The American people are less racist than they used to be (by some measures, anyway).

In 1990, 63 percent of nonblack Americans said they would be opposed to a close relative marrying a dark-skinned individual, according to polling from Pew Research; by 2016, that figure had fallen to 14 percent. And when Americans are asked to contemplate interracial marriage as a general concept, roughly 87 percent approve, according to Gallup — up from 48 percent in 1995, and 4 percent in 1959. Meanwhile, racially and ethnically motivated hate crimes fell by nearly 50 percent between 1994 and 2015, according to FBI data.

In our popular culture and politics, nonwhites have made significant representational gains over the past three decades. And while (25 percent of adult) Americans did just elect the most overtly racist president in our modern history, that racism appears to have rendered him toxic to nearly 60 percent of the public.

But if Americans have grown less racist in recent years, their economy most certainly has not. In fact, a flurry of new research suggests that economic inequality between black and white Americans is far greater than members of either demographic realize — and will only grow larger, absent a concerted policy response.

Last week, census data revealed that median household income in the United States hit a record high in 2016 — finally eclipsing the peak it reached in 1999. This finding deserved less celebration than it received. (If you told economists in 1999 that the median American family wouldn’t see a rise for the next 16 years, even as the prices of health, housing, and higher education would all drastically increase, you would not have been called an optimist.) But when one looked to the median income of African-American households, there wasn’t even superficially good news to report: In the last year of the Obama presidency, black families were still earning less than they did in the early 2000s.

This dispiriting reality has myriad causes. But a new study by Northwestern University, Harvard, and the Institute for Social Research in Norway shines light on one of them: Employers are still discriminating against African-American job applicants like it’s 1989.

The researchers arrived at that conclusion after examining the results from every available field experiment on racial discrimination in American hiring that was conducted between 1989 and 2015. To measure the effect of racial prejudice in the hiring process, these experiments deployed either résumé tests or in-person audits. In the first case, hiring managers are presented with résumés from applicants who have nearly identical qualifications, but a diverse array of stereotypically white, black, or Latino names. In the second case, similarly qualified white and nonwhite applicants go in person to apply for a job.

In 24 such studies — together representing more than 54,000 applications submitted for more than 25,000 job openings — white applicants received, on average, 36 percent more callbacks than equally qualified African-Americans.

Critically, this average held relatively steady throughout the 26-year period when the studies were done: “In all models, we see little evidence of a reduction in hiring discrimination against African Americans over time,” the researchers write.

While the prevalence of hiring discrimination has gone unchanged since the late 1980s, the racial wealth gap has radically expanded. As Slate’s Jamelle Bouie notes:

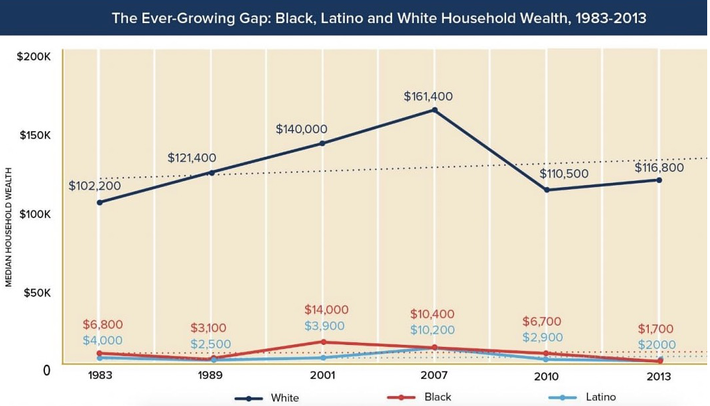

Between 1983 and 2013, according to a new report from the Institute for Policy Studies, the wealth of the median black household declined 75 percent (from $6,800 to $1,700), and the median Latino household declined 50 percent (from $4,000 to $2,000). At the same time, wealth for the median white household increased 14 percent from $102,000 to $116,800. It’s an almost unbelievable contrast, and by 2020, black and Latino households are projected to lose even more wealth: 18 percent for the former, 12 percent for the latter. After those declines, the median white household will own 86 times more wealth than its black counterpart, and 68 times more wealth than its Latino one. This isn’t a wealth gap — it’s a wealth chasm.

If nothing is done, that chasm will grow larger. By 2024, “the continued rise in racial wealth inequality between median black, Latino and white households is projected to lead White households to own 99 and 75 times more wealth than their black and Latino counterparts, respectively.”

Pew Research’s consumer survey portrays a considerably milder decline in median black net worth. Regardless, it would be difficult to overstate how thoroughly either data set undermines popular narratives about racial progress in the United States. The strengthening of taboos against overt expressions of racist sentiment in polite society, the greater representation of African-Americans in popular culture, and the election of the first black president are all vital and important gains — but none of them can compensate for a sharp decline in median black wealth. In our capitalist society, money is power. And black power is steadily diminishing.

Unfortunately, the gains that anti-racists have made in America’s cultural sphere seem to be blinding much of the country to this fact. A recent study from Yale found that even African-Americans at the bottom of the U.S. income ladder (erroneously) believe that progress is being made on economic inequality between racial groups (among wealthy whites, this belief is even more widespread).

Ever since the 2016 Democratic primary, (relatively small) factions on the American left have been squabbling about the relative merits of “identity politics” and “economic populism,” with the former term denoting a progressivism that prioritizes the elimination of disadvantages rooted in race, gender, sexual orientation, and other marginalized identities, and the latter denoting a politics that prioritizes the downward redistribution of economic power.

The findings surveyed above expose the fraudulence of this dichotomy. Racial prejudice has economic consequences. You cannot advance the cause of economic justice without addressing persistent discrimination in housing, hiring, and lending. And economic inequality has racial consequences — you cannot advance the cause of racial justice without addressing the chasm that has opened up between the wealthiest people in American society and everyone else. In fact, because centuries of de jure oppression have left African-Americans overrepresented at the bottom of our nation’s class hierarchy — and white men radically overrepresented at its top — few policies would do more to advance the cause of racial equity in the United States than ones that transfer material resources from the rich to the poor and working class. Further, there is latent potential in marshaling a cross-racial coalition for such redistribution. As this chart of the ISP’s findings demonstrates, white media- household wealth has also declined since 1989, even as the very richest white families have achieved unprecedented prosperity.

There is real value in pushing for greater diversity on television sets and in boardrooms, in stigmatizing racist dog-whistles, or in encouraging white undergraduates to contemplate their racial privilege. But if these endeavors aren’t paired with organizing around redistributive reforms, that value will be limited. American society has grown more “woke” over the past three decades — and black communities have grown evermore materially disadvantaged. To arrest that terrible trend, we’re going to need an economic theory.