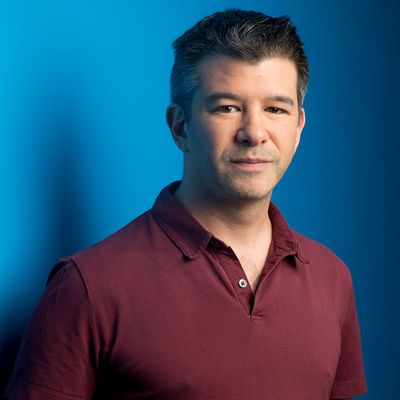

Last month, over drinks with one of the many former Democratic operatives who gave up politics in recent years to help Uber build an empire, I posed a question. Which dethroning will happen first: Donald Trump’s or Travis Kalanick’s? Trump had just fired James Comey, and divulged confidential information to Russia’s foreign minister. Kalanick’s company was being investigated by not only the current Department of Justice, which was looking into whether it deceived government regulators and law enforcement, but also by former Attorney General Eric Holder, whose law firm was finishing up an investigation into the company’s noxious internal culture. The former politico immediately answered, as half a dozen others did, that it seemed more likely that 20 Republican senators would turn on Trump, than that anyone could force Kalanick from his entrenched position at the company he built. “The only thing that will remove Travis is something criminal, or some real financial pressure,” one former senior employee told me.

Barring news from the DOJ, it seems the latter has come to bear. Yesterday, five of Uber’s major investors, who control around 40 percent of the company’s stock, sent Kalanick a letter insisting that he resign. The insistence not only on his resignation, but the immediate hiring of an experienced CFO, suggests the investors are suddenly worried that Kalanick was hurting rather than helping his own company’s financial prospects, and that its long-promised IPO was in danger. After “hours of drama,” as the Times put it, Kalanick stepped down, just a week after announcing that he would be taking a leave of absence. “I love Uber more than anything in the world,” Kalanick said in a statement, before adding that he was stepping down “so that Uber can go back to building rather than be distracted with another fight.” This probably goes without saying, but people within Uber are “shocked,” according to one employee.

Kalanick is identified with Uber in the way that Mark Zuckerberg is identified with Facebook, but his primary contribution to the company’s early days was to convince his co-founder, Garrett Camp, who came up with the idea and the name, that Uber should simply become a network for drivers who already had cars, rather than a fleet-owning business itself. That was a good idea, but not a new one — a company called Taxi Magic was already deploying existing drivers in San Francisco via smartphone app — and throughout Kalanick’s tenure, Uber has been much better at ruthless implementation than it has been at innovation. Lyft was already allowing regular users to pick up passengers in their Honda Civics when Uber was still exclusively using professional drivers. Google was working on self-driving cars for half a decade before Kalanick decided to build an autonomous program of his own.

Like most any rocket ship of a company, Uber rose on the back of a variety of forces — the invention of the iPhone, a surfeit of people looking for temporary work during the recession, seemingly limitless venture capital — that had nothing to do with the ingenuity of the people running it. While even Kalanick’s critics consider him extremely intelligent, and incredibly hardworking, what Kalanick primarily brought was a seemingly messianic belief in the rightness of his cause and the deplorability of his enemies, as well as a willingness to do whatever it took to win and a lack of concern for what the haters think about him. While the #DeleteUber saga tied Kalanick to Trump in many minds, Kalanick was never as Trumpian, at least politically, as many of his recent detractors wanted to paint him to be. (He stoutly objected to the immigration ban, and until Elon Musk dropped out over Trump’s rejection of the Paris accord, Kalanick was the only person to resign from the president’s technology council, leaving Tim Cook and Jeff Bezos to sit next to Trump at the council’s meeting on Monday, doing their best to look defiant in front of the cameras.) If there was a way Kalanick resembled Trump, it was the fact that he may have been built more for running the campaign than the office. In 2014, Kalanick even started referring to Uber as a campaign; his opponent wasn’t “Crooked Hillary,” it was “an asshole named Taxi” — an alternative that wasn’t perfect, but was never nearly as bad as he made it out to be. Kalanick didn’t love a stage the way Trump does — he is the only person I’ve ever seen give a Ted Talk with notes in his hand — but he loved a good fight.

The challenges of running a company on the verge of maturity are very different, and Kalanick was often slow, or unwilling, to adjust his thinking to his company’s new reality. (Its an odd coincidence, or not, that on the day Kalanick resigned, Uber announced it would begin allowing riders to tip, an idea Kalanick had devoutly opposed.) Uber still doesn’t own cars, but it does lease them to drivers — through a scheme that the Federal Trade Commission determined was misleading. Half of the company’s skyrocketing revenue comes from people who drive full time, but it remains insistent on denying them even the most basic protections afforded to full-time workers at any other company. When you suddenly employ thousands, none of whom are as invested in the company’s success as you (literally or figuratively), a leader’s concerns have to expand. Uber did not have a human-resources department until it had grown to some 500 employees, which left Kalanick to send out an email to what was then a company of 400 employees, warning them not to have sex with each other.

There is also the fact that what started out as a way to get to and from a party in style has grown into an effort to change modern transportation as we know it. Several people who worked at Uber during various parts of the company’s rise told me that its ever-expanding mission took many people by surprise. Kalanick hadn’t set out to change the world, but once the size and valuation of his company demanded that, it was never quite clear whether he had much interest in doing so responsibly. And while founders like Zuckerberg, or Sergey Brin and Larry Page of Google, were able to recruit and retain experienced corporate executives to manage their suddenly enormous companies, Kalanick was consistently unable, or unwilling, to share the challenges of leadership: Jeff Jones, who was hired as Uber’s president in 2016, left the company after six months.

Uber without Kalanick may well be more stable, though the company has lost eight top executives this year alone and faces considerable challenges — it continues to lose shocking amounts of money, and is facing a potentially devastating lawsuit brought by Waymo, Google’s self-driving-car outfit, alleging that Uber stole its technology — even without Kalanick at the helm. Kalanick without Uber is a different matter. Kalanick has had an extremely difficult month: His mother was killed in a boating accident, he became a household name for all the wrong reasons, and he has now been booted from the thing to which he devoted nearly a decade of his life.

Even before he was fired, one person close to Kalanick told me that he worried about Kalanick’s post-Uber life. “He has no other interests — no interest, from what I can tell, in philanthropy — and he is going to go through a massive personal crisis,” the person said. In a moment of magnanimity, Bill Gurley, one of the investors who pushed Kalanick to resign, wrote on Twitter, “There will be many pages in the history books devoted to [Kalanick] — very few entrepreneurs have had such a lasting impact on the world.”

Whether Kalanick is done writing his chapters is unclear. He remains on Uber’s board, with the single largest voting share, and the prospect of running a company while Kalanick looms in the boardroom, possibly angling to make a Jobs-ian return to the company he founded, cannot be an enticing prospect to the most qualified CEO candidates.

But whatever the books end up saying, they will be written about a company that is wildly different than the one Kalanick helped start. It employs 12,000 people, and the decisions it makes, buoyed by the money it spends, have already warped the tech world, transportation systems, and our cities in general in ways that we are only beginning to understand. Whether or not Uber has been and will be a force for good, or bad, or just an interesting blip, remains to be seen. But for the moment, and for the first time, that question is out of Travis Kalanick’s hands.