Despite some tensions with his fellow Republicans, Chris Christie is well-positioned to become the front-runner for the GOP presidential nomination in 2016. He’s poised to easily win another term as governor; he polls strongly against Hillary Clinton; and he’s successfully tapped into voter discontent about the partisanship, political posturing, and general bullshittery that plagues Washington. There’s just one problem: Christie is very overweight — so much so that one esteemed former White House physician (a Republican, in fact) is worried he could die in office.

It’s unclear whether Christie would be the heaviest president in American history, but he would certainly share one of the top two spots with William Howard Taft, who served as our 27th president from 1909 to 1913. And though that was a long time ago, in a much different era, there may be a thing or two that Christie can learn from Taft’s experience.

Perhaps the most important lesson is that Taft — who probably never got stuck in a bathtub, but did once travel to the Panama Canal with a tailor-made tub that was reportedly “the largest ever manufactured” — embraced his ample size with good humor. As David Burton writes in the foreword to a collection of Taft’s writings:

From all accounts, Taft was not overly sensitive to the weight factor, and was sometimes ragged by his friends. One of the favorite jokes when he was at the War Department went like this: Ever the gentleman, the Secretary while riding a street car gave his seat to three ladies. He took such stories in fun, such was his self-confidence.

“He took these references in stride,” Burton told Daily Intelligencer. In fact, Taft would also make jokes at his own expense. As a Yale archivist once wrote in the school’s alumni magazine:

Some of the better anecdotes relating to Taft’s great size originated with his Yale friends and associates. One of the first was told by Anson Phelps Stokes about the day in 1912 when, as Secretary of the University, he called upon Taft in the White House. “When I suggested to him,” said Stokes, “that he occupy a Chair of Law at the University, he said that he was afraid that a chair would not be adequate, but that if we could provide a Sofa of Law, it might be all right.”

Christie is actually following the Taft playbook here by, for example, eating a doughnut earlier this week on the Late Show, whose host had made approximately 4,000 “Chris Christie is fat” jokes over the past few years. But Christie also flashed some anger at Doctor Connie Mariano, the White House physician who made the dire warning about Christie’s weight. “This is just another hack who wants five minutes on TV,” Christie said yesterday. “If she wants to get on a plane and come here to New Jersey and asks me if she wants to examine me and review my medical history, I’ll have a conversation with her about that. Until that time she should shut up.”

Of course, Taft campaigned for president as an obese person in a much different environment. There were no TV images of the rotund politician beaming into voters’ homes, no YouTube to spread clips of Taft housing a corn dog in the hot sun at the Iowa State Fair. Hell, there weren’t even that many photographs, much less full-body shots. Most of all, though, obesity just wasn’t the same kind of widespread health concern that it is now. Burton tells us that Taft’s weight “never became an issue,” or at least a major one, during his presidential runs.

Nevertheless, Taft was mindful of his image during the 1908 campaign, as the University of Virginia’s Miller Center recalls:

At Nellie’s urging, Taft announced that he intended to drop thirty pounds off his 300 pound plus weight for the campaign fight ahead. He retreated to the golf course at a resort in Hot Springs, Virginia, where he stayed for much of the next three months.

Taft continued to try to get a handle on his ballooning weight as president, but his wife and his doctor seemed more invested in the effort than he was. In his memoir, Chief of Mails Ira Smith recalled Taft discovering that there was no dining car attached to his train during an overnight trip:

“Norton!” he called in a cold voice. “Mr. Norton!” Charles D. Norton, a tall, good-looking, and well-dressed man, appeared from the next compartment. He was Mr. Taft’s secretary, and he probably had been given special instructions by Mrs. Taft in regard to the President’s diet on the trip.

“Mr. Norton,” the President said, “there is no diner on this train.” Norton agreed that there was no diner. He reminded Mr. Taft that they had had dinner at the White House, and assured him that they would not go without breakfast. He recalled that the President’s doctor had warned him about eating between meals.

The President brushed him aside, turning back to the conductor. “What’s the next stop, dammit?” he asked. “The next stop where there’s a diner?” The conductor believed that would be Harrisburg.

Mr. Taft glared at Norton and addressed the conductor: “I am President of the United States, and I want a diner attached to this train at Harrisburg. I want it well stocked with food, including filet mignon. You see that we get a diner/’ He silenced the secretary’s protests with a roar. “What’s the use of being President,” he demanded, “if you can’t have a train with a diner on it?” Norton gave up. The diner was attached at Harrisburg in the middle of the night, and the President had the news papermen advised that it was open to them.

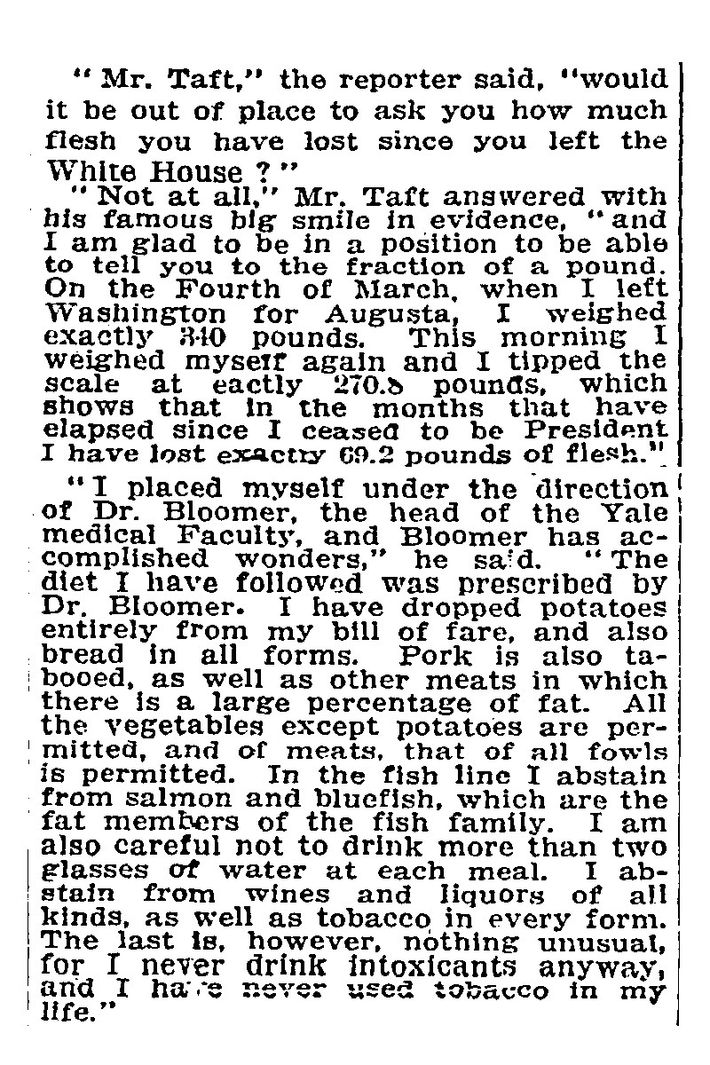

Eventually, Taft did get serious about slimming down, and he boasted of dropping “exactly 69.2 pounds of flesh” in the ten months after leaving the White House. Perhaps Christie, who is also trying to lose weight, could take a page from the Taft Diet, which the ex-president described in detail to the New York Times in the adorable parlance of 1913:

Ultimately, though, Taft’s smartest move of all was getting himself appointed as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. Those robes can hide a lot.