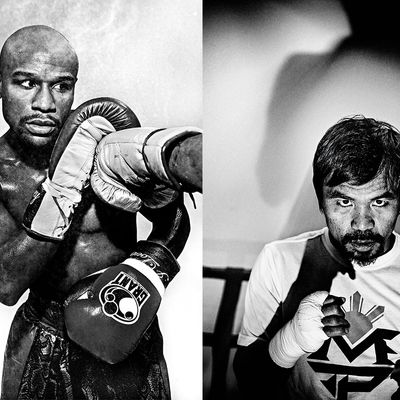

We like Emanuel Pacquiao because he is small. We admire him because he will tuck his head and duck inside the dangerous space made by a much larger man, where he will punch upward, like a deranged songbird pecking away at a cat. We like Manny because this situation reminds us of his childhood, wherein a backwoods Filipino boy, so poor he sometimes survived on a single meal a day, stole away for the city, where he punched other children for pennies. We like him because now, when he goes back home, he receives long lines of his hungry countrymen like a generous king. He pays their bills. He builds them hospitals.

Japanese fans can tell you about the time the boxer’s lout of a father ate Manny’s dog. Mexican admirers can tell you about the time when, too slim for a fight, Manny made weight by putting rocks in his pockets. On the streets of Manila, fans recognize not just the boxer but the men necessary to the boxer, such as his fast-talking, Parkinson’s-afflicted trainer, Freddie Roach, who can draw a thousand people to a mall. In a documentary about Pacquiao released earlier this year, we watch the boxer slam his fist into various faces in slow motion, while a deadly serious Liam Neeson explains that he is doing it all for us. Adds the British journalist Gareth Davies: “It’s almost as if you feel the light of God behind him.”

Pacquiao is the most famous resident of an entire Pacific nation, which, in the midst of his fights, experiences a drop in the crime rate and an unofficial truce in the war-torn south. When tropical storm Sendong hit Mindanao in 2011, attention turned to “the single biggest one-man charity institution in the country,” in the words of the Philippine Daily Inquirer: How much would he give? He has been elected twice to his country’s congress, is widely expected to run for president when he retires, and when he competes on May 2, he will be watched by 107 million Filipinos.

