In 1973, at the college newspaper in Boston where I was editor, we received a promo copy of a new album, “The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle,” by Bruce Springsteen. We never got promo copies. Who was this guy? Although this was his second album on big-time label Columbia, I had never heard of him. None of us had. Except for one of the younger staff members. “I know him from New Jersey,” she said. “He’s gonna be huge.” Yeah, right.

A few months later, in the spring of 1974, my roommate and I were at a small Harvard Square club, Charlie’s Place. Springsteen was playing multiple sets over several nights. He had not yet broken through, but the place was packed. Word was out. By now, after several spins through the record, our household of college roommates had internalized it. The odd, rambling story songs made sense — and now, hearing them live, they made more than sense; they were revelatory. I remember Springsteen and the E Street Band playing most of them that night — “4th of July, Asbury Park (Sandy),” “New York City Serenade,” “Kitty’s Back,” “Rosalita (Come Out Tonight).”

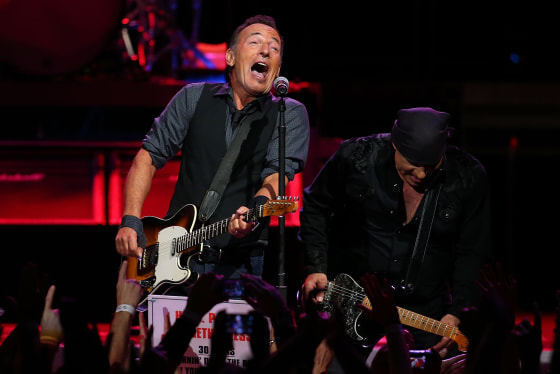

The kind of connection I saw Springseen make that night is something that has sustained him and his career for 45 years, through all kinds of albums of varying success.

It was a galvanizing performance. As I remember it, we stood for the entire set, slightly behind the non-bandstand (there was no riser), transfixed. Yes, the songs all made sense now — their mix of folk, rock, R&B, even a bit of classical (courtesy of then-pianist David Sancious), their structures not randomly discursive but inevitably right. As for the lyrics, other than Dylan (the obvious comparison), who else was doing stuff like this? Character portraits, urban narratives, street-level (or boardwalk-level) observations of the struggles and wonders of everyday life (“Circus town’s on the live wire!”).

But the thing that really made a difference that night — and has marked Springsteen as singular ever since, fueling the anticipation of the release of his new “Western Stars” album on Friday — was the way he connected with us in the audience. It’s a given that a performing artist has to engage with the audience (“Hello, Cleveland!”), but how many artists, before or since, have seemed less than generous onstage. At worst, they seem burdened with the whole job of performing. Even people who play or sing beautifully sometimes seem to offer little more than: “This is what I do. You’re invited to watch.” For others who are more giving with their time and onstage energy, it’s the majesty of their performance that’s the thing (thank you, Freddie Mercury and Bono).

Springsteen that night — skinny, charming, self-effacing, funny — gave more than energy and vocal power and time (though this wasn’t one of those latter-day three-to-four hour shows). His “audience engagement” felt like a personal connection to each of us in the crowd. It was big, and grand, and full-hearted, but it was also intimate.

The kind of connection I saw Springsteen make that night is something that has sustained him and his career for 45 years, through all kinds of albums of varying success. That bond with his audience has contributed to the excitement surrounding “Western Stars,” his first album in five years. Whatever the verdict is on his new songs, it will be informed by decades of forging and staying true to that connection.

About a month after his Charlie’s Place run, Springsteen gave his epochal performances at the Harvard Square Theatre (opening for Bonnie Raitt!). Those were the shows that inspired rock critic and eventual Springsteen manager Jon Landau to write, “I have seen rock and roll future, and it’s name is Bruce Springsteen.”

It wasn’t hard to see what Landau was talking about — pop music is a commodity, but we’re always hoping for something more. Landau’s essay was about more than a good show, it was about spiritual rebirth.

Springsteen was searching, and it was a search he invited his audience to participate in. When he moved on to arenas and stadiums (something he’d sworn he’d never do) the shows became unabashed revival meetings: “Can I get a witness!”

The newer, bigger Springsteen wasn’t for everyone. Even I balked at first at the oversized production and tightly turned hooks of the breakthrough “Born to Run” and some of its lyrical bombast (“Just wrap your legs 'round these velvet rims / And strap your hands across my engine.” Please, no!). When the unlikely dance-rock hit “Born in the USA” was appropriated by the Reagan campaign, some people blamed the songwriting. He’s taken knocks for selling a phony working-class hero routine, and, in the post-punk world, his revival-meeting guilelessness has come across to some as more corny than “authentic.”

But wasn’t Springsteen, with his boardwalk hustlers and corner boys, protopunk after all? At the time, his music seemed of a piece with the mean streets brought to life by Martin Scorsese and Robert De Niro.

And there has always been his ability to make the biggest statements intimate. Springsteen told Rolling Stone magazine that he considered a concert ticket a personal contract, and his painstaking sound checks were legendary. Similarly, his revival meetings were part of a mission. “The church of rock 'n' roll,” he called it. Springsteen has always combined his performer’s need to be heard with the fulfillment of a social need.

Springsteen has made his important statements of social commentary, like “American Skin (41 Shots).” But he was at his most “useful” as a social force when he played in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, performing music from his Pete Seeger tribute album, mining Seeger protest songs as well as a broader strain of Americana including hootenannies, jug bands and early jazz and blues to convey a spirit of community and solidarity in a ravaged city abandoned by its government. Another cathartic revival meeting.

He was the true modern troubadour — with all his fame and worldly experience, still going from town to town, gathering stories.

It had been a little over a decade since the release of “The Ghost of Tom Joad,” another protest album in its way. In a show at the Orpheum Theatre in Boston, Springsteen, alone with his guitar, played one song after another and described how he made them — taking off in the night from L.A. on his motorcycle, checking in at truck stops and coffee shops.

It occurred to me then that he was the true modern troubadour — with all his fame and worldly experience, still going from town to town, gathering stories. “Thanks for giving me the space to do this,” he told the audience at the Orpheum, grateful not to be interrupted by whoops and shouted requests. And it reminded me of the intimacy of that first big show at Charlie’s. The intimate connection, the shared search — that has made him essential to so many for so long.