Last week, Republicans in Oklahoma voted to raise taxes on fossil fuel companies, so as to increase pay for public sector workers. That might sound like a perfectly ordinary thing for a state government to do. But in Mary Fallin’s Oklahoma, it’s anything but. This is a state that responded to a $1.3 billion budget shortfall in 2016 by cutting taxes on the rich, and renewing a $470 million tax break for oil and gas companies. It’s a state that has allowed fracking interests to turn it into the earthquake capital of the world; let a gas company literally dictate policy to its attorney general; and forbade itself from raising taxes on anyone unless three-fourths of its state legislature approves (and its state legislature is dominated by tea party conservatives). All this has made increasing taxes on the state’s top industry so unthinkable to Oklahoma Republicans, they have repeatedly found it preferable to plug budget gaps by raiding their state’s emergency funds, and forcing one-fifth of its school districts to adopt four-day weeks instead.

Thus, it was more than a little remarkable when, last Thursday, Governor Fallin signed her name to a bill that more than doubled the state’s tax on fossil fuel production, limited itemized deductions for high-earning individuals, and gave a $6,000 raise to the state’s teachers.

And it was even more remarkable when said teachers responded by demanding more.

On the surface, the wave of teacher strikes that has rippled through red America over the past month looks like a labor story; an object lesson in the power of solidarity, and the hazards of underpaying workers and then leaving them no source of leverage save walking off the job. And it certainly is that kind of story — but it is also a political one. After all, public workers can only gain leverage through a strike if a significant portion of the public rallies behind their picket line. It took the fortitude of West Virginia teachers to get this strike wave started — but it required the political weakness of the GOP’s prevailing ideology to keep it rolling.

Teachers scored improbable victories in West Virginia and Oklahoma by exploiting the biggest open secret in American politics today: The Republican Party and its voters have radically different political views.

The former has made cutting taxes on the wealthy and corporations its top economic priority on both the state and federal levels; the latter oppose such tax cuts by overwhelming margins. GOP office-holders have worked tirelessly (if unsuccessfully) to reduce federal spending on health care; most GOP voters would like to see such spending increased. Nearly all House Republicans have repeatedly affirmed their support for financing ever-lower taxes on the rich with draconian cuts to public investment in virtually everything but the military, including Medicare benefits; when pollsters referenced this reality to right-leaning voters in a 2012 focus group, the respondents found Paul Ryan’s agenda so absurdly offensive, they “simply refused to believe any politician would do such a thing.”

When Republican primary voters choose a demagogue who evinced indifference to “free market” pieties — and support for massive infrastructure stimulus, universal health care, price controls on pharmaceuticals, and higher taxes on the rich — as their 2016 standard-bearer, many pundits were perplexed. But they shouldn’t have been. It would be far stranger if Republican voters really did feel a deep loyalty to the Ryan budget. After all, no mass constituency in any other advanced democracy on planet Earth has ever rallied behind such a cause. The GOP has not made support for tax cuts (no matter the economic conditions, geopolitical circumstances, or resulting consequences for social spending) the first principle of its domestic agenda because that is a popular and rational governing ideal — but because it is an excellent value proposition to offer to well-heeled reactionaries in search of a medium-risk, high-return investment opportunity.

To this point, the GOP has paid no great electoral price for the fact that there is no significant constituency for its economic agenda; over the past decade, Republicans have managed to grow more fanatically committed to fiscal policies that their voters find abhorrent — and more politically powerful. A variety of factors have abetted this odd achievement, not least the fact that most voters pay far less attention to the details of policy than to identity-based appeals. Through “culture war” rhetoric and legislation, the GOP has established itself as the party of rural Americans, cultural traditionalists, gun enthusiasts, and the (proudly) white and native-born. The broad appeal of this reactionary brand of identity politics (combined with copious Koch network cash, the right’s vast propaganda apparatus, and a touch of voter suppression) has allowed the Republican Party to have its fringe fiscal agenda, and its electoral majorities, too.

But then, it’s not that hard to get voters to prioritize the validation of their cultural resentments — over the preservation of their favorite “big government” programs — if you never actually get around to cutting the latter. At the federal level, Republicans have been able to honor their fiduciary duty to their oligarchic donors without imposing austerity on their constituents. Donald Trump tried to pay for his supply-side tax cuts by decimating Obamacare — but once doing the latter proved untenable, he and his allies were content to put the former on the nation’s credit card, just as George W. Bush had done with his tax cuts, years earlier.

