Friday afternoon in Chicago, a 32-year-old black woman named Nykea Aldridge was shot and killed in the city’s South Side while pushing her baby in a stroller on the way to register her children at a nearby elementary school. The mother of four was struck in the head as two gunmen attempted to shoot a man she was walking next to, but the baby was not injured. As the Chicago Tribune reports, Aldridge was one of four people shot and killed in the city on Friday, and another 18 were wounded in shootings that day as well. All told, more than 2,600 people have been shot this year in Chicago, mostly in black neighborhoods on the city’s South and West sides, and the city is on pace to record the largest number of murders since 1997.

But Ms. Alridge was not just another victim in Chicago’s crime epidemic, she was also the first cousin of basketball star Dwyane Wade, who is from Chicago and recently returned to the city after signing a contract with the Bulls. Wade has spoken out about his cousin’s death, which he has also immediately connected to the larger problem of rising gun violence, an issue he has already been working on off the court:

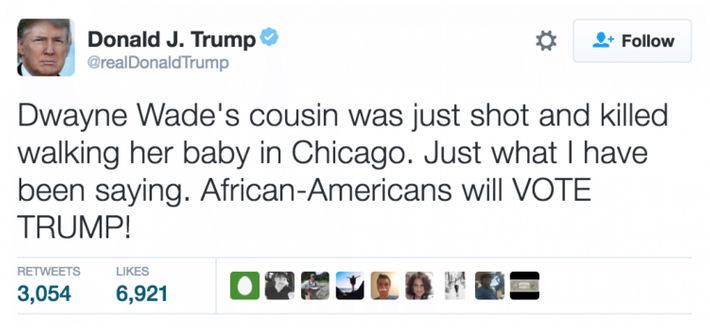

Donald Trump, however, saw the story on Saturday morning and characteristically decided that the person he most wanted to help was himself, which he tried to do by connecting Aldridge’s death to the latest redirection of his presidential campaign:

Trump is of course referencing his new “appeal” to black voters, a demographic whose support for Trump hovers in the low-single digits in most polls, and who, in the Trump campaign’s own focus groups, have accurately described the candidate as “racist” and “unqualified.”

Trump’s new strategy, so far as we’ve seen it in action, is to convince black Americans that, despite all evidence to the contrary, he is the one who cares about them and will bring law, order, and economic relief to their neighborhoods. He is absurdly trying to argue that he is to the left of Hillary Clinton on criminal-justice reform, and trying to make black Americans “realize” how terrible their lives are in an effort to blame Democrats for not having done enough to deserve the community’s support. As an example of the new pitch, here’s what Trump told an audience in Texas this week (and keep in mind that he typically makes these appeals to white audiences):

With rates of crime, with rates of poverty like you’ve just heard, what do you have to lose? I will fix the problem … I say this to the African-American community, “Give Donald Trump a chance.” We will turn it around. We will make your streets safe so when you walk down the street, you don’t get shot, which is what’s happening now.

This is obviously the argument he’s alluding to in his tweet about the death of Wade’s cousin, but it shouldn’t be taken in good faith. As Dara Lind explained this week at Vox, Trump’s new appeal to black voters isn’t so much an actual appeal to black voters, but an effort (by the campaign’s new brain trust) to engage the shrinking base of white, anti-Hillary Republicans who are increasingly turned off by Trump’s racism and offensive comments. Lind writes that these voters now need reasons to show up at the polls, and Team Trump is trying to give them one on race:

The traditional Republican narrative on race has been that it should no longer be relevant to American life. People who really care about race are racists, no matter their skin color. David Duke is bad, but Black Lives Matter is also bad (or at least inherently suspect), because “all lives matter” ought to be an uncontroversial statement in 2016. They may not believe the Republican Party needs to be more proactive in reaching out to nonwhite voters, but they certainly believe the party shouldn’t be doing anything to deliberately drive them away.

Donald Trump — and, particularly, some of his more enthusiastic supporters — aren’t exactly plausible messengers of post-racial harmony. Trump’s used the ethnicity of a federal judge as a character flaw. His campaign routinely ejects nonwhite people, including supporters (and local Republican officials), from his rallies. David Duke is running for Senate because Donald Trump has made white supremacy great again. It’s enough to make any Republican who believed that racism was over in America feel vaguely queasy.

Crucially, though, these are voters who believe that racism is a matter of intent — not effect. They don’t necessarily need to see their party get more diverse to believe that it’s doing the right thing. When Trump tells white voters that he is reaching out to black voters, that soothes their biggest concern: He’s not trying to divide the country along politico-racial lines.

But even without applying that logic, it’s hard to believe that Trump’s tweet about a black mother being randomly gunned down in Chicago had anything to do with actually wanting to help the black community, and as anyone who’s been paying attention for the last year will also recognize, it fits a clear pattern of how Trump uses these types of news events. Indeed, there is now ample evidence that Trump’s initial response to tragedies is an attempt to redirect attention to himself. At Business Insider, Allan Smith and Harrison Jacobs have compiled Trump’s tweets following the recent terrorist attacks in Orlando, Brussels, San Bernardino, and Paris. In each case, as with the Chicago shooting, Trump has immediately sought to leverage the tragedies to prove himself right about something, as well as steal some of the news coverage for himself.

