This is a tale of New Jersey politics. So it is only fitting that it begins — as it will end — in a courtroom. It is the spring of 1978, and a boy wants to sue the government. Charles A. Poekel Jr., a suburban attorney, is staring across his desk at his client, a Livingston High School junior who’s trying to run for a minor office but has been disqualified because he can’t vote. The 16-year-old sits next to his parents, but he does most of the talking. He knows the names of all the county bosses and town committeemen. Poekel understands impatient ambition — he ran for Congress himself at the age of 28. But he’s never met anyone like this boy, David Wildstein.

“It is very unusual that someone of that age would be that all-consumed with politics,” Poekel recalls many years later. “It was like having a child prodigy as a musician, but he was a child prodigy as a politician. I would call him a political Mozart.”

Wildstein takes his case to court. He makes the local TV news, the Times, and the front page of the Livingston weekly paper, the West Essex Tribune, which has been covering his activities since middle school. (It straightforwardly reported his defection from the Democrats to the Republicans at the age of 12.) When the judge rejects his request, the boy remains defiant. “I am in no way over the hill,” he declares, “and can assure the voters of Livingston that they have only just begun to see the name of David Wildstein.”

Video: A Brief History of “Bridgegate”

Back at Livingston High, Wildstein is considered an oddball. He is chubby, with glasses, and a strident conservative. Wildstein doesn’t fit into any of the school’s cliques, but he hangs around the margins of the baseball team. He is a baseball nerd — loves the strategy, the way the game can be broken down into numbers — and acts as team statistician. Livingston is a championship contender, and the players are popular. Everyone loves the catcher, who is the president of the class a year behind Wildstein’s, a beefy jock with a shaggy haircut named Chris Christie.

That May, as Wildstein is trying to run for office, Christie makes the paper for socking a home run into a neighboring swimming pool. Christie’s middle-class family lives in a modest brick home on the other side of town from the Wildsteins, who own a successful manufacturing business and live across the street from the estate of Tom Kean, soon to be New Jersey’s governor. But Wildstein and Christie do cross paths, working together as volunteers on one of Kean’s campaigns and taking a road trip to a rally in Trenton. They are friendly, but then Christie is that way with everyone. He wears his ambition as amiably as a varsity jacket.

Wildstein’s ambition fits him awkwardly, like a grown-up suit a few sizes too large. When he’s a senior, he runs a write-in campaign for the school board on a platform of cracking down on drug use and vandalism. He submits endorsement letters to the local paper from fellow students and his social-studies teacher. The teacher promptly accuses Wildstein of “political manipulation,” claiming he was tricked into signing a letter he hadn’t written. Though they later issue a joint statement, saying the matter was “basically a misunderstanding,” Wildstein still finishes with just 37 votes.

So now it’s 1984. Ronald Reagan is running for reelection, “Born in the USA” is piping out of every radio, and Christie is graduating from the University of Delaware, where he ran the student government and met his future wife, Mary Pat Foster. Wildstein has returned home from Washington, D.C., where he attended college and worked as a congressional aide. He has been managing campaigns for Jersey politicians, including a state senator named Louis Bassano. In an era before ubiquitous computers, Wildstein pores over reams of precinct-level voting results, looking for angles. (“He would spend hours and hours and hours,” Bassano recalls. “I would walk into the office and there he is, looking over the figures, making notes, making notes.”) Wildstein has an obsession with New Jersey political lore, loves the old stories of clubhouse skulduggery.

When Wildstein says he plans to run for office himself, Bassano thinks it’s a bad idea — the kid has got tactical talent but a backroom personality. Wildstein proves him wrong, winning a seat on Livingston’s town council. Two years later, amid a racially tinged uproar over affordable housing, the Republicans win a majority on the council and elect Wildstein to the rotating position of mayor. He is just 25.

“He was quite a phenom,” says Chuck Hardwick, the Speaker of the New Jersey state assembly at the time, for whom Wildstein worked as an adviser. “The talk then was that he was going to be the first Jewish president of the United States.”

