Harry Reid was searching for someone to take a stand. It was a Tuesday morning in early December, three days before his three-decade congressional career would effectively come to an end, and Reid had summoned about 20 of his staffers to his Capitol office just off the Senate floor. Although it’s reserved for the leader of the Senate’s minority party, it’s still a magisterial space, with soaring ceilings and mosaic floors. As a cold rain pelted the windows, the Nevada senator sat in a high-backed chair in front of a roaring fire. He wore the uniform of a D.C. power broker — navy suit, amethyst cuff links, and shiny brown shoes — but Reid didn’t radiate power so much as desperation.

In a few minutes, he’d be having his final weekly lunch with his Democratic Senate colleagues; immediately after, he would host his final post-lunch press conference. Now Reid wanted his staff to prep him for both as he tried to exercise his last bit of influence on a situation that would soon be totally out of his control: the presidency of Donald Trump.

“What’s your position on the Mattis waiver?” a staffer asked Reid, referring to the waiver that would allow Trump’s secretary of Defense nominee, retired Marine general James Mattis, to serve in the post despite a law barring recently retired military officers from the job.

“The waiver should not be granted in this Congress,” Reid said.

Another aide brought up Joe Biden’s recent remark that he was thinking about running for president in 2020. “Would you support him?” she inquired.

“It depends on who’s running,” Reid replied. “It appears we’re going to have an old-folks’ home. We’ve got [Elizabeth] Warren; she’ll be 71. Biden will be 78. Bernie [Sanders] will be 79.”

For half an hour, Reid and his staffers discussed how, in his final days in the Senate, he could equip his Democratic colleagues with the things they’d need to obstruct Trump’s agenda. But the most pressing issue confronting Reid that morning was far from that day’s headlines. It had to do with how a couple of crucial and much-ballyhooed new federal medical initiatives — one combating opioid abuse and the other promoting cancer research — would be funded next year.

Even here, Reid’s staffers had surfaced yet another worrisome consequence of losing a presidential election to someone no one believed could win. The programs’ funding language was tucked into a spending bill that would keep the government running for the next four months and that would come to a vote later that week; the language appeared sufficiently vague that Reid’s staff was concerned that the Trump administration would have too much leeway in how it spent the money. Rather than send the funds to states with the biggest opioid-addiction problems, Trump might steer it to, say, Texas —“Not that Texas doesn’t deserve opioid money,” Kate Leone, one of Reid’s policy wonks, hastened to add. And the money for the cancer initiative — which, the day before, in an emotional and rare bipartisan moment on the Senate floor, had been named in honor of the late Beau Biden while his father, Joe, presided over the chamber — would be given in a lump sum to the National Institutes of Health, which didn’t necessarily have to spend it on cancer research. “They can use it on regenerative medicine if they want,” Leone explained, referring to another NIH initiative that’s the pet project of Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell. “I don’t think we’d care as much about this if Obama was there for all of 2017,” Leone said.

Reid was perturbed by these assessments, which were news to him. “I have never heard that,” he complained. “In the hour I spent this morning” — with his Senate leadership team headed by Chuck Schumer, Richard Durbin, and Patty Murray — “no one ever raised that.”

The White House was aware of the problem, explained Drew Willison, Reid’s chief of staff, but “the White House as usual wants us to do their work and won’t help us at all with any leverage.”

“I want somebody prepared at the lunch today talking about the opioid funding,” Reid said. “No one has been talking about that.”

Leone suggested Murray for the assignment.

“She sure didn’t say anything this morning,” Reid said.

“She’s hard to motivate,” Bill Dauster, Reid’s deputy chief of staff for policy, conceded. With both parties toasting themselves for passing the feel-good medical initiatives, there were worries that raising nettlesome questions about their funding would seem churlish.

“So am I going to call on her to explain the problem?” Reid asked. He was met with silence. “Bill,” Reid finally said, “if you would put some talking points in my language, I will say it.”

