When Twitter banned Donald Trump from its platform this month, the move was the culmination of years of escalations between the company and Trump, its highest-profile power user.

But it also raised some crucial questions: Should one company be able to wield such power? In a country that places outsize value on free speech, was there no legal recourse for one of the most powerful people in the world for being booted from one of the internet's biggest communities?

Simply put: There are few — if any — legal challenges to the power Twitter and other tech companies wield over online speech.

"These companies have become so bold because they're limited shockingly little," said Mark Grady, a professor at the UCLA School of Law who specializes in law and economics. "Every time you think of an angle that might be restrained upon their moderation conduct, it turns out to be a nonstarter. It's really remarkable when you look at the body of law that we've got governing these entities that there's very little that constrains them."

Any attempts to regulate how the major U.S. tech companies moderate their platforms could prove to be difficult within the current U.S. legal framework, legal experts said. The First Amendment protects speech from intrusion by the government, while antitrust law was written to address issues like competition and consumer prices.

The question of what role the government has — or should have — in regulating how tech companies moderate their platforms has emerged as a political flashpoint with little bipartisan agreement.

Facebook, Twitter, Google, Apple, Amazon and many other technology companies heightened the debate in recent weeks when they took significant steps to crack down on extremists after the riot at the Capitol, which left five people dead.

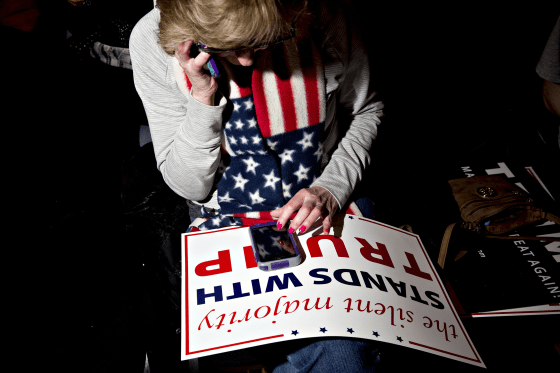

The moves drew backlash from some conservatives and free speech activists, who argued that tech companies were unfairly censoring speech and that their power in the digital realm had grown too great.

And while tech companies face antitrust scrutiny for their size and market power, answers to the question of what the government can do about their control of online speech are vague, at best. That's in part because antitrust laws aren't focused on "the tendency of monopoly to produce less diverse speech," Grady said.

He said that the companies' ability to moderate content isn't limited by the First Amendment and that they can't be held liable for content posted by users because of protections granted by Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act. That regulation has also become a hotly debated topic.

A tenet of existing antitrust law is to protect competition. But while many companies, including Facebook, Google and Amazon, have histories of acquiring competitors that posed challenges to their businesses, the specific market power they exercised with content decisions over the last week is difficult to regulate under that definition.

Aaron Edlin, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley School of Law who specializes in antitrust economics and antitrust law, said regulators would have to prove that the companies conspired to silence voices or platforms when they took nearly simultaneous action.

"If each of them individually reacted to what they saw happen at the Capitol, then it's not so disturbing from an antitrust perspective," he said. "If everyone opens their umbrella when it rains, I don't look at that and say they must be in a conspiracy to open their umbrellas. There's a good reason to open your umbrella when it rains, and there's a good business reason for these firms to have made an individual decision."

The companies' actions over the last week reinforced just how much power they have, but Edlin said power isn't a violation of antitrust law.

And that power only continues to grow as they attract more users and become more popular sources of information, said Sinan Aral, director of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Initiative on the Digital Economy and author of "The Hype Machine."

Aral said antitrust cases are about the "effects of market concentration on consumer harm," but he said the definition of consumer harm is shifting. Traditionally it was focused on price, but a concentration of power can create harm in many other ways, and it needs to be thought of more broadly to include causes like privacy, political polarization and the rise of extremism.

"These are all harms to society, but do I think they're legitimate harms that can be cited in an antitrust case? Do they come and stem solely from market concentration? No," he said. "I believe these are market failures in their own right that deserve their own legislative scrutiny."

Aral said that "antitrust is not a silver bullet" but that it's not as simple as repealing Section 230.

"Obviously we have to be cognizant of the fact that they have undue influence over what information is put out into the world, so we need to think about how we develop the norms and laws around content moderation," he said. "Repeal of Section 230 would not solve anything and would be a detriment to the free internet as we know it."

He said companies would either wash their hands of attempts to moderate content or take such conservative stances that speech would be chilled and private censorship would flourish. Instead, he said, the legislative branch should carefully reform Section 230 and define the boundary between free and harmful speech.

All of the legal experts NBC News spoke with for this article agreed that the major tech companies have incredible influence over the content that's put out into the world. But checking that power is likely to require overhauling existing legislation or enacting new laws, neither of which will happen soon.

CORRECTION (Jan. 21, 2021, 5:40 p.m. ET): A previous version of this article misstated when Twitter banned Donald Trump. It banned him on Jan. 8, not last month.