But Wildstein is preoccupied with being king of Livingston. “We used to call him the Wild Man,” says his former high-school classmate Leonard Sorge. “He had some wild ideas.” The post of mayor is a part-time position with little power, but he is always at town hall, meddling with the bureaucrats. He shows up early to monitor what time they come to work. Teachers at the high school think he visits an inordinate amount, chumming around with the kids in Key Club, for which he is an adviser.

“He was into everything, he wanted to know everything, and he had something to say about everything,” says Pat Sebold, a longtime Democratic officeholder from Livingston. “He was a major disaster.”

Visiting the high school, Wildstein allegedly tells a group of students that a certain township policeman is “a bad apple.” The cop sues him for defamation. The mayor verbally attacks a municipal judge, claiming that he “continues to take the side of criminals” because he released a pair of shoplifting suspects from Brooklyn. The judge’s admirers are outraged. “I look forward to the time when Livingston will again have a mayor who puts the township first and his own political ambitions second,” Todd Christie — Chris’s younger brother — writes to the Tribune.

Toward the end of his term, Wildstein organizes a coup against the Republican councilman who is supposed to rotate into the mayor’s office next. The councilman accuses him of “terror politics” and trickery. “David’s ploy must be criticized on two counts,” he tells the public. “Most importantly, it was wrong. Secondly, the scheme was doomed to backfire from the start.” That September, facing dim prospects, Wildstein announces that he is dropping his bid for reelection. Democrats retake the Livingston council, which remains in their control to this day.

“A lot of people say that it stays Democrat because of David,” Bassano says. “He would probably have done the party a lot more justice if he had stuck to electing other people.”

Meanwhile, elsewhere in New Jersey, Chris Christie goes through a debacle of his own: a term on the Morris County Board of Chosen Freeholders full of mudslinging, infighting, and litigation, culminating in an ignominious last-place finish in his reelection bid. By the end of the 1990s, both Christie and Wildstein appear to be finished in electoral politics. Christie, an attorney, is back in private practice, working as a lobbyist. Wildstein is running his family’s company, Apache Mills, a leading manufacturer of doormats.

On February 1, 2000, a crudely designed website appears on the internet, run by a person who goes by the name Wally Edge. The real Edge was a newspaper publisher, two-time Jersey governor, and tool of the Atlantic City machine of Enoch “Nucky” Johnson, the inspiration of the Prohibition-era series Boardwalk Empire. The pseudonymous Edge is a purveyor of political gossip. It is actually Wildstein, hiding behind a characteristically obscure historical reference. The same personal attributes that were liabilities to him as a politician — his obsessiveness, his lack of tact, his fascination with personal conflict — prove to be well suited to the internet. The word blogging doesn’t yet exist, but that is what he aims to do, offering readers a mix of score-settling rumors, lobbyist chatter, trial balloons, and arcane trivia.

For the next decade, the true identity of Wally Edge is the subject of much speculation in political circles, but few guess it’s David Wildstein. He’s gotten married and moved to the town of Montville, where he lives in a brick McMansion on two wooded acres. He has been selling floor coverings and doing a little political consulting on the side. One of the politicians he has stayed in contact with is Bob Franks, who represented Livingston in the state assembly during Wildstein’s mayoral tenure. Franks is a brilliant strategist who mentored many operatives. By 2000, Franks is a congressman running a long-shot campaign for the U.S. Senate. In its early days, Wildstein’s site, PoliticsNJ, seems to exist, at least partly, to promote Franks’s candidacy. His regular column, “The Inside Edge,” defends Franks from his primary rivals’ attacks, suggesting they worked out a corrupt bargain to coordinate against him.

Wildstein’s agenda, though, proves to be larger than advancing any one candidate. In a posted mission statement, he says the site “means to inject our views into the political arena.” His biases, he admits, are personal: “We have favorites just like you, and there are some New Jersey pols we really dislike.” Wally Edge’s favorites include three operatives from the Franks campaign: Mike DuHaime, Bill Stepien, and Bill Baroni. All three will go on to become major players in New Jersey politics and key figures in the Chris Christie administration.