“As my staff will tell you,” Reid said to me when we spoke the next day, “I’ve done a number of things because no one else will do it. I’ve done stuff no one else will do.” I expected him to give an example of a successful parliamentary maneuver or perhaps a brave political endorsement, but instead he mentioned one of the most disreputable episodes of his long career, when, during the 2012 presidential campaign, he falsely accused Mitt Romney of not having paid his taxes. (Even though the facts were wrong, the accusation spurred Romney to release his tax returns, which showed he had only paid 14.1 percent.) “I tried to get everybody to do that. I didn’t want to do that,” Reid said. “I didn’t have anything against him personally. He’s a fellow Mormon, nice guy. I went to everybody. But no one would do it. So I did it.”

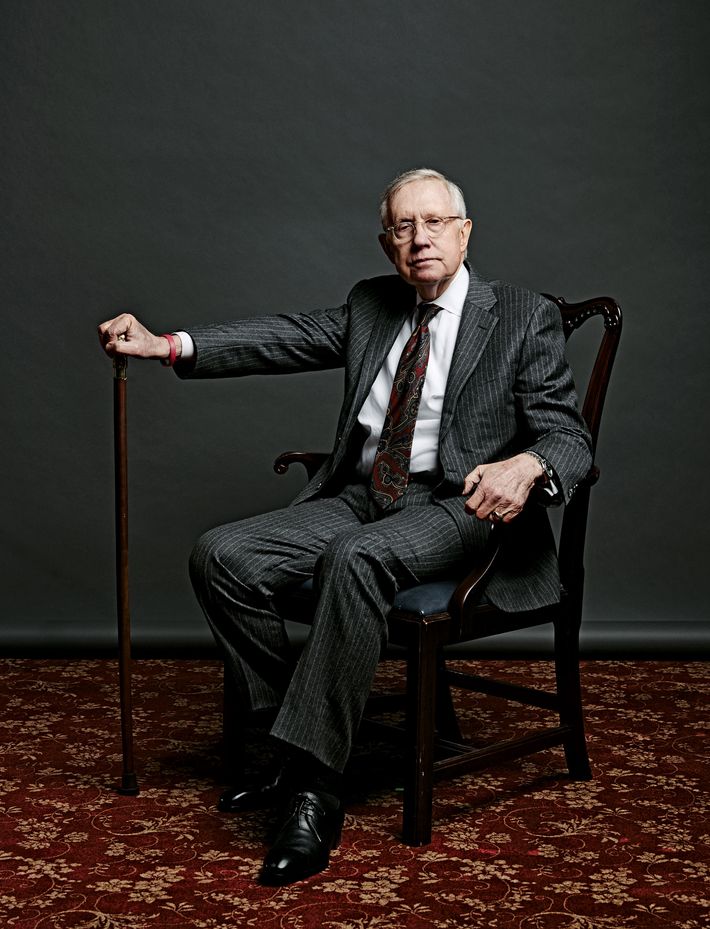

Reid appears significantly older than his 77 years. A horrible exercise accident on New Year’s Day in 2015 — when an elastic band he was using in his suburban Las Vegas home snapped and he tumbled into some cabinets — broke bones in his face, as well as his ribs, and left him blind in one eye. It was his declining physical condition that ultimately led him to decide not to seek reelection in 2016. Today, Reid is extremely hunched and walks with the aid of a cane; his voice, always reedy for a politician, is now sometimes so soft that it’s barely audible. But Reid is as stern and blunt as ever, and the combined effect of his mental and physical condition has given him a Yoda-ish quality. As he busied himself trying to prepare his Democratic colleagues to battle Trump without him, it was easy to imagine Reid as an aging Jedi master training his young apprentices. “It’s hard for someone in my business who tries to ingratiate himself with everybody to do something that you know when you do it, you’re going to have some people not like it,” Reid told me. “We as public servants would be better off not worrying about everybody liking us, because it’s easy to be around here and get reelected and reelected and reelected and not take stands on much of anything.”

For the moment, though, Reid was still there to take those unpopular stands on his own. At the Senate Democrats’ lunch, he raised the issue of opioid and cancer funding. A number of his colleagues, including Murray, then joined Reid in voicing their displeasure with the language to Republicans. And in the following days, as the final language in the legislation keeping the government open was hammered out, the Republicans actually bent to the Democrats’ concerns. It turned out the funding language for the opioid initiative was fine, but the language for the cancer initiative was redrafted, and on Friday night, hours before the government would shut down, the bill garnered just enough Democratic support to pass. It was Reid’s last legislative accomplishment.