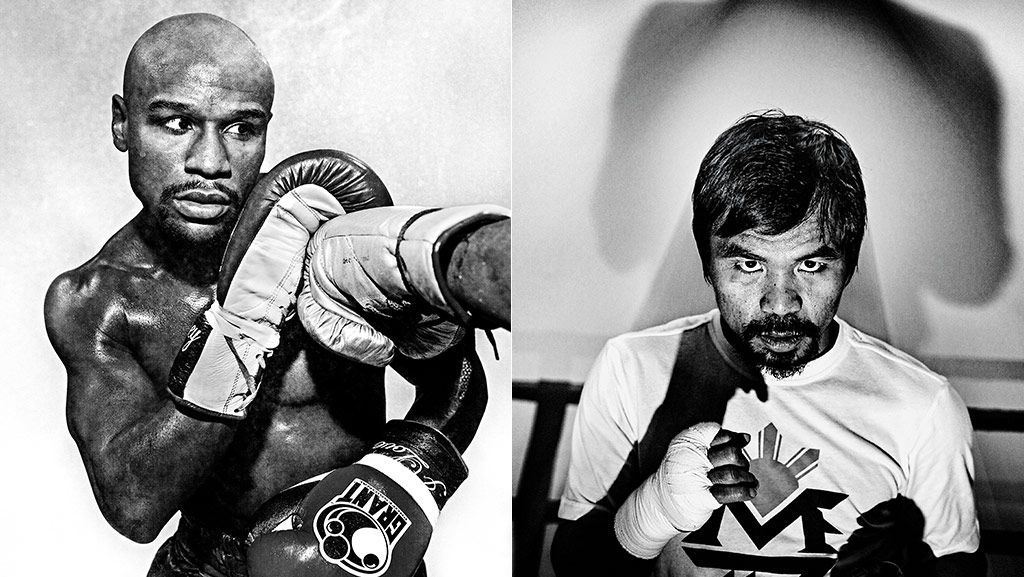

Boxing is a sport that tends toward Manichaean clarity (think Evander Holyfield versus the man who would bite off his ear), and the upcoming fight provides a suitably menacing double: Floyd Mayweather, a hermetic megalomaniac nicknamed “Money” and fond of selfies involving stacks of it, a man who spent two months in jail for punching his ex-girlfriend in the head, who demanded that his Filipino opposition “make me a sushi roll.” Money Mayweather is also the undefeated fighter slightly favored by oddsmakers, which means he fails to elicit even the sympathy that redounds to an underdog.

The Man With the Light of God Behind Him is not known for sound financial management — he is being investigated by the Filipino and American tax authorities for many millions in alleged unpaid taxes — but this fight will pay for a lot of bad decisions. The pot, an estimated $200 million, will make next month’s fight at the MGM Grand Garden Arena in Las Vegas the “richest ever single occasion in sport,” as the Guardian put it, with the cheapest seats selling for $1,500.

It’s a price set, in part, by years of anticipation and the dysfunction of the sport itself. For half a decade, Pacquiao and Mayweather, the best boxers in the world, have failed to face one another because they could not come to an agreement about the terms, or perhaps because neither ever really wanted to come to one. Days before the fight was finally announced, sportswriters were still claiming that only credulous fools could believe it would happen. It was late 2009 when HBO Sports president Ross Greenburg pointed out that a Pacquiao-Mayweather matchup would showcase “the two best pound-for-pound fighters in the world, both in their prime, in the same weight class.” It was 2010 when Snoop Dogg publicly begged Pacquiao to “get in the motherfucking ring.” It was 2011 when Nelson Mandela’s daughter tried to arrange the bout for her father’s 93rd birthday. In the interim, Pacquiao won his second congressional race and lost two boxing matches that seemed to signal the end of his best years. Repeatedly, a bout with Mayweather seemed imminent, only to collapse for reasons that were themselves the subject of dispute. Today, Pacquiao is 36 and Mayweather is 38. Both men have slowed, faded, but no one seems to care. It is simply the biggest fight in decades.

On a Thursday afternoon in March, Pacquiao, his 50-man entourage, and I fill a one-room Thai place adjacent to Hollywood’s Wild Card gym, the same joint he hits every day after training. Pacquiao is actively ignoring a plate of chicken and broccoli placed in front of him by his manager, Mike Koncz. In a couple of months, Pacquiao will be taking punches from a 147-pound man, and because he is, now, nowhere near 147 pounds, it is important to Koncz, a 50-something Canadian who has somehow earned Pacquiao’s trust, that the boxer assimilate the chicken and broccoli. Koncz unwraps Pacquiao’s napkin and polishes the fork and spoon therein. He instructs me not to ask Pacquiao a single question for the next 20 minutes. He positions the silverware beside the plate, and hopes.

But Pacquiao already has his Bible out. It is well worn and dense with pink highlighting. “Watch out that no one deceives you,” he says to a man sitting beside him. He is lecturing excitedly in Tagalog, a language he speaks with an accent educated Filipinos read as lower class. I ask Koncz about the man being lectured. “Some guy he met at Bible study,” says Koncz, sighing.

Pacquiao has a mop of black hair, a broad nose, and a wide mouth that shifts between the professional, public-ready grin and a warm smile. “Ahhhhhhhhhh,” he says, in the exaggerated way of a teacher mimicking epiphany.

Koncz asks me to push the plate of chicken and broccoli closer to Pacquiao. I give it a nudge. Koncz, evidently unhappy with my nudge, reaches past me to nudge it further. Pacquiao does not notice. Now he is shouting across the room to another table full of men in his entourage. “God made man,” he shouts, “in his image!”

