U.S. news

Photos: A West Virginia town was beating back addiction crisis. Then came Covid.

As the pandemic killed more than a half-million Americans, it also quietly inflamed another public health crisis: addiction.

Larrecsa Cox peers around a stairwell while walking through an abandoned home in Huntington, W.Va., on March 18.

Cox leads a team whose mission is to find every overdose survivor to save them from the next one.

Huntington was once ground zero for the addiction epidemic, and several years ago they formed the Quick Response Team. It was a hard-fought battle, but it worked. The county’s overdose rate plummeted.

Then the pandemic arrived and it undid much of their effort.

Cox demonstrates how to administer the overdose reversal medication naloxone in Branchland on March 15.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that more than 88,000 people died of drug overdoses in the 12 months ending in August 2020 — the latest figures available. That is the highest number of overdose deaths ever recorded in a year.

“People I’ve known all my life since I was born, it takes both hands to count them,” she said. “In the last six months, they’re gone.”

Yvonne Ash's son Steven, 33, working at the tire shop on March 17 where he overdosed just days before in Huntington.

When Ash overdosed, he slumped among the piles of used tires behind the shop his family has owned for generations. His mother, pleading, crying, had thrown water on him because she couldn’t think of anything else to do.

Cox has a calm demeanor, with dreadlocks down to her waist.

“You’re not in trouble,” she always says first, then offers them naloxone.

She wants her clients to be straight with her so she’s straight with them. “Everybody here is thinking that you’re going to go get high and not come back,” she’ll say, their weeping families nodding their heads.

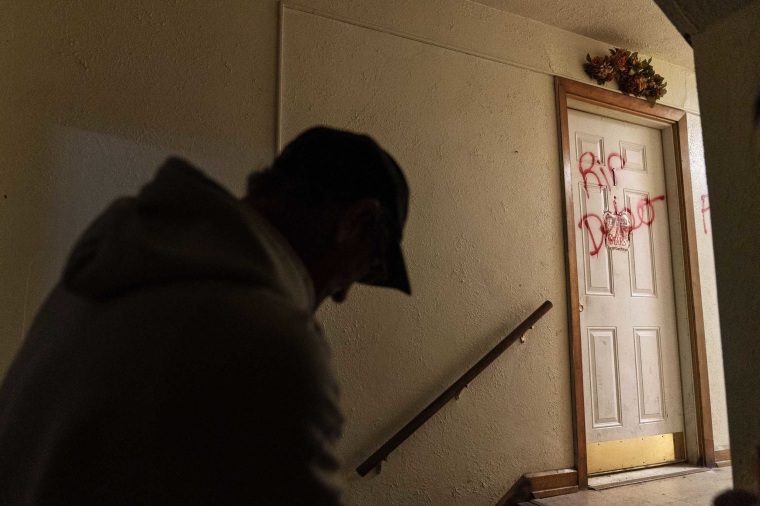

The message "RIP Debo" is spray-painted on the apartment door that had been the home of 41-year-old Debbie Barnette, a mother of three, in Huntington.

Barnette had struggled with addiction all her life. She overdosed many times and developed infections. By the time she sought treatment, the infection in her heart was too far gone.

Sue Howland, a member of the Quick Response Team, checks in on Betty Thompson, 65, who struggles with alcohol addiction, at her apartment in Huntington.

It had been days since Thompson had eaten or taken her medications. Cox combed through her bottles of pills and sorted them into a pill organizer. They scheduled an appointment with her doctor the next day. They called to have a sandwich delivered. Cox packed up her trash to haul out to the dumpster.

A banner with an image of Jesus hangs outside a home as a mail carrier walks down the street in Huntington on March 17.

The Quick Response Team was born amid a horrific crescendo of America’s addiction epidemic: On the afternoon of Aug. 15, 2016, in just four hours, 28 people overdosed in Huntington. By 2017, the county had an average of six overdoses a day. Paramedics grew weary of reviving the same people again and again.

Jeff and Lola Carter stand with their daughter, Amanda, and a framed photo of Kayla, their daughter who struggled with drug addiction, at their home in Milton.

Kayla Carter was hospitalized last summer with endocarditis, a heart infection from using dirty needles. Her parents stood at her bedside and thought she looked 100 years old. She stayed off drugs when she got out of the hospital. She said she was sorry for all she’d missed: babies born, birthday parties, funerals. They thought they had her back.

Then she stopped answering calls. Her mother went to her apartment on a Friday morning in October and found her dead on her bathroom floor.

A police patrol vehicle sits along a stretch of railroad tracks in Huntington on March 17.

Huntington was once a thriving industrial town of almost 100,000 people. It sits at the corner of West Virginia, Kentucky and Ohio, and the railroad tracks through town used to rumble all day from trains packed with coal. Then the coal industry collapsed, and the trains don't come so much anymore.

Cox talks with paramedics at an overdose call in Huntington.

This beleaguered city offered a glimmer of hope to a nation impotent to contain its decades-long addiction catastrophe. The federal government honored Huntington as a model city. They won awards. Other places came to study their success.

The first couple months of the pandemic were quiet. Then came May. The 911 calls started and seemed like they wouldn’t stop — 142 in a single month, nearly as many as in the worst of their crisis.

Sue Howland, left, and Sarah Kelly hug after Howland presented her with a coin marking Kelly's one-year anniversary in recovery, outside her home in Guyandotte on March 17.

After struggling with opioid addiction most of her life, 37-year-old Sarah Kelly white-knuckled her way through the pandemic. Then she navigated courts to get custody of her kids back after more than two years apart.

“I knew there was this version of me still in there somewhere, and I knew that if I woke up every day and really decided to stay sober, I could get to be her again,” Kelly said. “I could look in the mirror and be proud of who I was, and my children could be proud of me.”

They live together now in a little house on the outskirts of town.

-- Reporting by Claire Galofaro / AP