from Spain and possibly shut down shipping.

That's when Blount hatched his convoluted plan.

According to the Senate historical office, Blount "concocted a scheme for Indians and frontiersmen to attack Spanish Florida and Louisiana, in order to transfer those territories to Great Britain." The plot went awry after one of Blount's rivals got a hold of a letter he'd written to a co-conspirator laying out the plan, and forwarded it to President John Adams.

Adams sent the letter to Congress in July 1797, and both chambers quickly went to work. "It was the first time an official had done something so egregious" in the young country, Harris said.

On July 7, the House voted to impeach Blount for "high crimes and misdemeanors" and on July 8, the Senate voted to expel him.

Blount was ordered to return on July 10 for impeachment proceedings, but fled back to Tennessee.

The Senate created a new position — the sergeant-at-arms — to bring Blount back, but he was unsuccessful.

"Although Blount graciously received the acting Senate sergeant-at-arms at his home, the unrepentant Tennessean's supporters and state authorities warned the official to make no attempt to remove their friend," the Senate Historical Office wrote.

Congress, meanwhile, got tangled in red tape.

The House drafted five articles of impeachment against Blount months after the initial impeachment vote, and his Senate trial didn't begin until December 1798, with Vice President Thomas Jefferson presiding over the proceedings, Senate records show.

"There was a great deal of initial horror," said Gregory Ablavsky, an associate professor of law at Stanford Law School, referring to the charges against Blount, "but then the response got a little lackadaisical."

Blount was a no-show. He stayed in Tennessee, where he'd been elected to the state Senate despite — and in part because of — his expulsion. "Blount's plan was wildly popular among white Tennesseans," and they thought he was being unfairly persecuted by Adams' Federalist party, Ablavsky said.

Blount's lawyers argued the Senate had no jurisdiction over him for two reasons — he'd been a senator, not a "civil officer" of the kind mentioned in the Constitution, and he was no longer in the U.S. Senate.

After three days of arguments, the Senate voted in Blount's favor, finding "this court ought not to hold jurisdiction of the said impeachment, and that the said impeachment is dismissed."

The Senate Historical Office said it "remains unclear on what grounds the Senate based its conclusion as to lack of jurisdiction," but the case "has been interpreted as precedent for determining that a senator cannot be impeached."

The Trump impeachment managers say the finding bolsters their case because the Senate did not explicitly dismiss Blount's "former official" argument.

Chris Magra, a professor of early American history at the University of Tennessee, said, "The impeachment trial was a sort of badge of honor" for Blount at the time in Tennessee. Blount died in 1800 at age 50 after a fever epidemic struck Knoxville.

He's the only U.S. senator to have ever been impeached.