Wally Edge is not overtly partisan, though. As they say in baseball, he is a fan of the game. He disdains those he deems phonies and appreciates operators. (“Among those of us who pay inordinate attention to politics in New Jersey, Wally Edge had an unusual seat at the table,” says Robert Torricelli, the Democratic power broker known as “the Torch,” who was a U.S. senator at the time. “I always liked him because I was always one of his favorites.”) Wildstein would sometimes describe his audience as “people who get the joke.” The joke is that, beneath all the theatrics of ideology, politics is about people competing for status. In that sense — and in many others — our institutions of government are not so different from high school.

Chris Christie has found a new calling, too. He spends the 2000 campaign raising money and working as a lawyer for George W. Bush, drawing Wally Edge’s ire when he appears to be cooperating with one of Franks’s primary opponents. But then Bush appoints Christie to be a U.S. Attorney, and he begins to arrest public officeholders for corruption. In New Jersey, criminal investigations are considered to be politics by other means — that’s another part of the joke — and Wildstein is quick to appreciate how cannily Christie is positioning himself. In 2002, the website names him its “Politician of the Year.” It constantly touts his prospects for higher office, attaching “corruption-busting” before every mention of his name.

And there is so much corruption to bust! Christie obtains an indictment for Essex County executive James Treffinger, one of Franks’s old GOP-primary opponents, and has him handcuffed in front of his family home. PoliticsNJ is credited with the scoop and revels in Treffinger’s downfall. After he pleads guilty, the site publishes a Photoshopped picture of the politician in prison stripes. Christie later arrests developer Charles Kushner, a major Democratic contributor, who ultimately pleads guilty to making illegal campaign contributions and retaliating against a witness, his brother-in-law, by luring him into a videotaped encounter with a prostitute. (PoliticsNJ refers to him as a “budding filmmaker.”) Whenever Wally Edge finds out that Christie is investigating someone — as he frequently does, somehow — he writes that the target is “hearing the cellos,” a reference to the Jaws theme.

In 2004, Governor Jim McGreevey, a Democrat, starts hearing the cellos. An FBI informant has caught him on tape uttering “Machiavelli,” which is allegedly a code word signaling his complicity in an illegal fund-raising scheme. The governor hastily resigns, explaining that he is a “gay American” and has been carrying on an affair with a former aide. (PoliticsNJ has been dropping hints about the aide and his “unique skill set” for years.) Republican leaders then try to draft Christie to run for governor, and Edge has an authoritative description of Christie’s thinking as he considers, and then rejects, the opportunity. Christie will always deny leaking, but he definitely appreciates the site’s influence. Long after Wildstein has stopped blogging, Christie still calls him “Wally.”

Wally Edge has more power than David Wildstein ever did. Communicating almost exclusively by AOL Instant Messenger, Wildstein maintains a web of informants inside both parties. Over the years, PoliticsNJ evolves into a real news organization. The site hires a small staff of professional reporters, none of whom know their boss’s true identity. Wildstein turns out to be a good judge of talent. One of the website’s first hires is Steve Kornacki, who goes on to become a political analyst on MSNBC.

Wildstein has dreams of expanding his model into every state, but the site can never generate much revenue from its few ads. In 2007, he decides to sell the site to someone who can invest. An unlikely buyer materializes: Jared Kushner, Charles’s 26-year-old son. Wally Edge announces the sale with his own invocation of Machiavelli: “Whosoever desires constant success must change his conduct with the times.”

