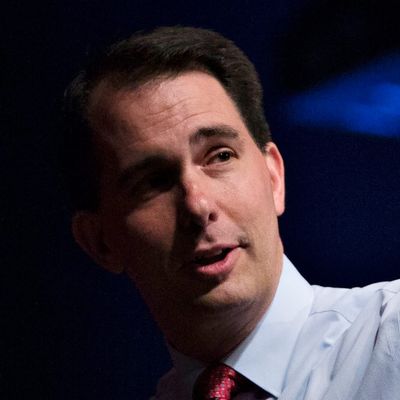

Scott Walker won three statewide elections in Wisconsin, which has supported the Democrat in every presidential election since 1984. He led national Republican polling as recently as March. He led in Iowa by enormous margins as recently as August. The Koch brothers loved him. Walker had spent his entire adult life developing an almost superhuman fealty to the principles of the modern Republican Party, its Reaganolotry, and, above all, a ruthless commitment to crushing its enemies beneath his boot heel. If there was anything that gave Walker joy, other than eating copious amounts of trayf, it was the goal of wiping organized labor off the map. As Grover Norquist enthused in May, “when you meet him, it’s like seeing somebody who sits on a throne on the skulls of his enemies.” The collapse of his presidential campaign, culminating with his departure today, has taken place with head-spinning speed.

Walker was not exactly terrible at running for president, but he was not especially good at it. He entered the race with an ideological advantage: Never having served in Washington, he could position himself in his party’s center, allowing him to woo Republican elites without alienating its activists. But Walker bungled this advantage into a handicap, alienating both camps without fully winning over either one. He waffled back and forth on immigration, leaving nativists suspicious he would remain on their side in office and business elites uncertain how he could reverse the party’s slide with Latino and Asian-American voters. Wealthy New York donors came away from discussions with Walker concerned that he actually believed what he said in public about same-sex marriage. (The Washington Post reported in June, “he has struggled to make inroads among the powerful and monied financial community — in part because of his strident opposition to same-sex marriage and his positions on other social issues.”) Walker’s money problems proved fatal, leaving him unable to finance a going operation.

He proved embarrassingly uninformed about foreign policy, using his victory over unions as an all-purpose response. “Look, he’s the governor of Wisconsin,” Morton Klein, the president of the Adelson-backed Zionist Organization of America, told Jason Zengerle, “He knows about cheese and cutting pensions.” He repeatedly regaled audiences with a story about buying a shockingly inexpensive sweater at Kohl’s, which seemed less like a rationale for electing Walker than a rationale for electing Herb Kohl. In two national debates, he withered onstage next to the highly telegenic performers.

Walker’s poor debate showings may have done him more damage than it even appeared at the time. When your essential selling point is that you are a winner, you are unusually vulnerable if you start to look like a loser. It grew increasingly difficult to envision Walker sitting on a throne of skulls when he sat meekly at the foot of Donald Trump. And Trump’s rise surely destroyed Walker more than anybody else. Trump coalesced the Republican working-class base, which was supposed to be Walker’s base, and the nativists who found Jeb Bush and Marco Rubio too squishy. He grabbed a polling lead in the state (Iowa) that sat at the heart of Walker’s geographic strategy. No other candidate had staked out an early state that they insisted they must win.

The Republican presidential race has appeared to take the form of a kind of reverse meritocracy, in which the candidates with real political accomplishments (Walker and, before him, former Texas governor Rick Perry) are driven out, and novices with strong television skills rise to the top. The reality, however, does not quite match the appearance. The GOP has faced a coordination problem — it has too many acceptable, Establishment-friendly candidates in the race. Any number of viable options presented themselves as vehicles for the agenda of the Republican donor class: Marco Rubio, Jeb Bush, Walker, not to mention riskier choices like Carly Fiorina, Perry, Bobby Jindal, Chris Christie, or even Rand Paul. If the Republican elite coalesced around any of these candidates, they could defeat Trump, or Ben Carson. The party needed some of these candidates to fall by the wayside more quickly. But even a few weeks ago, nobody would have guessed that Walker would have been one of the first to go.