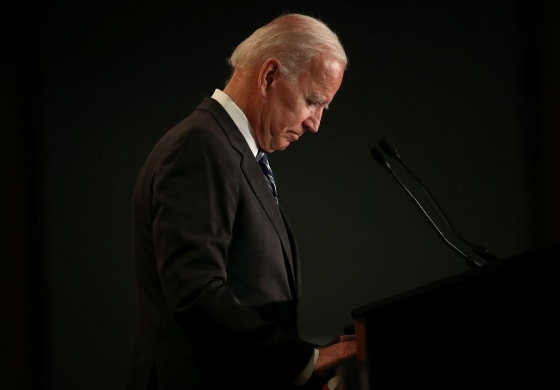

The 2020 presidential election is just beginning, but for some survivors of sexual assault and harassment it feels more like a continuation of 2016 — the election where a guy accused of sexual misconduct by more than 20 women won. Democratic presidential candidate Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand has already had to navigate criticism for helping to hold former Democratic Sen. Al Franken accountable for allegedly groping a woman while she was sleeping, and presidential hopeful Sen. Bernie Sanders apologized for sexual harassment campaign volunteers say they endured during his 2016 bid. But it’s the recent allegations levied against former Vice President Joe Biden that have truly reinvigorated the national conversation about what constitutes sexual misconduct, and what should be considered “disqualifying” conduct for a potential presidential nominee.

As the talk show takes and Twitterati chatter kicks into high gear, the question of motive has taken center stage once more. But for survivors of sexual assault, these public debates can have very personal consequences.

Recent allegations levied against former Vice President Joe Biden have reinvigorated the national conversation about what constitutes sexual misconduct and what should be considered “disqualifying” conduct.

On March 29, former Nevada state assemblywoman Lucy Flores penned an op-ed for The Cut detailing a 2014 encounter with Biden that she said made her uncomfortable. Flores writes that Biden got close to her from behind, “leaned further in and inhaled my hair” and then “proceeded to plant a big slow kiss on the back of my head.” Biden quickly responded to Flores’ allegations, saying that in his “many years on the campaign trail and in pubic life” he has “offered countless handshakes, hugs, expressions of affection, support, and comfort. And not once — never — did I believe I acted inappropriately.”

Then a second woman named Amy Lappos came forward, accusing Biden of “inappropriate behavior” when he “reached for her face and rubbed noses with her” during a 2009 fundraiser in Connecticut. Since then, two more women have come forward with allegations of inappropriate behavior involving Biden, including a sexual assault survivor.

These multiple allegations were followed by a two-minute long video mea culpa from Biden. “Social norms began to change,” he said. “They’ve shifted, and the boundaries of protecting personal space have been reset — and I get it, I get it. I hear what they’re saying. I understand it. And I’ll be much more mindful."

Other women have also come to Biden’s defense, including Stephanie Carter, the wife of former Secretary of State Ash Carter, who said a now-viral picture of Biden grabbing her shoulders and kissing the back of her head during her husband’s swearing in was really just a snapshot of Biden "helping someone get through a big day, for which I will always be grateful."

Neither Flores nor Lappos describe their encounters with Biden as assault, but say his behavior was inappropriate and made them feel uncomfortable; a moment where someone with an immense amount of power felt entitled to another woman’s personal space and acted on that entitlement. And as Flores noted in a statement: “I’m glad Vice President Joe Biden acknowledges that he made women feel uncomfortable… and yet he hasn’t apologized to the women he made uncomfortable.”

Both women have also said Biden’s history of inappropriate behavior with women should disqualify him from entering the 2020 presidential race. House Majority Leader Nancy Pelosi, for one, disagrees — at least on the disqualifying part.

Biden may still end up running for president. But the backlash Flores and Lapps have endured as a result of their willingness to share their stories publicly has been intense — people have accused Flores of being a Bernie Sanders “operative” and have shared pictures of her hugging and/or touching other politicians as celebrates as so-called “proof” she has ulterior motives to coming forward. “Sadly, every last thing I feared would happen, did happen,” Flores said on Twitter. “And I feared it because it’s what every single woman who speaks out against powerful men have faced in the past.”

It’s a sadly predictable reaction. It was only a few years ago, after all, that then-presidential candidate Donald Trump bragged about grabbing women by their genitals without their permission. The revelation sparked hours of television debates and barrels of spilt ink as pundits argued over what constitutes assault and what’s just “locker room talk”; what makes an allegation “credible” and why a woman would come forward. And then Trump won anyway.