This is not to say that the standard response of a politician expressing their thoughts and prayers or vowing support for the victims of tragedies has any real-world value, but it at least gives the sense that someone feels empathy, or knows how to practice some kind of restraint, especially in the aftermath of a breaking-news event when all the facts are rarely clear. It is also becoming normal for politicians and public figures to quickly frame their responses to shootings to reflect their positions on gun control, but Trump isn’t exactly known for his long-term political beliefs or any reliance on long-term political strategies. Instead, the only consistent characteristics across Trump’s responses to these tragedies are his lack of compassion, his need for attention and self-aggrandizement, and his reckless impulsivity. If there is a real strategy involved, as Lind speculates, then it was likely conceived by someone other than Trump.

As an example, Trump surely wrote the original Chicago tweet himself — he misspelled Dwyane Wade’s name and made a bizarre illogical leap to forecasting his own electoral prowess — but that tweet was subsequently deleted and replaced with one where the spelling was correct. Then, two hours after the initial tweet — likely after someone on the Trump campaign realized the misstep, and either got Trump to give a more normal, human response or just tweeted it out themselves — Trump tweeted again:

Politico reports that Trump also referenced Aldridge’s death in more measured, teleprompter-like terms at another essentially all-white rally in Iowa on Saturday:

It breaks all of our hearts to see. It’s horrible, it’s horrible and it’s only getting worse. This shouldn’t happen in our country; this shouldn’t happen in America. We send our thoughts and our prayers to the family, and we also promise to fight for a better tomorrow.

He also cited the “deplorable conditions in many of our inner cities” and insisted that, “As a father, as a builder, as an American, it offends my sense of right and wrong to see anyone living in such conditions. They are living in terrible, terrible conditions. Beyond belief: bad, bad, bad.”

The rhetoric seemed to convince one white audience member, who told Politico, “I like how he’s addressing the issues with the blacks, how they’ve been held down for 50 years by Democrats,” adding that, “I like that he can go to Washington and shake things up. That’s what we need.”

But if we’re going to consider Trump’s reputation as a builder and paternal white protector of America’s inner cities, it’s worth noting that, on Saturday, the New York Times released a report about the long, documented history of racial bias at properties owned by the Trump family’s real-estate business when Trump’s father was in charge. Though there is no evidence that Donald ever worked on the biased policies himself, the younger Trump did defend the company from federal-discrimination charges, refusing to settle and turning the lawsuit “into a protracted battle, complete with angry denials, character assassination, charges that the government was trying to force him to rent to ‘welfare recipients’ and a $100 million countersuit accusing the Justice Department of defamation.”

While they declared victory in the suit, the Trumps only agreed to stipulations desegregating their properties without an admission of guilt. It’s not clear how much difference the lawsuit ultimately made, however, since five years after it was filed, the government claimed “an underlying pattern of discrimination continues to exist in the Trump Management organization.”

Almost four decades later, Trump wants people to believe he’s on the other side of that fight, but the Washington Post’s Philip Bump makes another point about Saturday’s tweet which seriously undermines whatever credibility Trump is trying to build on the subject:

One of the challenges Trump has faced over the course of his campaign is a refusal to embrace the nuances of American politics. Everything is presented hyperbolically and at its extremes. The idea that black communities suffer thanks to the policies of black Democrats is a long-standing one, but implying that this is thanks to dutiful, unthinking votes being cast by voters incapable of making their own decisions is obviously incorrect (not to mention fraught). Trump here blitzes past the normal considerations of propriety and rhetoric to squeeze a chain of thought into 140 characters: Someone is dead, which is tangentially related to part of his scattershot arguments on race and crime, and therefore this bolsters one of the quivering poles supporting his wobbly pitch to black voters. That’s the utility of the life of Nykea Aldridge as far as Donald Trump can see it.

What’s interesting is that the broader context undermines Trump’s argument. Wade was already active in trying to fight the scourge of gun violence, part of any number of efforts to do so by members of the black community. Trump hasn’t spent much time with that community, so he (as with many others, no doubt) may be unaware of the programs and efforts that are undertaken every day to keep people from being shot in the streets. For example: Wade’s World Foundation, which focuses on helping children and also works to curtail violence in Chicago neighborhoods.

Trump’s interest in the problem is new, mind you. Before the past few weeks, he had rarely mentioned the problem of urban gun violence; before running for office, he doesn’t seem to have ever engaged in trying to help solve the problem.

Lastly, in contrast, it’s worth looking at what Jolinda Wade, Dwyane’s mother and Ms. Aldridge’s aunt, said on Friday night while representing her family following the tragedy. Ms. Wade was once a drug dealer, then turned her life around and became a pastor at a church in Chicago’s South Side. With her sister weeping into her shoulder, Wade insisted that her family’s efforts to confront violence in their community would continue, and they would try to reach people like the ones who killed Nykea: