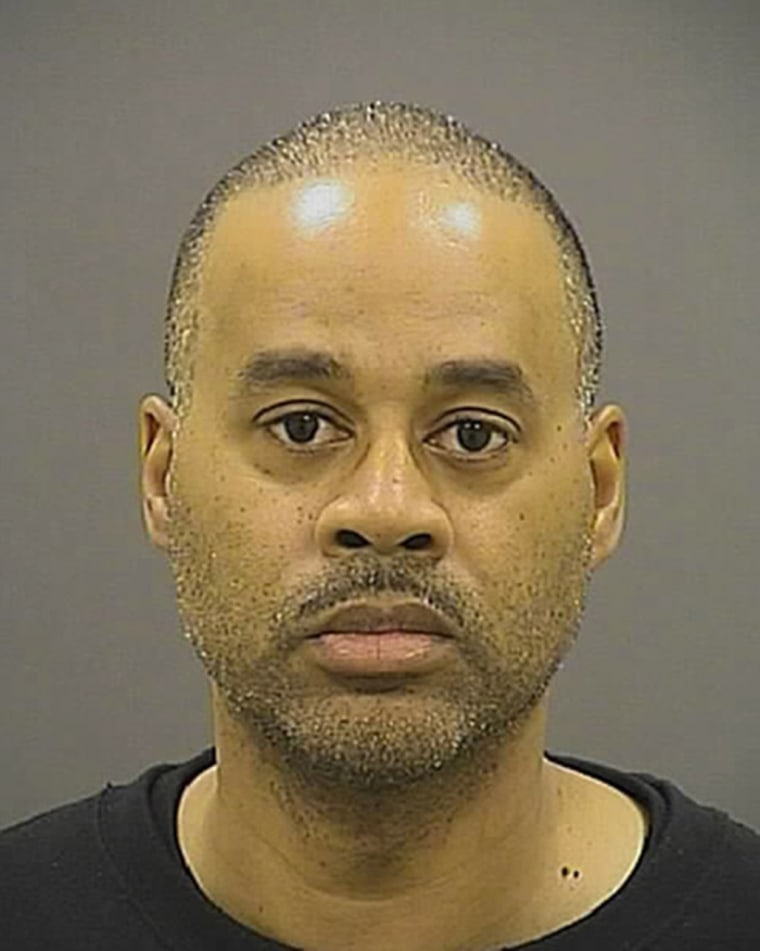

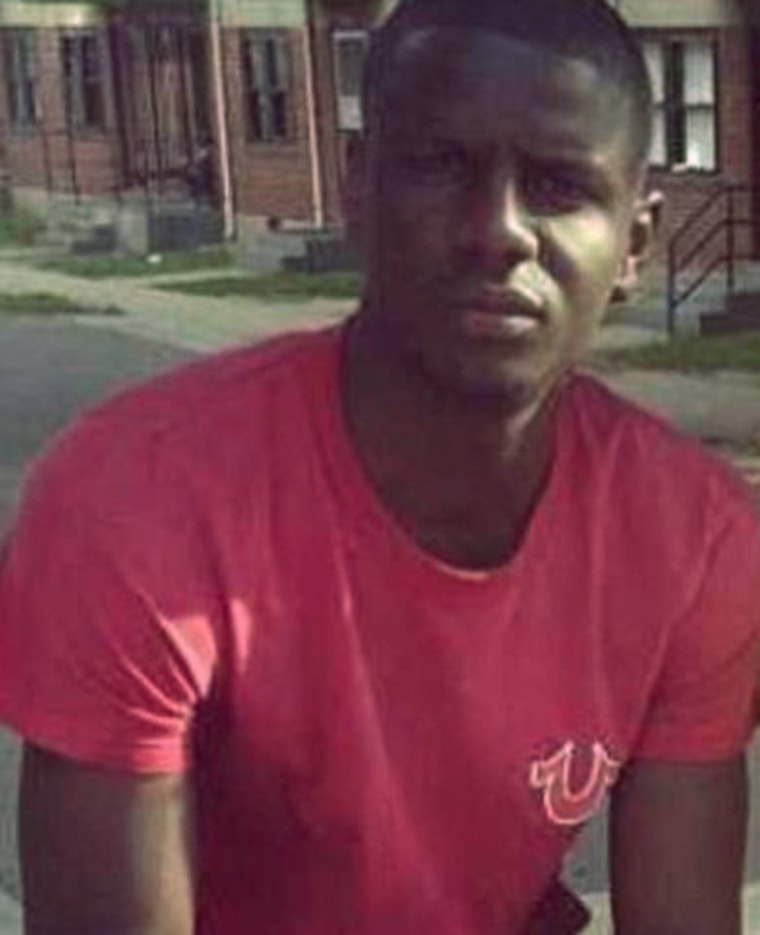

The Baltimore prosecutor’s office on Thursday is beginning its highest profile and most pivotal case in the six Freddie Gray trials — the effort to convict Officer Caesar Goodson of "depraved-heart" murder.