As the reality of Trump’s election — coupled with the GOP’s continued control of Congress — slowly sank in among shell-shocked Democrats in the final weeks of 2016, a second, almost equally jarring revelation began to dawn on them as well: They wouldn’t have Harry Reid around anymore to help them deal with this new nightmare.

Although Reid was not the most visible protagonist in national politics — it was Obama, of course, whom Democrats turned to for inspirational words, and unlike, say, Nancy Pelosi or Ted Kennedy, Reid wasn’t a staple of Republican direct mail or attack ads — he was, in Washington, a legendary figure. Especially over the past decade. To Republicans on Capitol Hill, he was an arch-villain — “the worst leader of the Senate ever,” as Mitch McConnell called him in 2013, when Reid, then the majority leader, changed the Senate rules so that only a simple majority, rather than 60 votes, was needed to confirm presidential appointees. “He was bad for the country and bad for Democrats,” says the Republican strategist Doug Heye. But to Democrats, Reid was indispensable — not only the man who helped them win back control of the Senate in 2006 but also the party insider who encouraged Barack Obama to run for president and, later, the parliamentary wizard who helped pass Obama’s legislative agenda. “He was a crucial partner to the president,” says David Axelrod. “I love the guy. He’s canny, relentless, and yet deeply committed to politics as something more than the acquisition of power.”

The man who’ll be replacing Reid as the Democrats’ Senate leader is Chuck Schumer. This is by Reid’s design. The taciturn Mormon from Nevada and the manic Jew from New York were one of the odder couples on Capitol Hill, but they had a remarkably close — and successful — partnership. Democrats talk of the pair’s work during the 2006 midterms — when Reid was the Senate minority leader and Schumer ran the party’s campaign arm — in the tones Yankees fans use to speak of Mantle and Maris. In many ways, Schumer was the perfect complement to Reid. “Senator Reid never cared about messaging, and he sure as hell didn’t care about polls,” says Jim Manley, Reid’s former communications director, “but Schumer certainly thrives on that stuff.” Unlike Reid, Schumer also had good working relationships with many of his Republican colleagues. More than anything, though, Reid — who grew up in abject poverty and moonlighted as a Capitol police officer to put himself through George Washington law school — admired Schumer’s hustle. “He knows that Chuck’s the guy who works his ass off,” says one Reid adviser.

But the job that Reid had in mind for Schumer when he anointed him as his successor isn’t the one Schumer will actually be doing. “Schumer would be a very good majority leader under President Hillary Clinton, and that’s what he thought he was signing up for,” says one prominent Democratic strategist, noting how aggressively Schumer waded into several Democratic Senate primaries in 2016. “He made the calculation that he wanted to win the Senate with people who were easily tamable and then he could be a majority leader like LBJ, just ramming things through.” As a minority leader with a Republican in the White House, however, Schumer will have a very different task — and there’s concern among some Democrats that he might not be cut out for it. “Chuck will go to the ramparts on an issue when it’s polling at 60 percent, but as soon as it gets hairy, he’s gone,” says one senior Democratic Senate aide. “Chuck wants issues to have no negatives, but it’s the Trump era. He’s looking at polls showing 60 percent for the Carrier deal” — in which Trump persuaded the company to keep a furnace plant in the U.S. in exchange for $7 million in tax breaks — “and thinking to himself, Maybe we should support that.”

Indeed, in the days immediately after Trump’s victory, Schumer sought common ground with the president-elect. Other Senate Democrats soon followed suit. Even Elizabeth Warren, who had spent the presidential campaign taunting Trump, pledged to work with him on increasing economic security for the middle class. Much of this was, presumably, typical morning-after posturing, but Reid was nonetheless alarmed. Three days after the election, he released a statement branding Trump “a sexual predator who lost the popular vote and fueled his campaign with bigotry and hate.”

“What I was trying to say,” Reid told me, “is, ‘Be careful, because this is not all fun and games. The stuff he has said has been hateful and disruptive and crude and not helpful to anybody, and so be careful what you agree with him about.’ ” Adam Jentleson, a top Reid adviser, puts it more bluntly: “He was standing athwart the normalization of Trump, yelling ‘Stop!’ He wanted to show Democrats that this is how you should be approaching things.”

