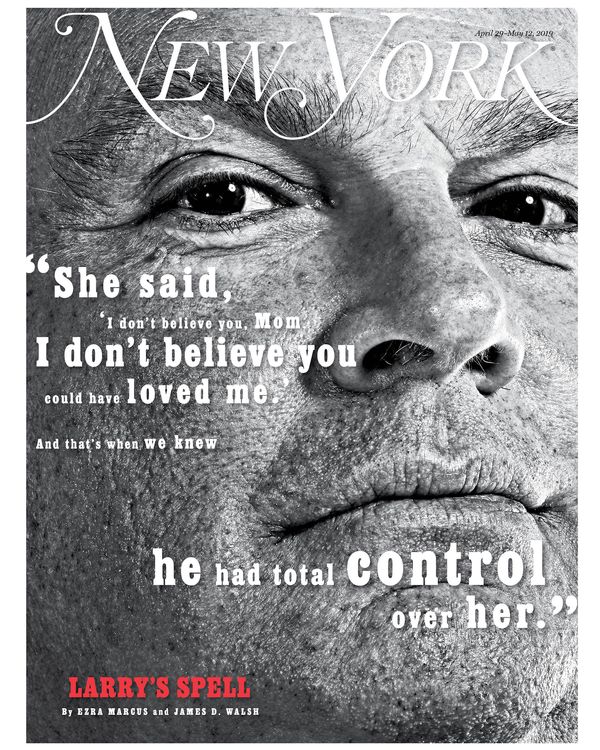

New York Magazine’s April 29–May 12, 2019, issue tells the unsettling story of Larry Ray, who, upon being released from prison in 2010, asked his daughter if he could crash in her Sarah Lawrence dorm. Her roommates and friends soon fell under his control, in thrall to his dark, conspiratorial worldview. Nine years later, they are still struggling to get out from under his grip.

The story began with a tip. In June 2018, co-writer Ezra Marcus, who graduated from Sarah Lawrence in 2014, received word about a website circulating in alumni circles. “I took a look and became immediately convinced that something had gone very wrong,” Marcus says of the site, which alleged Ray had been intentionally poisoned for several years by multiple Sarah Lawrence college students. Ray himself had created the website to bring attention to the supposed conspiracy against him. Marcus began seeking out some of the Sarah Lawrence graduates mentioned on the site and quickly realized that Ray had been living in one of the campus’s dorms. “It became clear that there was a story here,” says Marcus, who then brought his reporting to New York.

To find out what really happened to Ray and the Sarah Lawrence students in his orbit, Marcus and co-writer James D. Walsh, a staff reporter at New York, spoke to over 50 people, including Ray’s victims, their friends, and family members; Ray’s business associates and those who knew him over the decades; and, eventually, Ray himself.

“Larry Ray is someone who has a long paper trail,” says Walsh of the process of verifying the events described in the article. “He has spent a lot of time in courtrooms, appearing as both a party to cases and as a witness.” Walsh and Marcus acquired, among other primary-source material, FBI documents; a psychological evaluation conducted during Ray’s 2005 custody proceeding (which characterized him as “literally impossible to evaluate” because “he is able to manipulate and control almost any situation in which he finds himself”); and hours of testimony from a 2015 housing trial, in which many of the story’s primary characters laid out the alleged conspiracy theory against him. Ray himself also provided documents that he believed supported his recounting of events. Walsh and Marcus also found Ray’s methodical record-keeping useful. “Larry was obsessed with documentation,” says Walsh. All of his devotees wrote exhaustive “confession” letters, some of which are quoted in the article, that, while implausible, were useful tools for corroborating facts, dates, and a timeline.

“Anyone who has ever met Larry has something to say about him,” says Walsh about the reporting process. “Pretty much every person we called or visited exhibited some kind of strong reaction when we said we wanted to ask them about Larry Ray. Some laughed. Others shuddered.”

The primary concern in reporting the piece was the safety of its subjects and sources. Additionally, because the article concerns individuals who have and may still be undergoing traumatic experiences, we solicited guidance from various ethicists and experts in reporting on trauma; New York is grateful for their assistance.

For more in-depth reporting like this, subscribe to New York Magazine.