The Kushner family is also from Livingston. Charles’s reputation may be tarnished, but Jared has a plan to expand their influence by buying media properties, first in New York (he already owns the New York Observer) and now back home in New Jersey. Wildstein agrees to sell on two conditions: He wants to remain anonymous, and he wants to keep possession of Wally Edge’s AOL email account, which contains much information that might interest the Kushners. (“The repository of secrets that David collected is like nothing I’d ever seen,” says Jordan Lieberman, who managed the business side of PoliticsNJ for years.) Kushner agrees. He tells his employees at the Observer that they could learn something about digital media from Wally Edge, whom he admiringly calls “a wild man.” Wildstein swoons for Kushner, decides he is another prodigy. He ends up attending Kushner’s wedding to Ivanka Trump.

Kushner puts Wildstein in charge of building a national network, and they hire staff in 17 states. But it turns out statehouse gossip is hard to produce at scale. After the 2008 election and the real-estate crash, Kushner decides to abandon the project and lays off most of the staff. Wildstein goes back to running the New Jersey site. The 2009 governor’s race is coming up, and Kushner has a very personal interest in that, because Christie is on the ballot.

Kushner harbors a deep antipathy toward the prosecutor who locked up his father, and Wildstein knows how his new boss wants the race to be covered. “In 2009,” says a former Observer employee, “the site exists to destroy Chris Christie.” When Christie wins, though, the governor is forgiving: He has a job for Wally Edge. He needs an agent at the Port Authority. When Wildstein defects, sources say, the Kushners are furious. Someone leaks Edge’s true identity to the Newark Star-Ledger.

The near-universal reaction among the insiders he covered is: David who? But Wildstein is known to people who matter, especially Mike DuHaime, now Christie’s chief political strategist. Wildstein’s new post, at the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, comes with a huge salary, by government standards, and the specially created title of director of interstate capital projects. It quickly becomes evident that Wildstein is not there to build bridges.

“Wildstein has been waiting his whole life to get into a massive government bureaucracy,” says a former colleague, “with all kinds of nooks and crannies and levers.”

Why would Christie want to turn David Wildstein into a power broker? The Port Authority may look like a boring bureaucracy, but it’s really a self-propelled patronage machine. Every time you cross the Hudson River, or land at one of the region’s airports, or swipe a MetroCard at the World Trade Center transit hub, a coin rings in the Port Authority’s coffers. It has a 1,700-member police force, an army of engineers and lawyers, and the capacity to spend billions of dollars on construction projects. The governors of New York and New Jersey jointly control the authority, and the two sides clash eternally. The New Jersey faction is convinced that it is being cheated out of its fair share of the budget.

Wildstein’s direct boss at the authority is Baroni, his close friend from the Franks campaign, but Wildstein is seen as Christie’s inside man. (“He came directly — like a missile — out of the governor’s office,” says a former Port Authority executive.) Wildstein meets frequently with Christie’s advisers, DuHaime and the other Franks-campaign veteran Stepien, and more occasionally with the governor himself.

“When David Wildstein walked into a room, it was clear that Chris Christie was represented,” says Torricelli, who dealt with the Port Authority as an attorney for an auto-importing facility that had a lease dispute with the agency. “I thought they had rather direct communication.”

Wildstein can imagine many creative ways to put the machinery of the Port Authority to use. (Stepien will later allegedly tell the governor that Wildstein came up with “50 crazy ideas a week.”) And because the Port Authority is an independent agency, Christie can maintain a deniable distance. When the Port Authority needs to raise tolls, Wildstein and Baroni come up with an elaborate ruse to make it look like Christie is heroically fighting the bureaucracy. When the city of Bayonne is about to go bankrupt, they orchestrate a land deal that bails it out, removing the burden from Christie.

Inside the authority, Wildstein makes it plain that he is watching out for the governor’s interests. The civil servants who work at the authority are accustomed to some political interference, but Wildstein’s conduct shocks them. (“It was extreme,” says a former port official. “Full intimidation: ‘I’m Christie’s guy. I rule.’ ”) Co-workers report that Wildstein is seen poking around the office before dawn. He shows up at meetings he isn’t invited to and begins tapping notes on his tablet. In an email to an aide, Scott Rechler, a powerful board member from New York, references the widespread concern that Wildstein may be eavesdropping on phone conversations.