The message was delivered, but even though Senate Democrats, including Schumer, have since struck a more defiant tone toward Trump and the GOP, they haven’t been as defiant as Reid might have hoped. Schumer, in particular, has continued to signal a willingness to work with Trump. “We’re not going to say no to something just because Trump’s name is on it,” says Matt House, a Schumer aide. “If people are concerned we’re going to work with Trump, they’re concerned we’re going to work with Trump on things Democrats have been fighting for for a long time. People need to pay attention to the nuances.” But the question remains whether those nuances will be lost on some of Schumer’s Democratic colleagues.

Nearly two months after the election, Senate Democrats are by all accounts unprepared and without a coherent strategy when it comes to opposing Trump’s agenda. Should they obstruct at all costs, even if it grinds government to a halt, and risk criticism that they’re just as partisan and ruthless as Republicans were under Obama? Should they partner with Trump in areas where he disagrees with GOP orthodoxy and hope that voters reward them as the party out of power? Should they prioritize delegitimizing Trump and winning 2020 — or defending vulnerable Senate seats in 2018? It is in the Senate where, theoretically, Democrats have the best shot at countering almost total Republican dominance of Washington. But to be effective they will need to be tactical and tough, and it’s likely they will be missing Harry Reid a lot.

One of Reid’s greatest skills as his party’s leader in the Senate was keeping his caucus unified. That’s a task that will be especially crucial under Trump: With ten Democratic senators from states Trump won up for reelection in 2018, the temptation for some of them to peel off and vote with Republicans — to demonstrate they can be reasonable — will be strong.

Reid engendered loyalty from Senate Democrats in several ways. One was by demonstrating that he was willing to put their interests ahead of his own. In the run-up to the 2014 midterms, when Reid was majority leader and therefore controlled the Senate calendar, he infuriated Republicans by refusing to give hundreds of bills passed by the House of Representatives votes in the Senate. “Republicans were constantly bitching about how he’d ‘broken the Senate,’ ” one Reid aide recalls. But Reid broke the Senate, this aide explains, in order to protect vulnerable Democratic senators from having to take votes that would hurt them in their reelection campaigns. “We urged him to explain publicly that that’s what he was doing,” the aide says. “But he said, ‘No, I’m trying to protect them, so I’m going to take the heat.’ ”

Reid took the heat in other ways as well — earlier this year, for instance, when Wisconsin senator Ron Johnson, a Republican, introduced legislation that would allow terminally ill patients to pursue experimental treatments when no other options were available. Dubbed the “Right to Try” bill, it seemed like an easy piece of legislation to support, but Democratic health-care wonks identified numerous problems. It indemnified drug companies and physicians from any liability arising from adverse outcomes, and it included a provision that allowed insurance companies to refuse to pay for any treatment for side effects. No Democratic senators, however, wanted to oppose the legislation themselves. So Reid did it for them — using a host of procedural maneuvers to block the legislation from receiving a vote. “It is beyond disappointing that Reid would ignore the pleas of those with terminal illnesses to score a political point,” Johnson said.

But Reid was comfortable ceding the spotlight when his colleagues wanted it. Although he had standing invitations to appear on any of the Sunday shows, he typically let Schumer or Durbin go in his place. Similarly, he frequently forfeited the traditional honor afforded the party leader of speaking first at multi-senator press events. “You’d have five senators wanting to speak at a press conference, all of them jockeying for spots,” says Rebecca Katz, Reid’s former press secretary, “and Reid would say, ‘Just take my slot.’ He’d go last. He just didn’t care about that.”

One thing Reid did care about was sticking to his guns. Once he committed to a strategy, he refused to blink. During the 2013 government shutdown — which occurred when congressional Republicans refused to pass a budget bill that did not include a provision defunding Obamacare — Republicans tried to undo the political damage by offering mini spending bills that funded popular bits and pieces of the federal government, like the NIH and national parks. Those bills passed the GOP-controlled House, but in the Senate, Reid refused to bring them to a vote. “What right did they have to pick and choose what part of government is going to be funded?” he asked. Faiz Shakir, a Reid staffer, explains, “He doesn’t let the charades deter him. When they come at him with all these little gimmicks to weaken Democrats’ resolve, he doesn’t flinch.”

