Archaeologists say they have uncovered a first-century mansion on Jerusalem's Mount Zion, complete with an ancient bathtub that just might have belonged to one of the priests who condemned Jesus to death.

"Byzantine tradition places in our general area the mansion of the high priest Caiaphas or perhaps Annas, who was his father-in-law," Shimon Gibson, the archaeologist co-directing the excavation, said in a news release. "In those days you had extended families who would have been using the same building complex, which might have had up to 20 rooms and several different floors."

The mansion's location and its fancy features are the main lines of evidence for surmising that a member of the priestly class lived there, according to Gibson and the dig's other co-director, James Tabor, a scholar of early Christian history at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. UNC Charlotte has been licensed by Israeli authorities to conduct the Mount Zion excavation.

"We might be digging in the home of one of Jesus' archenemies," Tabor told NBC News. "Someone who was at the trial of Jesus, and probably voted no."

So which was it: Pharisees or Sadducees? "We think Sadducees," Tabor said. "That's the class that has the wealth and more of the control of the temple, and they're in with the Romans."

Bathtub provides a clue

The mansion was built close to the walls of the Second Temple, erected by King Herod the Great in biblical times. It boasted a three-pit oven — a luxury in those days — as well as a private walk-in ritual pool and a separate bathroom.

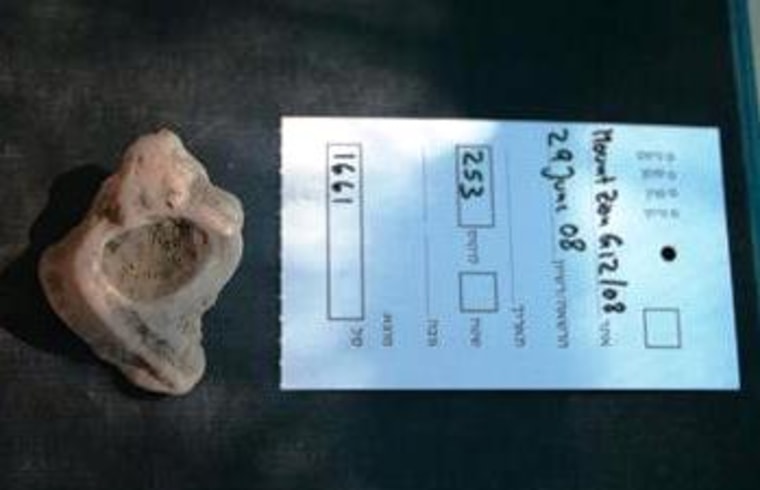

The bathtub is one of the most significant clues in the mystery surrounding the mansion's owners. Only three other such tubs have been linked to the Second Temple period in Israel, Gibson said. Two of them were unearthed in Herod's palaces at Jericho and Masada, and the third was found in a priestly residence excavated nearby in Jerusalem's Jewish Quarter.

"It is only a stone's throw away, and I wouldn't hesitate to say that the people who made that bathroom probably were the same ones who made this one," Gibson said. "It's almost identical, not only in the way it's made, but also in the finishing touches, like the edge of the bath itself."

The excavators said they found a huge number of Murex sea snail shells amid the ruins. Some species of Murex sea snails were highly valued because a blue dye could be extracted from the creatures. In fact, historians say such a dye was specified in Jewish texts as the coloring agent for religious garments.

It's not exactly clear why so many shells were kept in the mansion, but Gibson hypothesizes that they may have been used to identify different grades of dye, since the quality of the product can vary from species to species.

The team also explored a 30-foot-deep (10-meter-deep) cistern. "When we started clearing it, we found a lot of debris inside, which included substantial numbers of animal bones, and then right at the bottom we came across a number of vessels which seemed to be sitting on the floor — cooking pots and bits of an oven as well," Gibson said.

He and his colleagues suggest that Jewish residents might have lived in the cistern as their final refuge during the Roman siege that led to the city's destruction in the year 70. In his account of the siege, the Roman-Jewish historian Josephus said more than 2,000 bodies were found underground in Jerusalem's cisterns and water systems, most of them dead from starvation.

Why the mansion was preserved

The mansion's location, and the timing of its demise, may have been played a role in its preservation: After the Romans pillaged Jerusalem, the area was deserted for 65 years. And when the Roman emperor Hadrian rebuilt the city in 135, the Mount Zion area was left unoccupied. "The ruined field of first-century houses in our area remained there intact up until the beginning of the Byzantine period," in the early 4th century, Gibson said.

Jerusalem's Byzantine inhabitants simply built on top of the older walls. Two centuries later, the ruins were covered with landfill material that was dumped on it from above during the reign of Justinian I, due to the construction of a church complex known as the Nea Ekklesia of the Theotokos just to the northeast.

"The area got submerged," Gibson explained in the news release. "The early Byzantine reconstruction of these two-story Early Roman houses then got buried under rubble and soil fills. Then they established buildings above it. That's why we found an unusually well-preserved set of stratigraphic levels."

This year's Mount Zion excavations were conducted between June 16 and July 11, and the project is slated to continue in 2014 and 2015.

More about biblical archaeology:

- Was Jesus here? Biblical-era town found in Galilee

- Gallery: The archaeology of Christianity

- NBC News archive on biblical archaeology

Alan Boyle is NBCNews.com's science editor. Connect with the Cosmic Log community by "liking" the NBC News Science Facebook page, following @b0yle on Twitter and adding +Alan Boyle to your Google+ circles. To keep up with NBCNews.com's stories about science and space, sign up for the Tech & Science newsletter, delivered to your email in-box every weekday. You can also check out "The Case for Pluto," my book about the controversial dwarf planet and the search for new worlds.