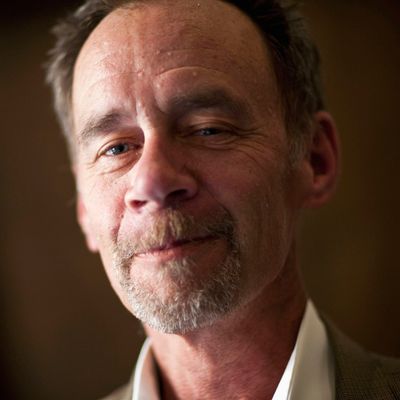

Just before going to the New York Times — which is to say, just before David Carr became David Carr — he worked at New York Magazine. He spent only a brief while with us, maybe a year, maybe less. But the idea that he’d wind up the consummate Timesman still surprised many of us at first, particularly those who adored and thought we understood him: He was a stylist, a wit, a freak who spoke in syncopated rhythms and gonzo oratory, a creature who’d led his life on the margins of journalism (at alt weeklies, start-ups, etc.) and seemed far better suited to tossing darts at big institutions than trying to blend into one. The man had shot cocaine into the veins of his hand, for heaven’s sake, and been friends with guys like Bongo and Tony the Hat. (For more details, read Night of the Gun; and David, may you see your soaring Amazon rankings in heaven — last I checked you were No. 26.) Yet somehow, as my colleague Gabe Sherman and others have noted, he became the face, and a funny one at that (neck posture of a turtle, nose and mouth as if they were experimentally rendered in left hand), of America’s hoariest newspaper, even of the media industry itself. What. The. Hell?

But maybe we shouldn’t have been so surprised. September 11 happened while he was at New York, and I remember him racing toward the center of the action when he wasn’t obliged to do so; he came back to the office late that afternoon, covered in ash. He was obsessed with the firefighters and spent days talking to them. Some of his fascination with them was doubtless the product of his working-class Irish affinities. But another piece of it, I’m guessing — though I hadn’t put it together at the time — was that he probably secretly desired to be a first responder himself. It was just in a different business.

So yes, in retrospect, the signs of the famous-guy-to-be were perhaps there all along. David was, in everyday life, the king of the aphorism — he spoke in tweets long before they were invented, and long before he got his 469K followers — and the best thing he ever wrote for New York was in fact an 18-point list of ingenious observations about post-9/11 New York that were no more than 140 characters apiece, though he expanded briefly on each of them. (My hands-down favorite: “There have always been people crying on the streets of New York. Now we know why.” And a distant second: “Evil now has an address.”)

What all of us who knew him pre-fame had failed to see is that David, who’d been off crack for years, found his new drug of choice in the Times specifically and new media more generally. He used to call cocaine “more,” back when he was still using (as in, “you got any more?”), and this he replaced with an almost epic stream of tweets (30K, according to his account). He wrote thousands of words per week for the Times and responded to almost every email he got (which he conceded to me in a 2008 profile was certainly excessive, but also probably a compulsion: “Like if I don’t, flying monkeys will attack”). He loved the power the Times gave him, in much the same way, I’m guessing, that he loved the sense of omnipotence that crack made him feel. (He described his fondness for this feeling with shocking candor in Night of the Gun.) When he left New York, he said it was because he wanted the juice. He knew that if the New York Times were his last name (his words, as in, “It’s David Carr calling from the New York Times”), people would quickly answer.

And it did juice him. At the Times, he turned into a supersize version of himself — a Macy’s Thanksgiving Day balloon hovering above the city with a combination of menace and vigilance, audacity and playfulness (David’s personal email handle was Carr2n, which — go ahead, sound it out — is “cartoon”). He was, at once, both harder and easier to recognize.

But what I will remember about David, as I think a lot of us here at New York Magazine will, is who he was before the media celebrity. Those who knew the before David saw and loved a man who was still trying to find his footing in New York, who told long and hilarious stories without deadline pressures looming. His most engaging insights back then would spend days — weeks, even! — as spoken-word phenomena before they saw print. (He liked to walk around the office, for example, reassuring the jittery that the most deadly spore in New York wasn’t anthrax but fear, which had a much more calming effect in person than it did in print, though it consoled there too.) His genius and oddball way of talking, his screwball combination of bluster and generosity, his fanatical loyalty (to friends, to his wife Jill, to his three amazing girls) were qualities his friends and colleagues selfishly got to enjoy.

There came a moment after September 11 when I told David how sad and afraid I was to be single. This was a risky confession: David wasn’t much for whining; he believed in toughing it out, in stoically bearing life’s hard knocks. But I was lonely, scared, and horrified to discover — as so many unmarried people were back then — that if the world came to an end, no one would check in on me besides my parents, and that I myself would have no one to phone. A few minutes later, he shot me an email. It had all his phone numbers in it, and he demanded mine. You will not, he assured me, ever be alone if something like this happens again. I think of this a lot, 13-plus years later, now that I have a family of my own. The simple, straightforward kindness of it. That David was, for all of his swagger, a nurturing soul.

Many of us at New York followed David on Twitter, and today, if we look, it still says he’s following us back: “You follow each other.” How lovely it’d be if this were still true.