The real Cinderella story featured an outcast, unnamed daughter of a marriage torn asunder, bequeathed to a stepmother and two insufferably spoiled old sisters, who drew her name from the black soot that soiled her skin doing household chores. In a stunning turn of events, she was able to crash a private party designed to find the prince a wife, wearing a borrowed gown and scrubbed free of the substance that darkened her skin, and charmed him to the dismay of others.

It's a tale we've told children for nearly half a millennia, that love prevails over class, social status — and, perhaps in the 21st century, ethnicity. But, at it's core, it's also about a woman stained dark so as to render her obviously undesirable until, scrubbed into whiteness, she is able to attract the favor of a prince.

So maybe it's not fair to call Meghan Markle's engagement to Prince Harry a "Cinderella" story, even if you're referring to the far-superior 1997 movie version starring Brandy and Whitney Houston, leading an all-black cast, and even if she is descended from one-time British royalty on her father's side… and an enslaved American on her mother's.

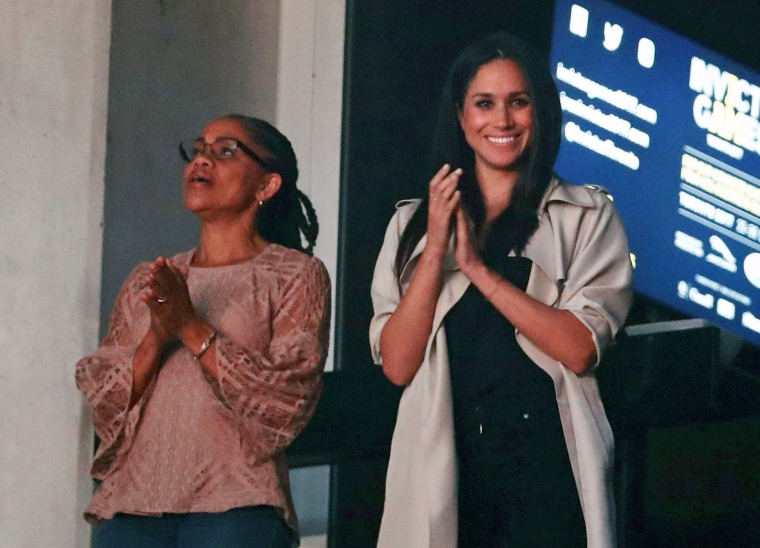

Markle is a biracial woman who affirms her black American heritage, the child of an African American mother and a Caucasian father who split when Markle was two but raised their child into a grounded woman who was aware of the dichotomies imposed upon her because Americans’ thick lines of racial caste, and wholly aware of the inequities in society growing up on Los Angeles. She had a pretty American upper middle class existence, including a private elementary and secondary school education and an undergraduate degree from an elite American university. After that, she pursued an acting career while working a series of odd jobs until she landed the role of Rachel Zane in "Suits," in part, she 's written, because the producers weren't seeking to cast the part for a particular kind of "look."

No one, not even Markle, could have ever imagined that someone like her would ever be permitted to marry a prince. And yet, the British aristocrat will marry an American paradox, and it all feels very right and true — except to those people to whom it is unfathomable not so much that a prince might marry a "commoner" or an American or a divorcée (as that's already happened), but that he might marry one who isn't white.

This toxicity was never more visible than late last year, when the British tabloids ran smears of Markle, mining through her personal life to spin a salacious yarn — dripping with racism — of Markle’s background. They constructed and perpetuated a narrative of black American identity, one in which a black woman couldn't be raised in a world with both access to money and agency. In attempting to paint Markle as a product of a “broken home” who grew up in supposedly blighted Los Angeles neighborhood of “Crenshaw” (her mother’s home is Inglewood Heights, one of the wealthiest black neighborhoods in LA also known as “Black Beverly Hills”) and supposedly appeared in films unbecoming to a potential future royal (though the scenes in question were ripped from her television series and simply posted, in a likely violation of copyright, on a pornographic aggregation site). The dominant narrative of American blackness, even in another country, remains inextricably intertwined with classism, racism and misogynoir.

But not long after that willful race-baiting swill was published, the Kensington Palace communications secretary released a statement at the behest of Prince Harry, demanding that the wolves fall back from their frenzied coverage of Markle. It was at that moment that many understood the seriousness of the prince's intentions towards the woman he was seeing: “Prince Harry is worried about Ms. Markle’s safety and is deeply disappointed that he has not been able to protect her,” the statement read. It was an unprecedented statement from the throne of what was once the world's foremost colonial power, firm and direct in addressing dog whistles and signalling of stereotypes. After all, what is a prince who cannot protect his soon-to-be-betrothed? And women of color noticed that one of the most eligible bachelors in the world came to the defense of a non-white woman.

Since Harry is but fifth in succession to the throne, the rigid rules of royal marriages could, more so than for his older brother, be augmented — perhaps especially because, if Queen Elizabeth has learned anything about the sustainability of the crown, the long-term happiness of her progeny is paramount. Besides which, in modern-day Britain and America, calcified notions of courtship, desirability, identity and class are finally shifting outside the palace walls and now within: A 2014 Office of National Statistics report noted that one in ten Britons are married or living with someone outside their ethnic group.

The British monarchy, however, remains a symbol of imperial power, and is historically responsible for the formation of institutions that segregated indigenous peoples, plundering their lands, murdering their families, fomenting future wars after the resources were drawn out of the territories, imposing borders where none existed before, reshaping world politics and denying millions of people of color any agency or access to this amassed largesse. Yet, for many of us who live in or come from countries once part of the vast empire of British colonial rule, the fascination with the crown is complicated, filled with equal parts disdain and devotion.

The monarchy holds a mystique for common people grasping at some signal that there’s humanity in such resplendence to which we ourselves aspire. And yet, we cannot deny or ignore its active role in the conquest of global peoples, and the legacies of the social and political order it created. We still live with the stain of its arcane rules that govern our perception and relationships with each other.

For instance, colonialism and imperialism placed a higher care and value on white femininity and desirability, and the systems that were created by imperialism upheld her rank over all women, protecting her while imprisoning her, giving white women a false sense of security of their place. And in that ranking of beauty and merit, that fantasy of worth has created a world of hurt and humiliation for women of color.

This is why Markle’s engagement to Prince Harry is remarkable: The old colonial order has eroded, at least in part, among even the remaining aristocracy, with at least some of them recognizing the beauty and value of non-white women in Western societies. Black women are the least desirable in the western imagination — a myth that has masqueraded as truth for some time — and Markel, unwittingly, is by proxy the proof that brown and black women are worthy too.

Maybe it's just another fairy tale, sure — one of a woman whose darkness does not scrub off and yet is still the beloved of the most eligible prince in the land. But when you're raised on tales of pale-skinned blonde women who need but a shower and a dress to win a heart of the prince, a new kind of fairy tale is one worth telling for all the little girls who need to feel worthy of love in the skins we are in.

Syreeta McFadden is a writer and professor of English at the Borough of Manhattan Community College, City University of New York. Her work has appeared in the New York Times Magazine, Rolling Stone, BuzzFeed News, and elsewhere.