Wildstein clashes with the authority’s professional department heads and conspires to purge low-level employees, replacing them with his own people, who are assumed to be spies. His powers reach into every area: port operations, the airports, the police. There is a rumor that he uses an emergency-access lane to cut the line every morning at the Lincoln Tunnel. One day, during a routine tour of the George Washington Bridge, he notices a set of orange cones are blocking off three toll lanes, offering direct access to drivers approaching the bridge from neighboring Fort Lee. He is annoyed and wants to know why the town appears to have its own entryway. The bridge’s manager tells him there is a long-standing deal with the mayor. Wildstein apparently files the observation away.

By 2013, everyone in Christie’s orbit is working toward one objective: the White House. He is going to run, for sure, and the only question is whether Republicans are ready for a blunt-spoken, sometimes rude northeastern populist with a flair for social media. Christie first has to get past his reelection campaign in New Jersey, but that’s just a formality. He’s so popular that the Democrats only put up a token opponent. In order to demonstrate his centrist appeal, though, Christie’s strategists want to run up the score by winning endorsements from as many Democratic officeholders as possible.

The endorsement push is coordinated by Stepien, Christie’s campaign manager, and Bridget Kelly, a state official who runs the governor’s Office of Intergovernmental Affairs. (The two are also quietly dating.) The governor’s allies at the Port Authority are key players in their strategy. Drawing on a list of targeted mayors, Baroni raids a JFK hangar filled with debris from the Twin Towers and distributes pieces of steel to towns around New Jersey for use in memorials. He and Wildstein conduct so many VIP tours of ground zero that they demand — and receive — a new entry gate for their convenience.

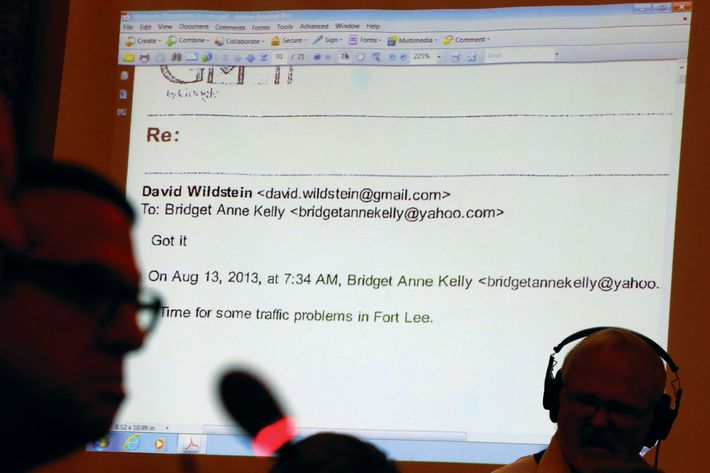

The courtship is not subtle: Mark Sokolich, the Democratic mayor of Fort Lee, later recounts that when Wildstein offered his family a tour, he repeatedly referred to Sokolich as “the one I was told to be nice to.” But after hemming and hawing, the mayor eventually makes it clear to Kelly’s office that he’s not going to back the governor. Soon after, in what prosecutors will describe as an act of political reprisal, Wildstein and Kelly start discussing a scheme. On August 12, 2013, Kelly checks with her staff one final time to make sure they won’t win Sokolich over. Early the next morning, she sends Wildstein a terse email.

“Time for some traffic problems in Fort Lee.”

“Got it,” Wildstein replies.

A month later, on the first day of school in Fort Lee, Wildstein arrives at the bridge at dawn to supervise the implementation of his plan, which he calls a “traffic study.” All the Port Authority employees involved know something strange and colossally stupid is afoot, but no one says anything, because they are all terrified of Wildstein. The cones are reconfigured so that Fort Lee’s access is cut to a single lane. Inside the bridge’s command center, via a live video feed, Wildstein watches as the rush-hour traffic begins to build. Soon, Fort Lee is totally gridlocked: Buses can’t get children to school. “Is it wrong that I’m smiling?” Kelly, a divorced mother of four, later texts Wildstein. “I feel badly about the kids … I guess.” He responds that they are the children of Democrats.

