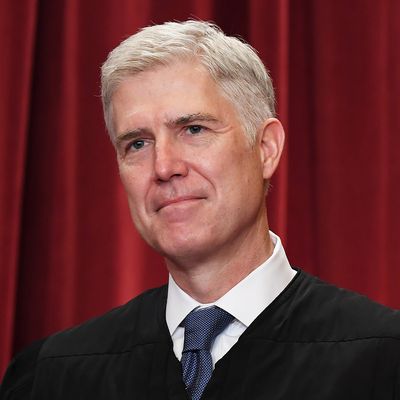

On the first day of Neil Gorsuch’s confirmation hearing, one of the stars of the show wasn’t the Supreme Court nominee, but Sheldon Whitehouse, the Rhode Island senator and member of the Senate Judiciary Committee. Looking back on the lopsided record of the Roberts court, Whitehouse felt compelled to remind Gorsuch of the legal and political reality he was about to join — one where a sizable portion of the court’s 5-to-4 rulings have gone to “distinct interests” that have prevailed over everyday people. Once he ran down the stats and the list of cases one by one, Whitehouse added: “That’s an easy 16-to-zero record for corporations against humans.”

The writing was already on the wall. With Gorsuch in the lead, a conservative majority on the Supreme Court ruled on Monday that workers who are made to sign arbitration agreements that rule out class or collective lawsuits may not then band together and rely on federal labor law to give them legal recourse to sue their employers anyway. The ruling is a devastating blow to employees who are required to sign arbitration agreements as a condition of employment — according to one report, more than 60 million workers operate under such an arrangement, which effectively forces them to resolve their disputes with their employers in a quasi-judicial hearing rather than in a court of law. Of those, about 25 million are subject to a class-action bar.

The reason you may not have heard of the case, Epic Systems Corp. v. Lewis, is that it was the very first one the high court heard back in October, on the first day of its current term — which already features enough high drama with wedding cakes, political gerrymandering, cell-phone surveillance, and Donald Trump’s travel ban, to name only a few of the pending decisions. At the heart of the dispute is the question of whether the Federal Arbitration Act, which compels enforcement of arbitration agreements, trumps the text of the historic National Labor Relations Act, a 1935 statute that transformed the workplace by allowing employees to unionize and bargain collectively for better pay and working conditions.

So high were the stakes in Epic, that during the hearing for the case — which saw lawyers for employers, workers, the Department of Justice, and the National Labor Relations Board all squaring off with everyone else — Justice Stephen Breyer openly wondered if a ruling for the employers would effectively cut out “the entire heart of the New Deal.”

That remains to be seen. And yet Epic is not such a cut-and-dry case because, on the one hand, it pits the text of two long-standing federal statutes that have nothing to do with each other, each with distinct purposes — one favoring arbitration between two willing parties, the other protecting workers who engage in “concerted activities for the purpose of … mutual aid and protection.” The employees had argued that this latter language meant that joining together to bring a class-action lawsuit effectively freed them from their contractual obligations, but Gorsuch summarily dispensed with that notion: Federal labor law “does not mention class or collective action procedures” and “does not even hint at a wish to displace the Arbitration Act — let alone accomplish that much clearly and manifestly.” Because labor law only governs things like forming a union and organizing for better wages, anything out of that ambit, like going to court as a class, doesn’t vitiate the workers’ individual arbitration agreements.

And yet the tone and tenor of Gorsuch’s opinion — which was joined by Chief Justice John Roberts and justices Anthony Kennedy, Clarence Thomas, and Samuel Alito — seemed to ignore the realities of why so many people are made to sign arbitration agreements in the first place: because they need the job and they have no real bargaining power when signing the dotted line. “The policy may be debatable but the law is clear: Congress has instructed that arbitration agreements like those before us must be enforced as written,” Gorsuch writes.

Dissenting, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and her liberal colleagues called the majority’s conclusion “egregiously wrong,” and in the process offered a brief history of labor law in the United States. In a sense, they seem to see the Epic controversy as part of a larger retreat of sorts to the Lochner years, when an activist Supreme Court was unafraid to strike down, among other things, child labor laws and other workplace protections under freedom-of-contract principles. That era is long gone, but Ginsburg wouldn’t be too far off in fearing a return to it, as some conservatives and libertarians have suggested we should. In one eye-opening footnote, Ginsburg puts the spotlight on some of the parties to this set of cases to undermine the majority’s entire premise for its ruling: that arbitration agreements are good and wholesome and statutorily sound because they’re freely negotiated between equals:

Were the ‘agreements’ genuinely bilateral? Petitioner Epic Systems Corporation e-mailed its employees an arbitration agreement requiring resolution of wage and hours claims by individual arbitration. The agreement provided that if the employees ‘continue[d] to work at Epic,’ they would ‘be deemed to have accepted th[e] Agreement.’ Ernst & Young similarly e-mailed its employees an arbitration agreement, which stated that the employees’ continued employment would indicate their assent to the agreement’s terms. Epic’s and Ernst & Young’s employees thus faced a Hobson’s choice: accept arbitration on their employer’s terms or give up their jobs.

For a conservative majority that tends to see text as supreme above all, it’s hard to see how lawmakers in 1925, when the Federal Arbitration Act was passed, had this sort of tomfoolery in mind. This disconnect between black-letter law and reality is exactly why the Epic ruling, though ostensibly correct as a matter of statutory interpretation, feels wrong as a matter of public policy and calls for course correction: Its formalism completely obviates how today’s workplace operates.

And forget about the incentives the decision provides to employers that now may feel like it’s fair game to stiff their employees. Under the Supreme Court’s pronouncement, a company that binds all its workers to submit to mandatory arbitration may one day decide to quietly and intentionally subtract $1 from each employee’s paycheck every week, just because. For one worker, one year’s worth of stolen wages would only amount to $52 — pocket change that no sensible worker, let alone one who is already struggling to make ends meet, would be willing to hire a lawyer over to recover in arbitration. But multiply that by 10,000 employees or 1 million, and it’s easy to see why banding together as a class action would make more sense.

Calling on lawmakers to fix this mess, Ginsburg, who in the past has had success turning her dissenting opinions into acts of Congress, read a version of her thoughts about Epic from the bench — the kind of thing the justices do on occasion when they’re really upset about an anomalous result. “Congressional correction of the Court’s elevation of [arbitration agreements] over workers’ rights to act in concert is urgently in order,” Ginsburg urged. Maybe Democratic majorities in Congress and in blue states will one day take her up on it.