But Oklahoma can’t print its own currency. On the state level, budgets have to balance. Congressional Republicans can obscure (and/or defer) the trade-offs inherent to “starving the beast” — GOP governors have no such luxury. And eight years after the tea party wave lifted far-right Republicans to unprecedented power in states all across the country, those trade-offs have become unmistakeable — especially to anyone with an investment in a (typical) red state’s public-school system.

The idea that the government has a responsibility to provide a quality K–12 education to all of its young people is among the least controversial in our politics. And yet, it is a notion that is nearly impossible to reconcile with the contemporary GOP’s theological commitment to ever-lower taxes. Talented educators must be wooed with competitive pay and benefits; textbooks must be regularly updated; curricula, revised. The disparity between the actual fiscal cost of guaranteeing universal access to a public education — and what conservative Republicans are prepared to spend on schools — is currently fueling a constitutional crisis in Kansas: The Sunflower State’s founding document requires its legislature to make “suitable provision for finance of the educational interests of the state” — a requirement that Republican legislators have routinely failed to meet, in the estimation of the Kansas Supreme Court.

In Oklahoma, West Virginia, Kentucky, and Arizona, the difficulty of reconciling our nation’s historic commitment to public education with the modern conservative project has yet to generate constitutional crises — but it did lay the groundwork for the labor crises that has captured national headlines over the past month.

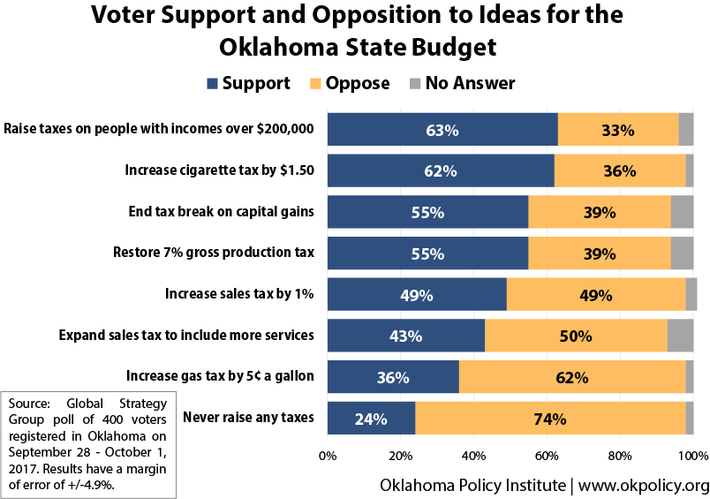

Between 2008 and 2015, per-student education spending in Kentucky fell by 11.4 percent; in Oklahoma, by 15.6; and in Arizona, by 17.5. In all of these states, Republican legislators paired such disinvestment from education with tax cuts for high-earners and business interests. Even in these “conservative” states, it is highly doubtful that voters would have ever directly endorsed supply-side tax cuts financed by reductions in school spending, were such a matter put to the ballot. But now that the former have failed to produce the miraculous growth that Republicans promised — while the latter have yielded decaying textbooks, four-day school weeks, and teacher shortages — support for a change in fiscal priorities is overwhelming in deep-red Oklahoma.

The political theorist Corey Robin has likened the red-state teachers’ strikes to California’s passage of Proposition 13 in 1978. That ballot measure gutted the state’s capacity to raise revenue through property taxes, thereby landing a body blow to “the postwar liberal settlement of high taxes, high state spending, high public services, in what had once been one of the most liberal states in the country.” This proved to be one of the opening salvos of the Reagan revolution.

It’s far from clear that this month’s red-state rebellion will be remembered as an equal but opposite harbinger (i.e., as the beginning of the end of “the era of small government”). Karma is not an operative force in American politics. A democracy dysfunctional enough to put the tea party movement into power is dysfunctional enough to keep it there. It is true that Democrats already leveraged the school-funding crisis to gain a few seats in the Oklahoma State Senate last year — but the vast majority of far-right Republican state legislators, in Oklahoma and elsewhere, have faced no penalty for defying their voters’ wishes. The fact that the unpopular consequences of right-wing governance are becoming increasingly visible in red states does not guarantee the conservative movement’s imminent collapse; but it does create an opportunity for opponents of conservatism to launch a few wrecking balls in its direction.

This is the lesson that the striking educators are teaching us. When a well-organized movement — with genuine roots in “conservative” communities (and no plausible ties to George Soros or Nancy Pelosi) forces the GOP’s fiscal agenda to the center of public debate, the political terrain shifts — and conservatives struggle to stand their ground. Suddenly, Oklahoma Republicans can vote to take money from oil companies and give it to teachers; and those teachers can meet their offer with protests instead of gratitude.