The U.S. government's main cybersecurity watchdog has spent much of the last four years trying to stop a repeat of the 2016 election. That's meant reaching out to the country's more than 3,000 counties with an offer: free cybersecurity tools.

It's a tough job. Some counties are receptive and engaged. Others barely have enough people to put on their local election work. One of the main services offered — a weekly scan of a county's internet connected networks meant to make sure its voter database is safe — has signed up a little more than 200 counties.

“This is good progress,” Geoff Hale, director of the U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency’s Election Security Initiative, said. “It's not great progress.”

The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency is the nation's primary department tasked with national security related to the internet and technology. With fewer than three months before election day, Hale and the agency are on alert for any signs of foreign election interference. So far, there’s little to suggest Russia or another country is laying the groundwork for a major, sustained hacking campaign, Director Chris Krebs has said.

But that doesn't mean there are not some causes for concern. Despite the agency’s efforts, many counties are still operating without its help. And while there are some concerns about Russia or another foreign adversary repeating the 2016 efforts to interfere in the election, experts are more focused on newer types of attacks such as ransomware — and the possible domino effect that even a couple of small but successful attacks could have on the nation's faith in the election.

A recent poll from NBC and SurveyMonkey found that a majority of Americans doubt the election will be fair, and officials fear that a hack of election related systems, even if it can’t affect vote totals, could seriously damage voter confidence.

“There's a zero tolerance for failure in this community, as a lot of the advantages go to the adversary,” Hale said. “But that's the game we're playing, and that's what election officials understand and why they patch these systems and maintain their security as best they can.”

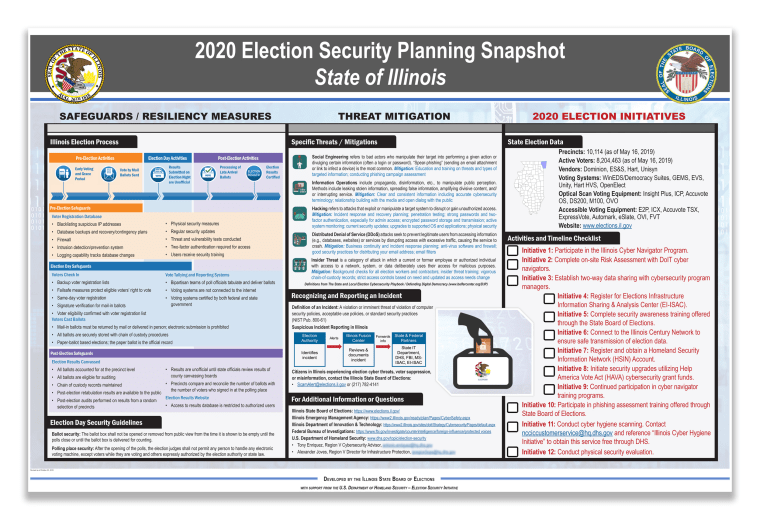

There are bright spots. The agency has signed on 44 state governments for its scanning system, a program it pushed in 2016 after Russian military officers hacked the Illinois voter registration database. More than 5,500 jurisdictions — whether they’re cities, counties, states or precincts — have received a tailored checklist of basic security measures they can take. Eighteen states have conducted phishing assessments for their local officials — a relevant tactic, considering in 2016 Russia sent such emails to at least 120 officials in Florida alone. And about 85 percent of Americans vote somewhere that participates in a network that quickly shares information about potential cyberthreats. But that does leave 15 percent of the country that doesn’t engage.

Orange County, California, is one of the places that has embraced the agency’s efforts.

“It’s been very positive,” Registrar of Voters Neal Kelley said. “My guys are dealing with CISA on an ongoing basis. We’ve had issues pop up where we’ve had attempted intrusions, where our computers had malware exposed to them.”

But with more than 1.6 million voters, and some of the highest per-capita income in the country, the county has resources that others don't.

“Orange County, California, may be more well-funded and have more capability than some states do,” Hale said. “Then you hit the small organizations that they don't fully understand what's on and not on their networks.”

The U.S. election system is incredibly diverse, with states choosing many of their own laws and customs, and local election officials running individual polling places. That makes the idea of a widespread election hack nearly impossible — but it also makes it extraordinarily difficult to get everyone involved in the system on the same page.

Reasons why federal tools aren’t more widely adopted vary, but they largely center around resources, Rita Reynolds, the chief technology officer of the National Association of Counties, said. Even if a cybersecurity tool is free, someone still needs to set it up.

“It’s awareness, it’s staff turnover, it’s priorities based on your physical resources to implement,” she said.

“It may be free, but you still have to implement the tools. We just don‘t have enough technology and security professionals at the county level, because of funding,” she said.

As an example of what could go wrong on Election Day, the agency cites the possibility that a small county could get infected with ransomware, locking up its computers and hampering its ability to submit election results or update its website to direct voters who need polling place updates. Even if the county used provisional ballots for anyone who couldn’t check in and delivered its vote count in person, the perception that the election had been “hacked” could persist.

“The ability of disinformation actors to amplify anything that’s actually out of scale is one of the things we worry about,” Hale said. “They have an asymmetrical advantage.”

State and local governments have been particular victims of ransomware in recent years. There have been at least 177 publicly reported incidents of ransomware infections of state and local government networks since the beginning of 2019, Allan Liska, a ransomware analyst at the cybersecurity firm Recorded Future, said, though the actual number is likely higher.

Ransomware gangs often scan the internet looking for networks that haven’t recently updated their systems. Small government networks make “attractive targets because they garner a lot of press,” he said.

“Whether it is true or not, ransomware threat actors think state and local governments are more likely to pay because of this,” Liska said.

“We've found that some jurisdictions will still dismiss the idea of a nation-state targeting them because they're just a little ole county in a noncompetitive state,” Hale said. “But everybody understands ransomware. They've seen other counties attacked by it.”

Even with the election less than three months away, Hale said, it’s not too late for local election officials to start using government cybersecurity.

“Adversaries are still using whatever's easiest, so the simplest vulnerability is the methods like phishing,” he said. “So, secure the small stuff. We can still turn on our vulnerability scanning. If you sign up today, it takes 24-48 hours to get those going.”