Sportswriters talk constantly of “focus,” “dedication,” and “single-mindedness.” It is a measure of this cliché’s persistence that, despite the mountains of evidence to the contrary, men still use these words to describe Manny Pacquiao. This is a boxer who sidelines as a working politician and a low-budget-movie star, a man who leads Bible study on Sundays and moonlights as one of the shortest professional basketball players in the Philippines. He has recorded two platinum albums, and a hit single called “Sometimes When We Touch,” which Pacquiao admirers delicately call “sincere.” His American handlers worry that he will not eat enough, that he will not make it back to the gym, that his Filipino entourage is stealing him blind. They worry that he will fire them.

Koncz stares at Pacquiao’s chicken, willing it into his mouth. Finally, after an extended exegesis of John 1:12, Pacquiao pauses. He looks at his plate. His hand touches his fork. But his eyes wander; he notes, across the table, my empty plate. “Why doesn’t she have food?” he asks Koncz. Then, sternly, before I can protest: “Be compassionate.” He turns a Bible page. Koncz relents, and serves me.

Nearly three years ago, a boxer named Juan Manuel Marquez caught Pacquiao with a short right hand. Pacquiao pitched forward, stiff as a falling log, and stayed asleep for over a minute. When he finally came to, surrounded by cameras, it wasn’t God he called for, or Freddie Roach, but a childhood friend. “Boy nasan ka?” he asked. “Buboy, where are you?” Buboy Fernandez, a baby-faced marshmallow of a man, was cradling Pacquiao’s head in his arms. He had run from his corner and turned Pacquiao over. Crying, he reached into Pacquiao’s mouth and pulled out his mouth guard. Is the fight over? Fernandez told him that it was.

Pacquiao is not an easy person to know: difficult, unpredictable, often churlish, given to answer direct questions with either religious platitudes or monosyllabic nonresponses. Will he win this fight? His eyes dart back and forth. “If God wants.” How is he different from the way he was five years ago? He stares at his hands, flexing and stretching his fingers. “I became a Christian.” What does he want for his kids? “That they will serve God.” On television he smiles through the silence, lets sportscasters fill the spaces in between. Even when he sticks to monosyllables, the syllable he gives can be the wrong one. Are you more comfortable here or in the Philippines? “Here,” says Pacquiao, which is an extraordinary thing for a sitting congressperson to say of a foreign country.

Given his distaste for direct questions, Pacquiao relies heavily on Fernandez, and by extension the rest of the entourage. But his is not the kind of entourage that looks anything like the fairly terrifying pack of men assembled by, say, Mayweather. Money steps off his private jet and in his wake walk half a dozen admirers, black and white, barrel-chested, each taller than he is. Pacquiao’s entourage includes one Jack Russell (“PacMan”) and at least two dozen stubby-legged, middle-aged Filipino men. They walk in front and behind and to the side of their man, potbellies preceding them, gesturing with their hands. Their fat arms brush one another. They get tangled in PacMan’s leash.

On a Saturday morning at Wild Card, Pacquiao’s men laze about the gym, limbs splayed over exercise balls, backs against the ring. I ask Marvin Somodio, Roach’s Filipino assistant, where they would work if not for Pacquiao, and he laughs out loud: “They wouldn’t have jobs. Manny gives them jobs.” For the most part, the men say otherwise. Warren Tojong, who describes himself as “head of security,” used to be a police officer. JoJo Stateresa, who also describes himself as “head of security,” used to be a security guard. Noel Lautenco used to install water-filtration systems, but ever since his brother-in-law introduced him to Pacquiao, he has been in charge of PacMan. Tom Falgui is Pacquiao’s lawyer and unofficial political adviser; on the way to the gym this morning, they were discussing the recent arrest of a Muslim rebel commander. Absent today is a man known in the Philippines as Pambansang Anino, or “National Shadow.” In photo after photo, he appears as a serious, fist-pumping, squareheaded gentleman, inches away from Pacquiao’s face. When I ask Fernandez what that guy’s job is, he just shakes his head.

Fernandez sits beside a second assistant, Neri, who is in charge of cooking and wakes at 4:30 to make breakfast. Neri has two assistants, whom he calls “special children.” “They make him lose his mind,” Fernandez explains.