And in data exclusively obtained by NBC News, a conviction for Goodson would be the first of its kind in at least a decade.

Failure to net a conviction for Goodson, who was driving the police van when Gray sustained ultimately fatal spinal injuries, could spell an end to Baltimore City State’s Marilyn Mosby's high-stakes legal gambit to send a message on combating police brutality.

"She has a tremendous amount on the line, her entire career, particularly her credibility," said former Maryland prosecutor Rene Sandler. "She should take a strong look at the other cases, if there is another acquittal."

The odds are against her.

Goodson's defense team saw a more promising legal strategy in opting for a bench trial on Monday, which some legal experts say should affect the prosecution’s counter-strategy.

In a jury trial, the prosecution presents evidence to 12 members of a jury. Twelve different people work in tandem to return a verdict. In a bench trial, that job is put in the hands of one individual, the judge.

Related: Caesar Goodson, Van Driver in Freddie Gray Case, Opts for Bench Trial

In data compiled for NBC News by Bowling Green State University criminologist Philip Stinson, who studies officer arrests, between 2005-2011, not a single officer was convicted by a judge during a bench trial for murder or manslaughter in the line of duty.

"Goodson would be the first in at least a dozen years," Stinson said.

According to research by Stinson, 23 officers have been convicted of murder or manslaughter for shootings in the line of duty since 2005. During that time period, there were 6,724 officer arrests for a variety of on-duty crimes.

Legal experts say the weaknesses in the prosecution's approach are becoming increasingly apparent.

Related: Officer Charged in Freddie Gray Case, Edward Nero, Not Guilty on All Counts

Prosecutors failed to obtain a guilty verdict in the previous trials of Officer William Porter, which ended in a mistrial in December, and Edward Nero, who opted for a bench trial and was acquitted last month.

Last year, Mosby charged six officers in connection with Gray's death.

At the time, Mosby's move was hailed by some as refreshingly aggressive and criticized by others as hasty and reactionary.

“They came out swinging strong, too fast, revealing information in the beginning that may or may not have been supported in discovery. That’s dangerous to do,” said Sandler, the former prosecutor.

The state over-dealt its hand, she said. Now prosecutors are going through the “fact by fact analysis of each officer” which isn't holding up the way they anticipated.

Either the “evidence they had wasn't as strong as they originally thought, or the strong evidence they have can’t be presented,” said Renee Hutchins, a professor at Maryland Carey School of Law.

For example, the prosecution was dealt a blow on Monday when Circuit Judge Barry G. Williams ruled that Porter’s alleged statement to Detective Syreeta Teel that he heard Gray say “I can’t breathe” is not allowed in evidence.

Prosecutors have also yet to make a strong case to show a link between the officers' actions and outcome under legal standards, Sandler said, adding “that is difficult to prove.”

Add to the prosecution's challenges the fact that Williams, who will preside over Goodson's trial, is the same judge who declared a mistrial in the Porter case and issued an acquittal in the Nero case.

Police defendants are unique in that judges and juries tend not to convict, said Paul Butler, a professor at Georgetown School of Law.

Emotion can often play a big factor for juries said Baltimore area criminal defense attorney Warren Brown. But prosecutors in the Goodson case “now know that they can’t seize upon the emotions of jury,” he said.

In the days following Gray’s death, riots and violent protests broke out in Baltimore. Public opinion towards law enforcement plunged and the city's minority communities demanded justice.

This was one of the reasons why Mosby responded so strongly and swiftly in announcing charges, said former Baltimore prosecutor Ahmet Hisim.

"It seemed like the decision was more for the appeasement of the community and now they (prosecutors) are thinking 'do we really have the evidence to prove this,' that's where they are at now," he said.

Goodson faces second-degree "depraved heart" murder, manslaughter, assault, reckless endangerment and misconduct in office charges.

Proving "depraved heart murder," which requires proof of that person acted with "callous disregard for the value of human life will be very difficult," according to the Legal Information Institute at Cornell University.

“It will be an uphill battle to convince a judge or a jury," said Douglas Colbert, a University of Maryland law professor adding that the state should focus on looking for other evidence to win. "They should look for evidence that shows Goodson was aware of Freddie Gray’s dangerous health conditions or they should find other officers who were aware of the use of 'rough rides'," he said.

Ultimately, the stakes in the Goodson case are about more than a guilty verdict.

The Goodson case verdict could prove make-or-break when it comes to the pending trials for Officer Garrett E. Miller, Lt. Brian W. Rice, and Sgt. Alicia D. White.

If Goodson isn't convicted, the state might drop charges against the remaining officers slated for court, said David Gray a University of Maryland law professor. Another acquittal would force any rational prosecutor to take a step back and think whether they should expend time and resources to move forward after that, he said.

“A lot is riding on this case," he said. "It has to be their most airtight, they have to throw everything they have into this.”