In 2008, web-comic artist Tim Buckley sat down to write a dramatic four-panel strip for his long-running comic “Ctrl+Alt+Del.” What he ended up creating was loss.jpg, the web’s best-known and longest-running meme about a miscarriage.

“I’m not sure what I anticipated, to be honest. I knew it was going to cause some ripples, and it was going to be a busy email day, but honestly by the time that specific comic went live, it was a decision that I had been living with for over a year,” Buckley told me when when I asked him about it this week.

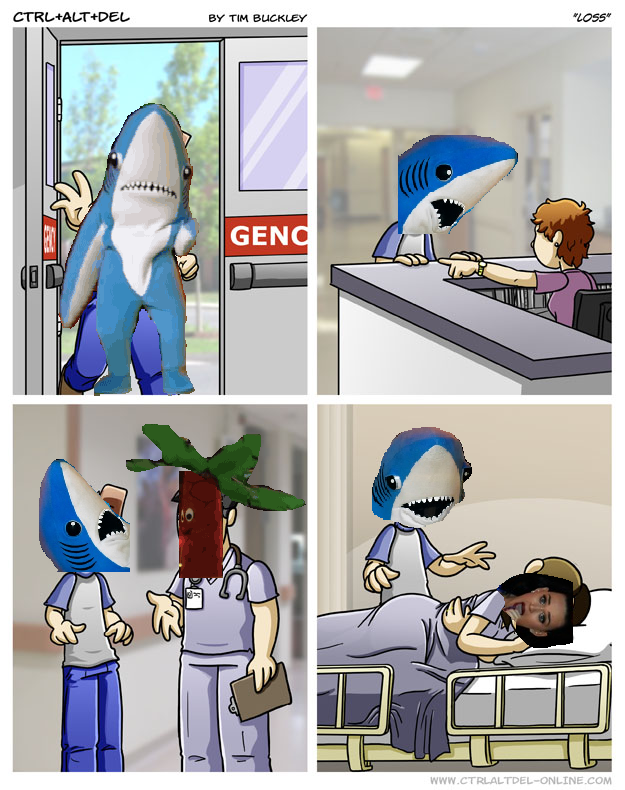

“Loss” is a 4-panel comic strip, completely without dialogue. In the first panel, series protagonist Ethan bursts through the doors of an emergency room. In the second, he worriedly talks to a receptionist, who points him in a certain direction. The third panel shows Ethan conversing with a doctor who is clearly conveying bad news. In the fourth, Ethan stands over his crying fiancée, Lilah, who lies on her side in a hospital bed.

Even if you have never seen the original comic, and wouldn’t recognize the reference, you have likely come across one of its many memetic descendants online. It has been transformed into riffs on The Three Stooges, “Spy Vs. Spy,” a tragic episode of Futurama, and Pokémon. Originally bandied about as the ne plus ultra of stilted web-comic mawkishness, it has since become a meme in its own right — a visual framework atop which message boarders and bloggers can rework references and jokes. Seven years after Buckley attempted to dramatize the lives of his comic characters, members of 4chan’s /v/ board and Tumblr users are using Lilah’s miscarriage as a source of comedy.

To understand where loss.jpg comes from, you need to understand “Ctrl+Alt+Del” (henceforth referred to as “CAD”). Gaming web comics hit their stride in the mid-2000s with “Penny Arcade,” a strip that centers on two misanthropic hard-core gamers. It was followed, unsurprisingly, by other web comics about misanthropic hard-core gamers, including “CAD.” It was a perfect marriage of content and distribution: easily shareable comic strips for gamers, distributed on a medium where they were early adopters. The subgenre was so pervasive that blogs like Joystiq and Kotaku began running weekly roundups.

If “Penny Arcade” represented the high-water mark of the genre (a more-than-debatable assertion) then “CAD” represented the dozens of lesser imitators. “CAD,” like “Penny Arcade,” follows a small cast of main characters — Ethan, Lucas, Lilah, and Zeke (a humanoid robot made from an Xbox) — as they sit on the couch and joke about video games. It alternated between multi-strip story arcs and one-off gags.

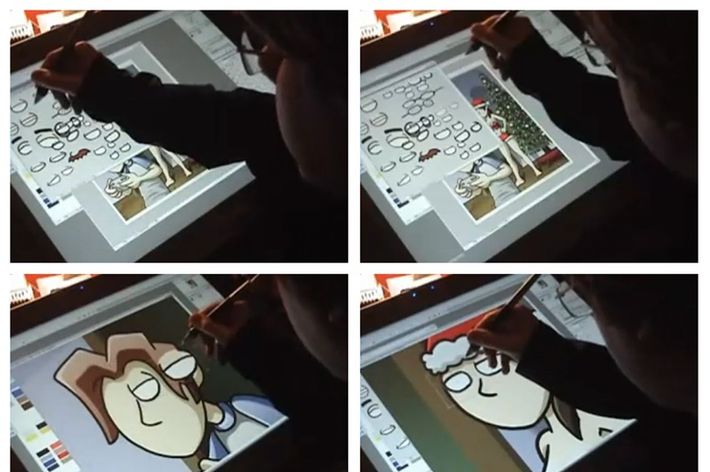

While “CAD” has a large fan base, it has a lot of vocal detractors as well. Critics of “CAD” like to point out the laziness of Tim Buckley’s art style. His characters are rarely expressive, their eyelids all droop and their jaws are all slack. Analysis on the Bad Webcomics Wiki points out that many character expressions are composed of pre-drawn assets, the way you might construct a Bitmoji.

According to a statistical breakdown on Something Awful of more than 1,600 “CAD” comics, 94.44 percent of comics inspected feature what is known as B^U (tilt your head left; it’s an emoticon version of the signature Buckley face) — half-closed eyelids and half-open mouths. (The fact that there was even a statistical breakdown being done should indicate the scale of criticism that “CAD” faced.) In addition, character dialogue is often excessive: Buckley tends to tell, not show.