When Pacquiao was 16 and Fernandez was 21, the boxer had found his calling, but Fernandez was a school dropout and headed nowhere. Pacquiao made it his business to find his friend employment, hooking him up with a job as a janitor at the Manila gym where Pacquiao trained. Fernandez had no real interest in the sport. “Boxing,” he says, “was not my heart.” It took two years for Pacquiao to demand that Fernandez put on some pads and mitts. He was going to practice striking.

“I said no,” Fernandez recalls. “I cannot sustain the pain.” But Pacquiao pushed. “If you listen to me,” he said, “you will become a trainer someday.” Today, Fernandez trains at a gym back home, called PacMan Wild Card. No one bothered to ask Roach for use of the name, but the trainer is not complaining. Without Buboy, Roach would struggle to steady Pacquiao, to know when he is hurting, to deal with his superstitions, such as the idea that giving blood is enervating and drinking anything colder than body temperature is dangerous. Fernandez knows that Pacquiao needs, after a weigh-in, beef broth and warm milk.

“Every time he moves his eyes I know what he wants,” says Fernandez. “He’s like a baby. How you treat your baby, I the same treat to him. Every time when he sleeps at night, I do his hair.” Fernandez smooths his hair. “His nose.” He massages his nose.

“His legs.”

When Oscar de la Hoya was looking for a fight in 2008, he sought a rematch with Mayweather, who took himself out of contention by temporarily retiring, then approached Ricky Hatton, who declined. Pacquiao was the third choice, likely because the size disparity — four inches in height, six in reach — was so large that the bout read as a joke until the moment it began. From the first round, Pacquiao seemed to exist in a different dimension from De La Hoya, moving at one-and-a-half speed. He extends his left arm and right leg, snaps it all back in a blink, ducks, and snaps off two more jabs. Punches come from every direction, and they land. De La Hoya is knowable; we watch him set up strikes, positioning his hips, balancing as he thinks through his next move. Pacquiao’s strikes gather invisibly and emerge from all sides: a lobbing hook to the ear, a swooping uppercut to the chin.

“This is getting embarrassing,” an HBO announcer says in the fourth round. By the eighth, De La Hoya gives up, and millions of Americans have learned to pronounce the name: Pack-ee-ow.

A southpaw, Pacquiao is what is called a “high-volume puncher,” known for a combination of speed and power. Beyond this trick of balance, there is the sheer unpredictability of a Pacquiao onslaught, the ability to conjure a strike without all of the small, telling movements that make that strike possible. It was Roach who taught Pacquiao to stop leaning so hard on his left hand, but it’s still the left we watch and wait for, the arm that carries “knockout power.” That’s the arm on which you can read the names of Pacquiao’s wife and four of his children: Jimuel, Michael, Princess, Queen. There’s also Israel, whom he hasn’t gotten around to adding, and Emman, whom he never will.

According to Emman’s mother, Joanna Rose Bacosa, she met Pacquiao while working as a receptionist at a hotel in Manila. She claims that he was “extremely pleased” to hear she was pregnant and persuaded her to quit her job. He paid her maternity bills when she gave birth in 2004, and was “beside himself with joy” to find it was a boy, until, she claims, he cut them off without explanation. She also claims that he threatened to kidnap the child if she did not keep his paternity quiet. Bacosa filed a lawsuit in 2006, including in her statement a posed, smiling family photo of herself, Pacquiao, and a small boy with Pacquiao’s wide mouth.

“I am asking permission to keep my silence,” reads Pacquiao’s bizarre counter-affidavit, which hints at an affair but complains about the complaint. “If I really am the father of the child, I have given more than enough financial support to her … It’s as if they don’t know that this complaint brings with it problems to a boxer’s career.”

That was approximately the position of the Philippine president’s husband, First Gentleman Jose Miguel Arroyo, before the case was dismissed for lack of evidence. “Why are they doing this to Manny?” he asked in a television interview. “Instead of honoring and protecting him, why are they destroying him?”

