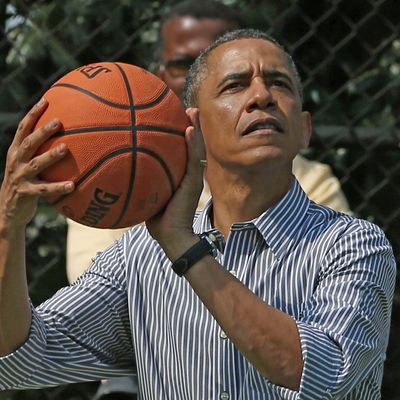

Having previously urged the NCAA to create a playoff system for football, which it did, President Obama is now following up with some proposals to change college basketball. His ideas are not good. “I am an advocate, by the way, for the NCAA changing the rules in terms of shortening the shot clock, widening the lane, moving the three-point line back a little bit,” Obama tells ESPN. “The fact of the matter is I like how basketball is going in the NBA because it’s fluid.”

These ideas have circulated around the sports commentariat over the last year or two. The problem they purport to address is that scoring is down in college basketball. Shortening the shot clock is an idea that may or may not help solve the problem it identifies. It will discourage teams from swinging the ball pointlessly around the perimeter and waiting to initiate their offense. On the other hand, some teams actually use the whole 35 seconds to try to work for open shots, and a shorter shot clock would lead to more chucking up low percentage shots as the clock dwindles.

The truly awful idea is moving back the three-point line. This bizarre idea has somehow gained strong popularity among sports pundits. This is obviously a counterintuitive way to increase scoring. The farther away the three-point line is, the harder it will be to make three-point shots, and thus the less teams will score. Yet advocates of this odd change believe that it will increase scoring by spacing the players farther apart. If three-point shooters have to set up farther from the basket, there will be more space to pass and drive.

The problem with this theory is that it’s already legal to take deeper three-point shots. There’s no rule requiring three point shooters to stand right on the line. If it’s to the offense’s advantage to take a deeper three-point shot, it can do this already. Indeed, players do this all the time. To believe that moving back the three-point line would increase scoring, you have to presume that there’s an available strategy to increase scoring and every coach in America is ignoring it.

The actual constraints on this are the limited number of players who can make NBA-range three-pointers at an acceptably high percentage. Advocates of moving back the three-point line seem to have in mind a vague idea that requiring longer three-point shots will somehow increase the supply of effective long-range shooters, but it makes about as much sense as arguing that raising the height of the rim will lead to more dunking.

If you want to increase college-basketball scoring, the way to do it is through officiating. Two years ago, the NCAA declared a rules-enforcement change to allow more freedom of movement by offensive players, by treating the constant low-level bumping and hand-checking as fouls. The coaches who had emphasized physical defense complained bitterly, and officials proved unwilling to stick to their announced plan long enough to force physical defenses to change their strategy. (Indeed, studies have shown that NCAA referees tend to balance out foul differentials, which allows physical defenses to follow a strategy of committing marginal fouls all game long until the officials get tired of calling them.) If you want a free-flowing game, the remedy is to not allow defenders to block players from moving freely. The longer three-point line is a fantasy.