Today, neither the cable news pundits nor the internet broadly seem to be able to agree on the definition of sexual abuse, harassment and inappropriate touching. And it seems we’ve learned little from 2016. Regardless of the perceived severity of the incident, women are still too often to blame. Instead of being treated as the foremost authorities on our own experiences, we’re being told we’re wrong, we’re too sensitive, or we’re at fault.

“Anytime we put labels to what we objectively think is better or worse, we’re just being naive and missing a huge part of the picture,” says Jessica Tappana, a licensed clinical social worker and owner of Aspire Counseling in Columbia, Missouri. Tappana says the way we characterize a traumatic event — whether it be rape, sexual assault, or harassment — doesn’t determine how the people who were violated feel. And because many survivors of sexual assault already try to convince themselves that their experiences “weren’t that bad,” Tappana says, hearing family members, friends and elected officials try to rank an individual’s trauma or experience can make that internal seed of doubt grow.

Instead of being treated as the foremost authorities on our own experiences, we’re being told we’re wrong, we’re too sensitive, or we’re at fault.

“So often I see the people who caused harm respond in the worst ways,” Alison Turkos, 31, tells me. Turkos remembers how devastated she felt watching Trump supporters in 2016 condone and excuse his behavior towards women. “At that point in my life I had been raped twice, and I told no one,” she said. Sadly, she fears very little has changed in two years. Sadly, she’s now seeing much of the same.

Indeed, the lasting impact of the 2016 election cannot be understated. Greg Kushnick, a psychologist practicing in Manhattan, says he has seen a number of New Yorkers with PTSD who reported feeling violated after the 2016 election. “They described a sense of impending doom, both personally and culturally,” he tells me. “They described a sense of lacking personal safety, which bordered on annihilation anxiety for some people. They experienced symptoms of depression and felt stuck on issues of morality and fairness.”

Public stories of sexual assault impact survivors of sexual assault differently, according to Kushnick. Some survivors may feel anger, others may even re-experience their own trauma. But it’s not just the stories that effect survivors; It’s the way those stories are discussed.

“That’s the part that people forget,” Tappana the social worker says. “If you’re a woman who has not told her parents that she was sexually assaulted and you’re listening to your parents question the credibility of someone on the news…. [you] start having those thoughts of, ‘Well, that might be my dad’s response if I was to tell him what happened to me.’”

Watching friends and loved ones dissect allegations is a nightmare scenario, no matter what the truth turns out to be. Mallory McMaster, the president and CEO of The Fairmount Group, wasn’t looking forward to Sherrod Brown’s potential 2020 bid for that very reason. During the 2018 Ohio Senate election, Brown’s Republican opponent Jim Renacci claimed multiple women contacted him with claims Brown had assaulted them. Brown refuted those claims, and his ex-wife condemned Racci’s attacks as an attempt to score “cheap political points.” But McMaster has little faith in anyone’s ability to engage in nuanced conversations when these types of allegations are mixed with politics, she says, and was relieved when Brown decided not to run. “Now that Joe Biden is gaining steam though, I feel those same worries creeping up again,” she tells me. “Would these same people [doubting Biden’s accusers] be so quick to doubt my story if I told them about my sexual assault? I really don’t know anymore.”

Stephanie Loraine, a social worker and the president of the Central Women’s Emergency Fund, told me that this idea that survivors come forward for attention is particularly frustrating. A common talking point is that people report their assaults because they have “something to gain,” she says. “There is a spectrum of experiences that should be honored.”

Kushnick advises survivors to create a plan for election coverage and monitor their intake of the news. “Maintain a self-preservation mentality by avoiding what hurts you,” he advised. “Take breaks from media coverage. Consider meeting with a mental health professional to monitor your PTSD symptoms.” Kushnick says it might also be helpful to meet in person with like-minded people or other survivors of trauma. The point is not to ignore the news or repress your reactions to it. Instead, seek out healthy ways to safely process your emotions.

Americans need to be able to have complex conversations about the ways in which powerful men wield their influence. And this country needs to stop relying on one-dimensional narratives of bodily autonomy when it evaluates which stories of sexual misconduct we believe. Will 2020 be the year we finally get it right? So far, many survivors aren’t betting on it.