Perhaps Reid’s greatest skill as the Senate Democrats’ leader was his ability to identify which fights to pick. The last time Democrats faced as bleak political prospects as they do now was in 2005: George W. Bush had just been reelected, and Republicans had increased their congressional majorities by knocking off several incumbent Democrats, including, most notably, the Senate’s top Democrat, Tom Daschle. Bush announced an ambitious plan to privatize Social Security, declaring, “I earned capital in this campaign, political capital, and now I intend to spend it.” Reid had just replaced Daschle as the Senate minority leader, and rather than kowtow to Bush, he dug in, using the Social Security battle as an opportunity to unify Democrats and strengthen their resolve. He tapped Montana senator Max Baucus — whom many Democrats were angry at for siding with Bush on tax cuts a few years earlier — to lead the fight, and he helped organize anti-privatization rallies across the country. When Bush was forced to scrap his plan, Democrats were revitalized. “He just instinctively knew that was a moment when it was time to fight,” says Shakir.

Then Reid turned to the intelligence failures that had led the U.S. into the Iraq War, which had by then become an obvious fiasco. Daschle had drawn up plans to force the Senate into a rare closed session to discuss the issue. But it was only after Reid’s ascension, and after the Social Security–privatization fight, that the plan was enacted. It was a political stunt, but a galvanizing one. “Reid just went with his gut and said, ‘We’re doing this,’ ” recalls Katz. “And it was the first time in a while that liberals saw a Democrat stand up for them.”

Had Reid decided not to retire, it’s quite possible the upcoming term would have been the most significant of his career. Trump’s claim of a mandate notwithstanding, significant parts of the GOP agenda remain unpopular, from privatizing Medicare to deregulating Wall Street. Reid would have led the fight against the president. “It would have been two guys who don’t really care about, to borrow the phrase, ‘traditional norms’ and customs going at it,” Jim Manley muses. “It really would have been something to see.”

Instead, we are about to witness the most significant term of Schumer’s career. He has already earned the allegiance of Democratic senators by naming a number of them to newly created leadership posts. (“It’s like Oprah,” jokes one Senate aide. “You get a new leadership post! And you get a new leadership post!”) And it’s likely that Schumer will hold the caucus together during the confirmation process for Trump’s nominees. Senate Democrats appear to be unanimous in their opposition to Tom Price, Trump’s choice for Health and Human Services secretary, and they hope to raise such a ruckus about Medicare during Price’s hearings that at least three Republicans decide to vote against Price, too, thus handing Democrats their first scalp of the Trump era.

According to various Senate aides, Schumer doesn’t believe his party has a chance of torpedoing any other Trump nominees, but he hopes to make their confirmations as bruising — and, with smart floor management, as prolonged — as possible. (Schumer himself declined to comment.) “The goal will be to show the public how controversial these nominations are,” explains a Senate Democratic aide. Similarly, Schumer can expect to have the unanimous support of his caucus in pushing for a select committee to investigate Russian hacking of the election, and thanks to his bringing several Republicans onboard for that effort, he’s made it more difficult (or at least more uncomfortable) for Mitch McConnell to stop them.

But those are the easy parts. The battlefield becomes more perilous for Schumer as Trump and his party move on to other parts of their agenda. Again and again, the New York senator will be faced with the question of where and how often to use intransigence as a strategy. That his primary congressional adversary will be McConnell raises the stakes further, as the Kentucky senator has proved to be an even more ruthless majority leader than Reid was before him. It was McConnell’s singular insight that, even if Republicans were responsible for the lack of bipartisanship and the resulting gridlock, it would be the party that controls the White House that takes the blame for it. This nuclear strategy won back all parts of government from a president and party that was historically popular at the time McConnell cooked up his plan. But will Democrats have the stomach to stymie Trump in the same way McConnell and his fellow Republicans blocked Obama?

