The Republican Party in its modern incarnation is incapable of writing a decent health-care bill, if we define “decent” to mean both some level of technical competence as well as morally decent. That inability has been clear to the party’s outside critics for many years. Republicans have fervently denied this, and probably believed their own denials. As a result they locked themselves into a course of action that forced them to propose a bill on a deadline. They seem to have realized the impossibility of the task midway through, but, unable to retreat on their commitment, they instead rushed out a plan that is shambolic and cruel.

The best indication of the quality of the plan is that it has drawn almost universal scorn from the health-care-policy community. It’s predictable that experts on the left would dislike Trumpcare. But the right seems barely any more favorable. Conservatives like Peter Suderman, Philip Klein, Bob Laszewski, and Avik Roy, who have spent years savaging Obamacare, are united in their disdain for its replacement.

The artificial role of the House GOP’s self-created deadline played a crucial role in the development of Trumpcare. After the surprising election handed them full control of government, Republicans quickly decided to capitalize on power with a pair of lightning-strike budget assaults. First, they would repeal Obamacare while delaying any consideration of its alternative, perhaps for several years. Having eliminated Obama’s health-care law — and, especially, the taxes on the affluent that helped finance it — the baseline of expected revenue would be lower. This would enable Republicans to then pass another huge tax cut later in the summer, which they could construct in a way to appear not to lose any revenue (and thus, because of arcane but important budgetary rules, be permanent). After passing their tax cut, they could leisurely set out to design a new plan to replace Obamacare.

When Republicans quickly discovered repealing Obamacare without a replacement was wildly unpopular — polling under 20 percent — they had to change strategies. The new approach would force them to pass a repeal-and-replace all at once, so Republicans in Congress could reassure voters they had something in place after taking away Obamacare. But now they had a vastly more complicated task. They had to do something very hard on a schedule that was designed to do something relatively easy. Republicans believe they need both chambers of Congress to pass a repeal and replacement of Obamacare by Easter, in order to keep the legislative schedule on track to allow for the passage of the tax cuts they crave.

Republicans apparently believed they could grab one of the many conservative plans that have floated around Washington, or perhaps patch a few of them together. They quickly encountered an insurmountable obstacle. The main challenge in drafting any health-care plan is financing it. If you want to finance health-care access to people who can’t afford it, then other people have to pay for it. This is always a challenge in politics, since Americans don’t like paying for other people to get things, but it’s a special challenge for a party that has elevated opposition to new taxes to the status of theological precept.

There seemed to be one way out of the trap. Conservative health-care wonks wanted to eliminate or cap the tax deduction for employer-sponsored health insurance. This would be a mechanism that could pass philosophical muster among the keepers of the Reaganite flame, while potentially raising the hundreds of billions of dollars needed to finance coverage in any Republican plan. But, as the conservative analyst Christopher Jacobs explained yesterday, when Republicans modeled out the effects of capping the tax deduction, it turned out to have a deadly result. Reducing the tax incentive for employer-sponsored insurance, they found, would cause businesses to dump more people out of their employer-sponsored insurance.

Not only would this be a political catastrophe — millions and millions of Americans who were covered through their work and considered themselves safe would suddenly be tossed off their plans — it was a fiscal disaster as well. These newly uninsured people would now be eligible for the tax credits Republicans were trying to provide for the people already getting insurance through Obamacare. Jacobs likened the problem to quicksand. “The more they thrashed to get out of the quicksand — by increasing the subsidies or adjusting the cap on the employer exclusion, or both — the deeper they sank,” he reported, “by increasing the erosion of employer-sponsored insurance.”

Republicans responded to this trap by giving up on their plan to cap the tax break for employer-sponsored insurance. That rescued them from their quicksand trap. But it also left them without their favorite financing mechanism. Now they had to find a way to pay for tax credits for the people they were throwing off Obamacare’s markets.

How to do that? This is where they landed, by financing Trumpcare with the one source of fiscal savings Republicans inevitably fall back upon when their fiscal plans don’t add up: poor people. Trumpcare now finances the tax credits for the uninsured primarily by cutting Medicaid. We don’t yet know whether this will add up. The Congressional Budget Office will score the bill only after it has started to move through committees in the House. If it does, it means that the Republicans will have done an astonishing thing, by financing the cost of replacing Obamacare entirely out of the budget that already financed health care for the desperately poor and sick.

And so the Republicans are left with an utterly inadequate financing source for their plan. Because of the ideological construction of their party, they have no plausible way to find more money. Indeed, the main threat to its passage through the House is that the most conservative wing of the GOP caucus considers the plan too generous. The House Freedom Caucus is threatening to oppose any bill that gives coverage subsidies to people with moderate incomes, however meager those subsidies may be.