A Port Authority policeman named Chip Michaels texts Wildstein a report from the streets: “Its fkd up here.” Michaels is another guy from Livingston. He and his brother, a Republican lobbyist, have known both Wildstein and Christie for years. Michaels picks up Wildstein and takes him on a drive to observe the traffic. Then they go to a diner, where they have breakfast and discuss Christie’s presidential hopes.

All right, so now it’s September 11, the most solemn day of the whole political calendar, and Chris Christie — the candidate who never neglects to mention he was appointed U.S. Attorney the day before the terrorist attacks — is yukking it up with Wildstein at the World Trade Center site. They’re there for the annual memorial service, but it’s also the third day of the closures, and Wildstein has been monitoring the traffic, along with Mayor Sokolich’s increasingly desperate messages to Baroni. (“Radio silence,” Wildstein orders.) Photos of the event show Wildstein standing next to the governor, checking his phone, and sharing a hearty laugh with Christie, Baroni, and others. No one knows what’s so funny, but Wildstein will later allege that they discussed the bridge. It is the last time he and the governor will see each other in person, at least publicly.

By the next day, Sokolich and others in Fort Lee are screaming about public safety and political payback. The “Road Warrior” columnist for the Bergen Record contacts the Port Authority about the mysterious gridlock, and Wildstein forwards the message to Kelly, who is heading down the shore with the governor, responding to a major fire on the Seaside boardwalk. No one knows what she tells Christie, but the lane closures continue. The Record column draws the attention of the Port Authority’s executive director, Pat Foye, a New York appointee. This is the first he’s heard of a “traffic study,” and he freaks out. He orders the lanes reopened, saying the “hasty and ill-advised” closure is both dangerous and illegal. A couple of weeks later, the email from Foye makes its way to reporter Ted Mann at The Wall Street Journal. Wildstein presumes Foye is waging factional warfare, rather than worrying about ambulances and school buses stuck in traffic.

“Holy shit, who does he think he is, Capt. America?” Stepien texts Wildstein.

“Bad guy,” Wildstein says. “Welcome to our world.”

The Christie administration brushes aside accusations of its involvement in causing the gridlock as an absurd conspiracy theory, but the Journal continues to pursue the story, and other outlets follow. Legislative hearings are called, subpoenas are issued, and the governor and his aides hold crisis-management meetings. As late as December 2, Christie is still trying to laugh off suggestions of retaliation. “I worked the cones, actually,” he says sarcastically at a press conference. “Unbeknownst to everybody, I was actually the guy out there in overalls and a hat.”

One day, Wildstein disappears from his office at the Port Authority headquarters, never to return. He can hear the cellos.

In early December, the dormant Wikipedia account Montclair0055 — whose sparse prior contributions include creating a page for the state senator who gave Wildstein his first paying job at age 12 and laudatory additions to the entries for Baroni and DuHaime — stirs to life. As the clamor of the investigation intensifies, Montclair0055 writes late into the night on subjects that mirror Wildstein’s obsessions, adding a critical entry for an obscure Democratic Party hack who was one of Wally Edge’s favorite targets and another about “the Curse of the 38th,” a phrase (used exclusively on PoliticsNJ) to describe the voting history of a Bergen County legislative district. The editor revises the page of Steve Kornacki to note that he got his start at PoliticsNJ. Montclair0055 seems determined to ensure that the picaresque characters and episodes that so enthralled Wildstein are preserved for posterity. Many of the contributions are later deleted by other Wikipedia editors on the grounds of insignificance.

The night of December 4, Wildstein has dinner in New Brunswick with his friend Mike Drewniak, the governor’s spokesman, and tells him that Christie was aware of the lane closings as they were happening. The message is implicit: He won’t go down alone. The governor’s chief counsel calls Wildstein and tells him his resignation is required immediately.