Schumer has signaled that he’s open to backing Trump’s infrastructure package — in part on the merits (this country could use some infrastructure spending) and in part because it might turn off enough Republicans that Schumer will have some leverage over a president eager to get points on the board. “Infrastructure will really test how much Democrats are willing to hold out for a good deal versus any deal,” says one Senate Democratic aide. Obamacare will be another tricky fight. Schumer and the Democrats will obviously oppose any effort to repeal the health-care law, but the crucial battle won’t occur until Republicans try to replace it. Some Democrats are already dismayed that Schumer hasn’t done a better job of firming up commitments from Senate Democrats that under no conditions will they vote for an Obamacare replacement. “You’ve got to establish your leverage early and make it clear to Republicans that it’s a ‘You break it, you bought it’ situation,” explains the same aide. “If you don’t lock down Democrats on that position early, before the repeal bill passes, you leave yourself vulnerable to things developing in such a way that makes it harder for Democrats to maintain their opposition.”

And then there’s the budget. Trump has promised to increase defense spending; it’s likely he won’t propose a similar increase in domestic spending, and it’s possible he’ll actually seek cuts. Schumer will face an agonizing choice in how he tries to get Democrats to respond: Go to the mat in opposing such a budget and threaten to shut down the government — knowing full well that by doing so, Democrats will run the risk of losing seats in 2018 in the states Trump won? Or acquiesce?

“You can get talked out of each individual fight, and you can make the case that in every one of these instances, Democrats should cave under pressure and go along,” says the aide. “But if we do, we’ll have allowed Trump to have a functional first year that completely devastated Democratic priorities in the process.”

“The problem with Democrats is that we believe in legislating,” laments Jim Manley. It’s a sanctimonious thing to say. But would Democrats really vote against an Obamacare replacement — as bad as it might be — to spite Trump if by doing so they’d throw the American health-care system into crisis? Would they vote against a budget bill that slashes domestic spending if it meant shutting down the government?

Sometimes. And sometimes they won’t. The question confronting Democrats is whether Schumer will demonstrate instincts as canny as Reid’s. And when a fight is engaged, who will emerge as a leader who can see it through? “There’s no natural person,” concedes a senior Democratic staffer in the Senate. “It’s not Chuck’s nature. Both Bernie [Sanders] and Warren are more interested in shaping the party and the fights that we choose” — which means they’ll often be battling with Democrats as much as Republicans—“and Durbin has an instinct, but we’ll see how much he’s able to rally other people.” Reid, who’s reluctant to offer much advice to his fellow Democrats (at least publicly), nonetheless recognizes the urgency of the issue. “Senator Schumer — or somebody — will have to be willing on a consistent basis to say no,” Reid told me. “You know, stand up there and say, ‘I object.’ ”

Reid’s stature among Democrats grew after the election, in part because of his own performance on November 8. Although he wasn’t on the ballot, his hand-picked successor, Catherine Cortez Masto, kept his Senate seat in the Democratic column. Nevada Democrats also picked up two House seats that had been in Republican hands and regained majorities in the State Assembly and State Senate. The Silver State was one of the only bright spots for Democrats, and Reid, whose influence there was even greater than on Capitol Hill, received the lion’s share of the credit. After Democrats had basically been wiped out in Nevada in 2002, Reid undertook the Herculean task of rebuilding the party. “I wanted a strong Democratic Party, okay?” he says. “So who could I get to do that for me? I got me to do it.”

Together with a Las Vegas political operative named Rebecca Lambe, he helped Nevada Democrats create a party infrastructure — devoting significant time, effort, and (most important) money even in years when he himself wasn’t up for reelection. “The Reid Machine,” as his Nevada political operation came to be known, may be the most formidable Democratic state party in the country: On the Saturday before the most recent election, it did more than 70,000 door knocks in a state with a population of 3 million. “Not 7,000,” Reid emphasized. “Seventy thousand. That’s what the machine is.” Little wonder that in early December, as Democrats were still licking their wounds from their 2016 debacle, Lambe traveled to Washington to give a presentation to Democratic senators about what they should be doing in their states to help build their parties. She told them that, with Democrats controlling only 19 governors’ mansions, they as senators were often the most prominent (and sometimes only) Democratic statewide officeholders in their state and it was therefore their responsibility to help other Democratic candidates. She likened the Democratic senators to the Seattle Seahawks defense. “Defend every blade of grass,” Lambe told them.

