There are two kinds of arguments against Obamacare: technical arguments and moral ones. The technical ones take on a more moderate cast, presenting practical reasons why the law will fail to achieve its stated objections. These arguments have fared very poorly, and have been continuously discarded and replaced with newer ones as the evidence has piled up against them. The moral arguments make the more ambitious case that Obamacare is wrong, and should not exist even if it does fulfill its objectives. Since the moral case against Obamacare has limited appeal to true believers in the anti-government case, who are willing to accept deep levels of real-world pain in order to maintain their anti-statist bona-fides, conservatives tend to make it only when addressing fellow believers. (Ben Carson forthrightly made such a case in Iowa while competing for far-right support.)

The American Enterprise Institute’s Michael Strain has an essay in the Washington Post attempting to thread this needle. Strain makes a moral case against Obamacare without relying on the intractable anti-government principles usually required to make such a case. Strain’s argument has attracted a fair amount of attention, perhaps due to both its novelty and the bald callousness of its headline. (“End Obamacare, and people could die. That’s okay.”) Strain has done a lot of good work, but this piece is not an example of it.

Strain’s argument revolves around the banal fact that no society provides unlimited medical services to all its citizens. (“Liberals and conservatives agree that in a world of finite resources, some people are going to die of potentially treatable illness and injury.”) Repealing Obamacare would deprive some citizens of access to care but, hey, society has to make choices like this all the time. Few of us would have the government spend millions of dollars for an experimental treatment that may extend an old man’s life for a week.

The first problem with Strain’s argument is that it treats the banal case, that rationing medical care can be moral, as a blanket rationalization for any kind of rationing scheme. Yes, making choices about how to spend money on medicine is necessary, and those choices will lead to some otherwise preventable deaths. But suppose one policy were to deny medical care to members of one ethnic group while lavishing higher levels of care on everybody else. Would that be a scheme Strain would defend morally? Of course not. Some forms of rationing are easy to defend morally (say, limiting access to exhorbitantly priced treatments with meager or uncertain benefits). Other forms are harder to defend.

Acknowledging the possibility of a difficult moral trade-off is the start of any serious reckoning. Strain oddly treats it as though it is the end. Rather than wade into the trade-offs created by repealing Obamacare, he simply asserts the conclusion is obvious: “Repealing Obamacare could — although wouldn’t necessarily — result in more people dying. But it clearly would not be immoral.” I don’t understand how this sort of language (“it clearly would not be immoral”) could be used to defend any moral choice. Moral choices are subjective by definition. Some people believe the level of medical deprivation caused by repealing Obamacare would be moral. Some people think it would be moral to force the staff of the American Enterprise Institute to engage in gladiatorial bouts to the death for our amusement. The problem here isn’t that Strain offers the wrong answer but that he offers the wrong kind of answer.

I personally consider the kinds of trade-offs caused by repealing Obamacare wildly immoral. Repealing Obamacare does not raise questions about luxuriously expensive treatments. It raises questions about access to basic forms of care that, in my opinion, should be available to all Americans.

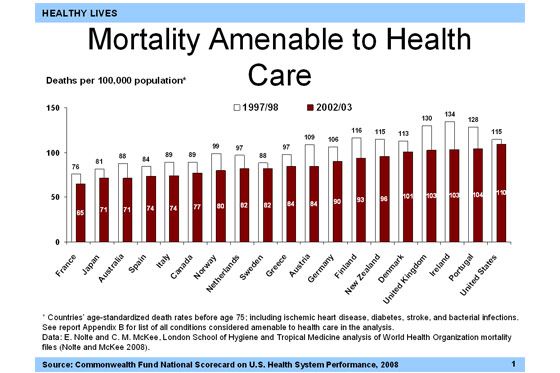

Indeed, in a column I wrote several months ago, which Strain links in his essay, I cited one of those trade-offs: David Tedrow, a 54-year-old who received a liver transplant, financed through Obamacare, which saved his life. Since the United States is the only advanced democracy that does not offer access to basic medical care to all its citizens, there are plenty of David Tedrows out there. The U.S. before Obamacare had the highest rate of preventable death in the advanced world:

Since, as noted, moral questions are subjective, Strain is free to defend a different conclusion. The trouble is that he resolutely fails to do so. The point of my column was not merely that repealing Obamacare would kill people like Tedrow, but that conservatives refuse to acknowledge the actual trade-offs embedded in the Republican Party’s health-care agenda. His essay provides yet another example of this. Strain devotes considerable space to comparing Obamacare to a hypothetical, alternative Republican health-care plan. But the explicit point of my column is that such a plan does not exist. When Obamacare came to a vote in 2010, Congress did not choose it over a Republican alternative. They chose it over a cruel, bloated status quo. Likewise, the Republican Party has held a continuous series of repeal votes and budget exercises that have repeatedly affirmed its intention to restore the pre-Obamacare system. Different Republican health plans exist in concept, of course, but none of them is or has ever been the Party’s actual alternative.

The Party’s intellectuals are playing a laudable role of encouraging it to adopt an actual health-care plan. But the price of remaining in good standing as a Republican (in contrast to David Frum, who was fired from AEI after merely questioning the Party’s legislative strategy on Obamacare) is to pretend that their hoped-for alternative is some approximation of the real thing. Strain’s piece continues the Republican reformist tradition of comparing the actually existing Democratic health-care plan against a hypothetical Republican one. And the reason is that the actual trade-offs created by the Republican health care agenda — denying millions access to basic medical care, subjecting them to pain, financial ruin, and even easily preventable death -— is impossible to defend.