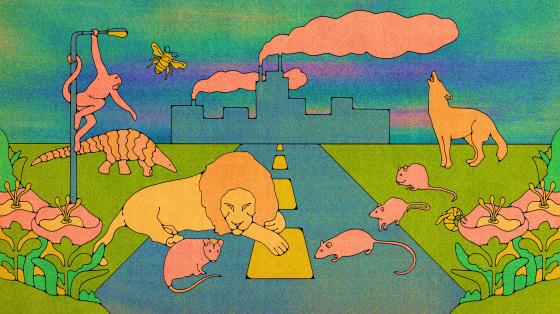

Coyotes howling in San Francisco. Mountain lions roaming Chile's capital city. And in South Africa, a pride of lions relaxing on a golf course and penguins strolling through empty streets.

These scenes might seem straight out of The Far Side, but they are part of the “new normal” where the rules have changed for man and beast alike. With animals stretching their legs and exploring the wider human world, it might seem like they are benefitting from Covid-19 lockdowns even if we aren’t. But does keeping Homo sapiens largely at home actually help wildlife?

The answer very much depends on the extent to which a given species has come to depend on humans, but it’s clear that not all the changes are positive. Even many of those that benefit from more space to wander (and less traffic to play Frogger with) suffer in other ways from lockdown-related changes in human behavior. For every metropolitan mountain lion enjoying a new zip code, there are other animals nearby fruitlessly searching for food.

The small number of species that are particularly well-adapted to human activity have suffered the most from Covid-19 lockdowns. A lack of visitors offering food to local monkeys at temples led to a primate fracas in the streets of Lopburi, Thailand, over a pot of yogurt. (A Thai reporter attempted to interview several local monkeys to hear their side of the story, but they appeared reluctant to speak with him.)

Rats have also seen better days. In New York City, where many normally eat the garbage created by restaurants, some have become more aggressive and cannibalistic from the sudden lack of food, giving an entirely different meaning to the phrase rat race. And maybe worst of all, the downturn in rat fortunes has only increased their nuisance quotient, as desperate rats have become even more brazen than usual by approaching people dining outside as they attempt to finish their meals. In Philadelphia, rats that normally subsisted on restaurant refuse downtown have now moved out to residential neighborhoods in search of greener pastures and fuller dumpsters.

For other species, though, streets empty of people (and their garbage and temple offerings) can be beneficial, especially ones that lack adaptations to deal with oncoming traffic. Opossums play dead and hedgehogs curl up into a ball to deter approaching predators, but these behaviors are counterproductive when the approaching predator has four wheels and weighs two tons.

Fewer cars on the road lowers the chances of these unlucky encounters between cars and wildlife. A Pennsylvania wildlife center normally inundated with calls about injured opossums in the spring didn’t receive any this time. It's estimated that hundreds of thousands of hedgehogs die on British roads annually, but early evidence suggests that many more of them will survive this year.

Animals of all sizes benefit from this. A report on roadkill in California, Idaho and Maine found that there could be between 5,700 to 13,000 fewer deaths of large mammals like deer, moose, and bears in those three states alone due to less vehicular travel. (More bears do mean that park visitors may have to keep a closer eye on their pic-a-nic baskets, though.) At the other end of the spectrum, untold numbers of pollinating insects, of which hundreds of billions are hit by cars each year, will live to pollinate another day.

With fewer cars on the road and closed factories, pollution and emissions have also temporarily declined, which is obviously a good thing for most species. This is not a permanent change, though, and government attempts to kickstart economic growth through relaxing regulations could end up significantly increasing pollution in the long run.

And even benefits such as these can be offset by environmental setbacks elsewhere, unconnected though they may be. Plastic bag use, for instance, has increased as an alternative to reusable bags due to fears that the latter could help spread Covid-19. That will likely lead to more plastic bags in the ocean, which are often fatal to wildlife who mistakenly try to eat them.

Ironically, the lack of industry and activity can also have a lot of negative spillover for animals. A combination of unemployment and the absence of visitors and staff in wildlife preserves due to park closures has created a huge opportunity for poachers around the world to hunt endangered species sought for their skins, teeth and horns.

Poachers have targeted everything from tigers, rhinos and leopards to the pangolin — the world's most illegally trafficked animal, worth over $300 a pound. It’s worth noting that this illegal trade may have even gotten us into this mess in the first place, as it’s possible Covid-19 first infected humans through contact with pangolins infected with the virus. And even far less valuable animals may find themselves hunted simply for meat.

Poachers aren't the only criminals taking advantage of the "closed" signs at park entrances. With the authorities focused on the pandemic, illegal clearing of forests for timber and ranchland has increased in several countries. This leaves less habitat for wildlife and puts more of them at risk of extinction, increases carbon emissions, and may even harm the local economy by reducing future ecotourism revenue.

Even in the United States, where illegal poaching is less rampant, the reduction in state and local revenue from taxes as well as visitor fees creates financial challenges for the many agencies that protect wildlife on state and local government lands. State governments alone own nine percent of the total land area in the United States.

Ultimately, we won't know the full effects of lockdowns until well after the pandemic has ended and more research has been completed, though we do know that the results will not be universally good or bad for all species. But it’s important to remember that human actions responding to human problems can have effects reaching far beyond those most obviously affected — from mighty rhinos to humble bumblebees.