One of the questions that always pops up after an election is whether the winning party’s coalition signals some enduring trend that ought to frighten the losing side. It’s usually wrong. As Jonathan Last points out, people were saying something like this in 2004 — Republicans had a kind of hammerlock on the hearts and souls of middle America that turned out not to exist. But I do think the larger trends point toward a future that will tilt the center of American politics leftward for quite a while. Republicans will win elections again, but the heyday of Reaganesque conservatism has probably passed for good.

Ryan Lizza has a well-timed deep dive into the GOP’s frantic, uncertain response to the rising Latino electorate in Texas, which is Ground Zero in the party’s demographic panic. Nonwhites already constitute a majority of the state’s citizens. Republicans continue to dominate because Mexican-Americans are disproportionately either too young to vote yet or not registered, but both these facts could change fairly quickly. (The Houston Chronicle and San Antonio Express-News crunch the numbers and find that Democrats are shaving five and a half percentage points off the GOP’s margin every four years, and the state is poised to turn blue in twelve years. A comprehensive campaign to register Latino voters could hasten that date.)

This poses two problems for the Republican Party. First, while the GOP’s restrictionist immigration policy has particularly alienated Latino voters, they, and nonwhites in general, have more liberal views about the role of government in general. It’s likely that Republicans could defuse some of the outright hostility felt by Hispanic voters by, say, embracing comprehensive immigration reform and putting Latinos on the national ticket. But the growth of the nonwhite electorate is such that Republicans need not just improvement among nonwhites, but continuous improvement merely to keep their head above water.

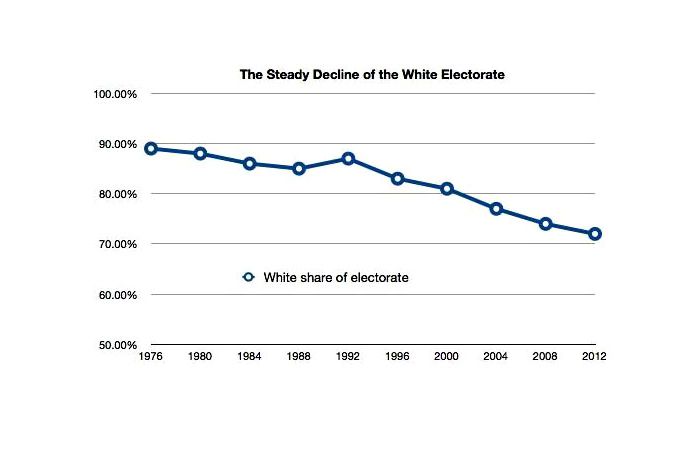

When I argued in the print magazine last February that demographic changes were working against conservatism (borrowing from Ruy Teixeira’s “Emerging Democratic Majority” thesis) conservatives like Sean Trende replied that the nonwhite vote was not especially likely to continue rising, and that Latinos might begin trending Republican. But the 2012 election shows that the decline of the white electorate, rooted in the blunt fact that whites comprise a shrinking share of the population, has not abated:

Now, the question of the changing electoral landscape has gotten tangled up in an abstruse debate about whether there is a Democratic “realignment.” The term “realignment” is a deeply contested and ultimately pointless question that has, for some reason, inspired a small library worth of books, papers, and academic conferences all debating exactly what a “realignment” means. The paradigmatic case is Franklin Roosevelt’s election, which ushered in a long period of Democratic success.

I will spare myself the furious replies from academics by stipulating there is no realignment going on. What is going on is a change, rooted mainly in demographics, that is making the traditional conservative formula obsolete. The New Deal established a positive role for the federal government in taming the excesses of the market, and the consensus was strong enough that even Republican presidents didn’t challenge it. But the politics of the New Deal began to fall apart in the mid-sixties over race, when middle-class whites began to see the Democratic agenda as transferring resources from people like themselves to undeserving blacks. The political strength of conservatism, which is not the same thing as its intellectual merits, has been its sublimated cultural appeal to white America. Starting in the mid-sixties, American politics entered a three-decade-long period of conservative dominance.

In the nineties, Bill Clinton helped Democrats to undercut the appeal of white backlash politics by repudiating racially tinged liberal positions on crime and welfare. By the end of the Clinton era, the parties had reached a rough parity. Since then, the tides have slowly been moving leftward.

There are vital caveats that I mentioned in my earlier story that bear repeating. First, short-term events can always overrule deeper climactic changes. Republicans won two presidential elections during the height of the New Deal era because they had Dwight Eisenhower (and Americans were ready for a change after twenty years of Democratic presidencies.) Democrats won victories in 1974 and 1976 because of Watergate. But Eisenhower still expanded the New Deal, and Jimmy Carter rolled back government, because each was forced to accept terms of debate dominated by the other side. Any number of potential events — a scandal, another recession — could bring the GOP roaring back in 2016.

Second, there is no such thing as a permanent change in American politics. What we’re talking about here is the landscape for a quarter-century or so — anything beyond that is too distant to project. In the long run, interracial marriage and cultural assimilation will make the descendants of today’s Latino voters identify much more closely with the white mainstream, which will make them more amenable to conservatism. But that long run is pretty far off. For the foreseeable future, the decline of the white population is occurring much more rapidly than the weakening identity of the nonwhite population. The Democrats have a party identity that is well suited to this environment; it is the Republicans who will have to adapt.