And that’s not the only Monday-morning quarterbacking Reid and his team have been doing since Trump’s victory. Those close to him are quick to note that Reid had urged Clinton to tap Elizabeth Warren as her running mate — going so far as to have a team of lawyers devise a way that Warren could resign her Senate seat so that her replacement, appointed by Massachusetts’s governor, would only serve for a few months before facing a special election (which would be the Democrats’ to lose). “You think having Warren on the ticket wouldn’t have meant 70,000 more working-class white votes in Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin?” speculates a Reid adviser.

Similarly, last spring, when it was clear Bernie Sanders would lose the Democratic primary and Reid was working in concert with Clinton and Obama to ease him out of the race, he appeared to have successfully brokered the defenestration of Debbie Wasserman Schultz as Democratic National Committee chairman — a condition Sanders set for his departure — by lining up Richard Durbin to take her place. The only problem was Reid himself didn’t have the power to fire her. And neither Obama nor Clinton was ultimately willing to make the call to Wasserman Schultz themselves. “It would have been a big deal to fire her back in May, since it would have signaled to Bernie’s supporters that, ‘Hey, this is your party, too,’ ” laments the Reid adviser. “Instead, there was no positive when we did finally fire her.”

Reid insists he has no regrets about bowing out just as Democrats are getting ready to do battle with Trump. “If Hillary had won and had a Democratic majority, I would have really missed the action,” he told me one afternoon in his Capitol office, as he sat under a giant oil portrait of his favorite writer, Mark Twain. “With this, no, I’m not going to miss it.”

But in his final days in the Senate, Reid was as willing as ever to throw some haymakers. One day he was calling for FBI director James Comey’s resignation for his handling of the investigation into Hillary Clinton’s emails; the next he was accusing the Trump campaign of being “in on” Russia’s election hacking. As I spoke to him in his office that afternoon, he seemed to go out of his way to insult his opponents. He sarcastically dismissed John Barrasso, a Republican senator who helped spearhead the opposition to Obamacare, as “Doctor Barrasso, the orthopedic surgeon from Wyoming” — as if treating rotator-cuff injuries on the Great Plains wasn’t real medical work. Steve Bannon, Trump’s incoming senior White House adviser, was “a white supremacist, and if you spend a good part of your adult life being a white supremacist, it doesn’t change overnight.” As for Trump, Reid offered a comparison: “As you know, I opposed a lot of stuff that [George W.] Bush did, I think he was a really bad president, but it appears the Bush family is at least in the realm of rationality.”

Reid smiled to himself after delivering this line. But his smile quickly faded. The more he talked, the more fatigued — and muddled — he became. Although he wanted to sound the alarm about Trump, he simultaneously confessed, “It’s obvious he didn’t believe in all that stuff he talked about in the campaign.” He discounted the power of his own words. “I’m not too sure my opinion will matter much anymore,” he said, “and I understand that.” According to his friends, Reid was spoiling for his 2016 reelection campaign. He knew Republicans would be desperate to take him out, and he couldn’t wait to beat them back again. It was heartbreaking for him to acknowledge to himself that he didn’t have the stamina to endure a competitive election.

Reid now plans to split his time between his apartment in the Ritz-Carlton in Washington and his home in suburban Las Vegas and will likely join a law firm or become an adviser to one of the companies — like MGM Grand — that he so often helped as a senator. He’ll still offer advice to his old colleagues, but only if they call him. “He doesn’t want to be one of those guys who’s hanging around the Cloakroom,” Adam Jentleson says. Indeed, Reid sought and received a special waiver to have his official portrait unveiled in December, before the end of his term, so he wouldn’t have to go back to the Capitol after he retired.

Now in his office, on the eve of his departure, Reid seemed eager to already be done with things. After a lengthy conversation about his career and Trump and what Democrats needed to do next, Reid, slumping lower and lower in his chair, quickly sat up with a look of alarm. “I haven’t eaten breakfast or lunch,” he curtly informed me. “I’m about to terminate this meeting, okay?” In more ways than one, he’d had enough.

*This article appears in the December 26, 2016, issue of New York Magazine.