There are other massive problems as well. Obamacare concentrates its benefits on people with the most modest incomes. Republicans would spread them much higher up the income ladder. Obamacare ties its subsidy levels to the cost of health insurance in a market. Trumpcare does not. As a result, people in high-cost areas — like rural markets — would have their subsidy cut in half or more. When you combine all these problems — a smaller overall pool of money for subsidies, and targeting the subsidies less efficiently — you have a recipe for massive harm.

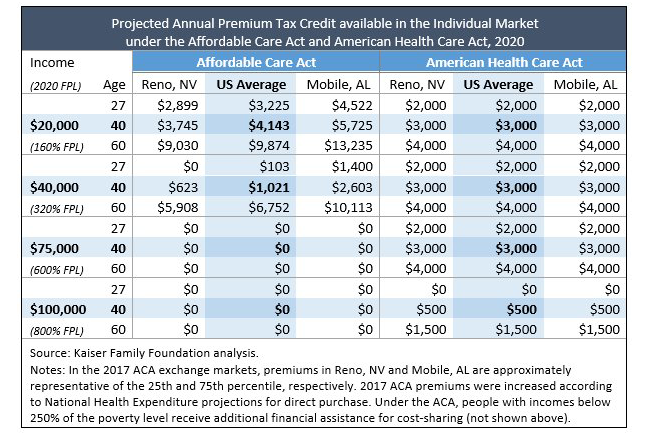

The Kaiser Family Foundation calculates the changes to customers in two sample markets: Reno, which is a cheap market, and Mobile, which is expensive. A 60-year-old in Mobile who earns $20,000 a year currently qualifies for a tax credit of $13,235 to buy insurance. Under Trumpcare, that tax credit would be reduced to $4,000 a year. On the other hand, people who earn $75,000 a year, who currently get nothing to help them buy insurance, would get a $4,000 credit from the Republican plan.

That is not the end of the problems with Trumpcare. Republicans have committed to eliminating the individual mandate to purchase insurance, which is an important component to making the law work. (If insurers can’t deny coverage to people who are sick, there needs to be an incentive to prevent people from going uninsured until they get sick and need coverage.) Keep in mind that Republicans used to consider an individual mandate uncontroversial. Conservative health care plans in the 1990s included one, and Mitt Romney encountered almost no opposition when he defended the idea during his 2008 campaign. But after Obamacare created an individual mandate, Republicans came to fixate on this provision as the plan’s most sinister provision. In part they did this because the mandate was the only portion of the plan that they could mount a halfway plausible legal case against. Conservatives went to court to eliminate the mandate and narrowly lost, in 2012.

So, because Republicans have spent years dismissing it as tyranny, Trumpcare has to eliminate the individual mandate. They came up with a different kind of penalty for going uninsured. If you go two months without coverage, then insurers are allowed to charge you 30 percent if you want to buy back into the system. Republicans may think this is a clever way to penalize people for going uninsured. It is likely to fail to accomplish its purpose, or even to backfire. People lose their coverage all the time. If you’re facing a 30 percent rate hike to get back on insurance, then your incentive changes: Now you want to wait until you really need insurance to pay those hefty premiums. In other words, rather than giving healthy people a reason to stay in the insurance pool, this gives them a reason to stay out.

In the absence of a CBO analysis, we can only guess at the effects of this bill. But the inadequacy of the subsidies, the deep cuts to Medicaid in future, and the horrible design of the insurance requirement all suggest a bill that would fail utterly to replace Obamacare. The affordability problems that hamper some markets now would explode into full-blown crises. Many markets would probably enter actuarial death spirals (which, contrary to the insistence of Republican officials, are not happening now).

The national health-care debate began in 2009. Republicans have had eight years since then to draw up and unify around a plan of their own. They have spent this time insisting they could do so easily. For most of the year, in fact, House Republicans have been running a television ad assuring the public they already “have a plan” with wonderful features: “Health insurance that provides more choices and better care, at lower costs. Provides peace of mind to people with preexisting conditions … without disrupting existing coverage.”

Eventually they had told the lie so long it became impossible for them to abandon it. And so Republicans have found themselves frantically scrawling out a hopelessly inadequate solution in order to meet a self-imposed deadline driven by their overarching desire to cut taxes for the rich. “Expanding subsidies for high earners, and cutting health coverage off from the working poor: it sounds like a left-wing caricature of mustache-twirling, top-hatted Republican fat cats,” writes the Republican health-care adviser Avik Roy. The caricature is true.