Wildstein’s subpoena from the state legislative committee arrives on December 12, and he hires a criminal-defense attorney. They could fight to quash it, but instead he hands over 900 pages of emails, texts, and documents. One of those emails is the fateful one from Kelly: “Time for some traffic problems in Fort Lee.” Those eight words are all it takes to ruin several lives.

You can imagine Christie, the former prosecutor, wondering: Why didn’t she just use the goddamn phone? His reputation as an incorruptible truth-teller is rendered ridiculous. Even his hero Bruce Springsteen, in a hilarious knife-twisting gesture, duets with Jimmy Fallon on Late Night in a song about the traffic jam set to the tune of “Born to Run.”*

Christie holds a two-hour press conference, in which he says he was “blindsided” and “humiliated” by the actions of his staff. “Let me just clear something up, okay, about my childhood friend David Wildstein,” he says scornfully. “We didn’t travel in the same circles in high school. You know, I was the class president and athlete. I don’t know what David was doing during that period of time.” Christie’s office later circulates a memo to supporters that describes Wildstein as untrustworthy, citing, among other things, the high-school dispute with his social-studies teacher and his odd habit of registering web addresses for the names of his enemies. In January 2015, Wildstein reaches a deal to plead guilty and testify. Baroni and Kelly are indicted four months later.

Christie decides to run for president anyway. He announces his candidacy at Livingston High School. Inside a sweltering gym bedecked with championship banners, the governor is received by a boisterous contingent of his old friends from the class of 1980. “Lots of people have asked me over the course of last week, why here?” he says. “Why here? Because everything started here for me. The confidence. The education. The friends. The family. And the love that I’ve always felt for and from this community.” Outside the gym, protesters picket the speech, waving signs that read BULLY.

On the campaign trail, he keeps getting incredulous questions about the juvenile traffic-jam prank. He drops out after a poor finish in New Hampshire and endorses Donald Trump. This puts him in the awkward company of the nominee’s son-in-law and strategic adviser, Jared Kushner. Kushner finally bests his father’s accuser, crushing Christie’s hopes of the vice-presidential nomination, but Christie still retains an important place in Trump’s small circle of loyalists. If Trump wins, you can assume there will be a place for him in the administration, perhaps as attorney general.

That prospect must make Wildstein extremely nervous. After the scandal, he moves to Florida, sells the house in Montville, and loses a precipitous amount of weight. When he arrives at court to enter his guilty plea, the reporters covering the case hardly recognize him. By the terms of his deal with prosecutors, he is expected to be the star witness against Kelly and Baroni, who, if convicted, would likely face two to three years in prison. It is rumored that their trial will bring significant further disclosures. Wildstein, the collector of secrets, is said to have walked out of the Port Authority with an enormous amount of documentary evidence, including the hard drive to his former friend Baroni’s computer.

Looming over the trial is the question of Christie’s level of involvement in his old classmate’s crazy bridge idea. Prosecutors have filed a sealed memorandum, listing people who were aware of the scheme; it is widely presumed that Christie’s name is on it. If he is called to testify, the governor will have to tell his story under oath. At a minimum, the spectacle will be embarrassing for Christie and threatening to any future chance of a cabinet post. At worst, the trial could destroy what is left of a career he’d once thought could plausibly culminate in the presidency.

Among veteran observers of New Jersey politics, there is an ongoing debate about who is most to blame for Chris Christie’s downfall. There are essentially two theories. One holds that Christie, a seemingly intelligent adult, would never be so idiotic as to authorize a retaliatory traffic jam. The other holds that Wildstein, a seemingly intelligent adult, would never be so idiotic as to go forward with his scheme without Christie’s approval. The trial is scheduled to begin on September 19. Soon we may hear the rest of the tale and, at long last, get the joke.

*This article appears in the September 19, 2016, issue of New York Magazine.

*This article has been corrected to reflect that Bruce Springsteen and Jimmy Fallon performed a song about the traffic closure on Late Night, not SNL or The Tonight Show.