What I’m trying to say is, well before the publication of “Loss,” “CAD” faced considerable criticism. The comic could be amusing at best and puerile at worst, resorting to violence as a punch line with noticeable frequency. By taking a turn into the gravely serious world of reproductive trauma with “Loss,” Buckley blindsided readers. It was like Carrot Top remade Sophie’s Choice. The last strip to mention Lilah’s pregnancy prior to “Loss” had been published 10 installments and nearly a month prior, and readers found the sudden attempt at gravity hilarious. So they did what the internet does: turned “Loss” — again, a comic strip about miscarriage — into a running joke. One that still continues to this day.

For instance, here is a “Loss” edit from earlier this year. (Like most memes, the vast majority of “Loss” edits are topical, but it gets much weirder.)

If it’s weird to you that people on the internet would take a story about a miscarriage (even a mawkish fictional one) and turn it into a joke, you likely haven’t spent much time online. Buckley knew that readers would have a strong reaction to the piece, and alongside “Loss” he published a preemptive blog post. In it, he explained that he had planned out this narrative development years in advance. He also cited personal experience: an unplanned pregnancy and subsequent miscarriage that broke him out of a “toxic” relationship that he had been in in college. He drew on that experience for the comic.

For the most part, the internet didn’t care. The edits began immediately. On 4chan’s video-games board, /v/, moderators started to ban people who started new threads with them. Even Buckley seemed reluctant to commit to the seriousness of the subject matter. Assuring worried readers that he would not be turning the comic into a drama, he told them: “Nothing dictates that I now need to follow Ethan and Lilah through every second of their sad emotions, putting us right in the middle of it where, yes, it would be a bit depressing.” He weighed the idea of returning to Ethan and Lilah “post-ground-zero, when the pain isn’t so fresh, to show how they handle it.”

If that sounds like hedging, Buckley now admits that it could be. “I think maybe I went into the story line with solid intentions, and solid idea of where I wanted to take it,” he told me, “but perhaps didn’t commit as thoroughly as I should have in practice.” He also notes that, in retrospect, the strong reactions to the piece, supportive or critical, “may have also ended up tempering the final product more than originally intended.”

The other criticism leveled at the strip is that it suffers from a comic-book trope known as “fridging,” in which an author traumatizes a female character in order to spur character development in their male partner. Buckley says that he told the story from Ethan’s viewpoint because that was the only reference he had. “I think I was both afraid of miscalculating a woman’s perspective on that particular subject,” he recalled, “and not confident enough in my dramatic writing abilities to do it justice.” He said that if the situation were to come up again today, he would do more research into how miscarriage affects expectant mothers.

Despite all of these shenanigans, Buckley said that he doesn’t regret having published the comic. He recalled experiences at conventions where females readers said that the story line had helped them. “Miscarriages aren’t something that typically receive a lot of open discussion, and it can be a very isolating experience,” he explained. “And that was really powerful to hear, this idea that no matter what else came out of that story line, there were people it resonated with on a very personal level.”

As for the memes? Buckley’s reaction to them has varied over the years, from anger “because perhaps I had miscalculated my demographic’s ability/willingness to approach such a sensitive subject matter” to frustration for “CAD” being pigeonholed as wacky gamer comic. And on very rare occasions, “As much as I hate to admit it because I certainly don’t want to make light of the subject matter itself, I found them quite amusing.” Now he says that he’s flattered that something he made has been entertaining people for more than seven years.

Why “Loss” has stuck around all these years is not entirely clear. Even the greatest scholars of memes struggle to understand why one particular image or idea circulates and another doesn’t. “Loss” is particularly interesting because it’s difficult to imagine a meme about miscarriage, created from gamer-centric media, becoming popular in 2015. Buckley thinks the meme has taken on a life of its own, divorced from its original context: “Most likely they’re just doing it to have fun, and I certainly wouldn’t suggest that it should stop if they still find amusement in it.”

It’s possible that most “Loss” edits are all in good fun, but that doesn’t change the fact that there is something very odd — probably even wrong — about finding amusement in intimate tragedy. But the gap between intention and effect is an eternal wellspring for humor online, and Buckley’s attempts to reach the heights of pathos with the limited tool set at his disposal revealed a very wide gulf. It wasn’t just that a joke about a miscarriage was an easy way for 4chan’s gleeful meme artists to shock people — it was that the strip was so stilted and unaffecting that no one seemed to be able to take it seriously enough to be shocked.

Memes are frameworks; they’re skeletons. They often contain jokes, but they are not, in and of themselves, funny. They provide a template onto which an infinite number of punch lines and observations can be written. Their uniformity makes them appealing, because they inherently give preference to those who are in the know; those who can identify the meme when others cannot. You have to know about the aforementioned history of “Loss” in order to get the joke. If you don’t, the remixes make little or no sense. In short, “Loss” only has the potential to be funny if you know that it is a callback to expectant parents losing their unborn child.

Eventually, people — mostly residents of 4chan’s /v/ video-game section — moved on from remixing Loss.jpg and started re-creating it in minimalist or abstract form. Its four-panel layout reveals a formula of sorts when broken down to its basic elements.

- Panel one: a straight vertical line.

- Panel two: two straight vertical lines, the one on the right slightly lower than the one on the left.

- Panel three: two even vertical lines.

- Panel four: a vertical line and a horizontal line.

It’s minimalism as comedy. Using this simple recipe, Loss.jpg turned into a sort of test: If you looked at an image and were able to see the comic strip hidden inside, then you were part of an exclusive club (of people who spend too much time online and are laughing about, indirectly at least, a miscarriage).