History teaches that doing the bidding of a president does not shield subordinates from the consequences of breaking the law. Whether in Watergate in the 1970s or the Iran-Contra affair in the 1980s, a president’s immunity from prosecution for acts while in office has not spared senior administration officials from being indicted for acting illegally in carrying out presidential directives.

That specter complicates the decision faced by current administration officials whose testimony has been sought by Congress in its impeachment inquiry. President Donald Trump’s order that they refuse to testify has had the side benefit of allowing them to hide their own actions from Congress and the public. On the other hand, it exposes them to the Republicans' talking point that the officials were rogue agents in dealings with Ukraine.

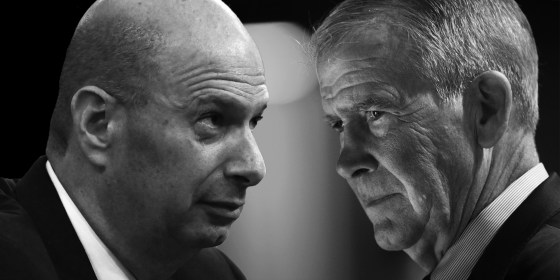

The U.S. ambassador to the E.U., Gordon Sondland, decided to testify. On his third attempt to explain his role in Ukraine to the House Intelligence Committee, he sought to protect himself by swearing that he was acting “at the express direction of the president.” But if Sondland made this assertion in the belief that invoking the president’s role would protect him from potential criminal liability, he is woefully mistaken.

The president's scheme, Democrats argue, was intended to trade military aid to Ukraine or an invitation to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy for a White House meeting with Trump, for Ukraine’s announcement of an investigation into Joe Biden and his son Hunter — which could be seen by prosecutors as bribery, extortion or illegal campaign finance violations. If so, Sondland could be prosecuted even if, under existing Department of Justice policies, Trump cannot.

And Sondland is not the only one to face potential legal exposure. According to Sondland, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, Office of Management and Budget head Mick Mulvaney and Rudy Guiliani were all “in the loop” on Trump’s plan to have Ukraine investigate a Trump political opponent.

The law, however, has a more formal term for being in a “loop” to obtain an illegal act: conspiracy. And even though Ukraine never announced the investigation, a conspiracy to commit attempted bribery or attempted extortion runs afoul of federal criminal statutes even if the effort ultimately failed.

Prosecuting Trump aides for illegal acts the president requested they perform would not be without precedent. Multiple White House and administration officials serving both Presidents Nixon and Reagan were indicted and convicted for federal crimes committed by them in furtherance of presidential objectives.

In the Watergate cover-up, three key Nixon aides — Chief of Staff H.R. Haldeman, White House adviser John Ehrlichman and former Attorney General John Mitchell — were indicted and convicted for conspiracy to obstruct justice, including hush money payments to Watergate defendants, obstruction of justice and lying under oath.

In its final report, the House Judiciary Committee found that Nixon had directed those subordinates in the cover-up including his “directive to Haldeman on June 23, 1972, to have the CIA request the FBI to curtail its Watergate investigation.” That directive ultimately led to Nixon’s downfall: Following the Supreme Court decision ordering the release of White House tapes, the recording of the June 23 meeting was called a “smoking gun” that led Republican congressional leaders to persuade Nixon to resign.

At Haldeman's sentencing hearing, his lawyer, John J. Wilson, told Judge John J. Sirica that “whatever Bob Haldeman did, so did Richard Nixon.” He added, “I hope that your honor considers whatever Bob Haldeman did, he did not for himself but for the president of the United States.” The court, though, was unmoved: Haldeman was sentenced to 30 months to 8 years in prison; so were Ehrlichman and Mitchell. Haldeman served 18 months before he was paroled.

In the next decade, another set of senior government officials learned the same hard lesson. Acting at the behest of then-President Ronald Reagan, officials became involved in the sale of arms to Iran despite an embargo and used of some of the proceeds — in direct contravention of a congressional ban — to aid guerrillas fighting in Nicaragua. The episode, called the Iran-Contra affair, was investigated by an independent counsel, Lawrence Walsh.

After carrying out Reagan’s orders, and thereby committing acts for which they eventually faced legal liability, 14 officials ended up being indicted in connection with the scandal on charges including perjury, withholding evidence, obstruction of justice, false statements and more. The defendants included national security advisers John Poindexter and Robert McFarlane, Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger, Assistant Secretary of State Elliott Abrams and White House aide Oliver North.

An internal analysis by a lawyer on Walsh’s staff, which was publicly released in 2011, recounted what Weinberger said to Reagan — who approved the operation — in a White House meeting on Dec. 5, 1985. Weinberger raised the prospect that they might all end up in jail, adding “visiting hours are on Thursdays,” according to the report.

Of the 14, nine defendants were convicted, one case was dismissed and, while North and Poindexter were also convicted, their convictions were reversed on appeal. The final two defendants (Weinberger and a CIA supervisor) were awaiting trial in December 1992 when President George H.W. Bush, having just lost his re-election bid, pardoned the two and four others who had been convicted. In granting these pardons, Bush was acting on the recommendation of his attorney general, William Barr, who is now serving in that role for Trump.

Sondland and others may harbor the hope that the president, perhaps at the urging of Barr, will exercise his pardon power for anyone criminally charged in the Ukraine episode. But before putting their faith in such a prospect, they may want to see how that worked out for former Trump helpers Michael Cohen, Paul Manafort and Michael Flynn — all of whom were prosecuted and convicted, and two of whom are already serving time.