This plea for self-censorship is a savvy one, in that Pacquiao’s relationship to silence has been unusually profitable for a man of such celebrity. Where there are holes in his story, we tend to fill them with assumptions of naïveté and good intentions. His political will is not a desire for power but a desire to lift the poor. His massive tax irregularities are attributed not to avarice but innocence. His win over De La Hoya is due to skill, heart, and pure Rocky-esque grit, not the fact that De La Hoya, who struggles with addiction, later admitted to drinking during training camp. Better not to dwell on the Philippine experience with celebrity governance, which has not gone particularly well.

Freddie Roach says he has seen Pacquiao angry twice in his life. Once, Roach spoke to him about playing darts late into the night, and Pacquiao gave him the silent treatment for five days. Another time, Pacquiao had just weighed in, and Fernandez brought him his beef broth. “He forgot the warm milk,” Roach says, “and Manny slapped him right in the face.”

Much of the business of the Wild Card Gym today turns on waiting for Manny Pacquiao to show up. An ever-present, wary-looking man named Rob Peters (“head of security”) watches the door. Roach leans on the ring, arms crossed, and lets the ropes carry his weight. A camera crew from HBO sets up cameras.

The television reporters were told two o’clock; it’s three now. “We’re hoping for an hour with Manny,” says a reporter. Fred Sternburg, Manny’s publicist, says “maybe” and shoots me a look of extreme skepticism.

Half of Sternburg’s job involves telling those promised time with Pacquiao by friends of friends of friends that these people have no authority to promise anything. Sternburg calls them “ventriloquists.” Just this week, he had to tell ESPN that the alleged interview opportunity arranged by “Manny Pacquiao’s business manager” bore no relation to Pacquiao’s actual schedule.

Even when the promise is made with Pacquiao’s support, his handlers struggle. Five years ago, Pacquiao was scheduled to sing a duet with Will Ferrell on Jimmy Kimmel Live. “Manny doesn’t want to do it,” Koncz told Sternburg about an hour before showtime, when they were still in the gym and Pacquiao was deep into a set of sit-ups. Sternburg laughed, assuming that Koncz was joking.

“You can’t do this,” he told Pacquiao, mid-sit-up.

“I’m not doing the singing,” said Pacquiao. “I really don’t want to do it.”

When Pacquiao arrived at the studio, a producer separated the boxer from the group and led him straight to a waiting Will Ferrell. Pacquiao relented, and by the time Koncz saw the boxer again, he was deep into the second verse of John Lennon’s “Imagine.” A strange moment in the history of late night had begun.

In what Kimmel introduces as “a special night for lovers of music,” Will Ferrell, head to toe in white, croons: “Imagine all the people.” He is playing the character we have come to expect of him, that mixture of neediness, megalomania, and earnest self-regard. Pacquiao slaps his knee and looks into the distance; he appears to be actually imagining all of the people. In his thin, soft voice, sliding in and out of pitch, utterly without irony, he sings: “Imagine there’s no country.” One can read this performance as that of a sincere and introverted man, more comfortable opening his mouth to sing other people’s words than producing any of his own, too innocent for his cynical surroundings. One might also see a man, expert at violence, surrounded by yes-men, preposterously overconfident about his capacity to conquer other realms. The failure to differentiate between abilities we have and those we do not is a quality we associate with children, and also with despots. Manny Pacquiao is the kind of extraordinarily generous person who will, at a casual lunch, take it upon himself to interpret the word of God for 50 men who have started following him around.

At 4:20, Noel Lautenco arrives with PacMan, a sign that Pacquiao is finally here. The boxer sweeps in a moment later in a starched pink collared shirt. He sits down as the camera crew sets lamps behind him. The reporter attempts to draw him out. What will he do the day of the fight? How will he prepare?

“The day of the fight I will be excited,” he says.

Does he have any special feelings about Mayweather? How does it feel to be the underdog?

“I’m not hate him.”

He stands up minutes later, and the camera crew announces that it will need some B-roll of Pacquiao shadowboxing.

“They need some B-roll,” Koncz tells Pacquiao.

“I forgot to tell you,” says Roach, “they need 15 minutes of B-roll.”

Pacquiao looks straight at Koncz, then at Roach. His face doesn’t move, but he appears to be listening. The reporters discuss the shots they need, where the light is. Roach is drawn into conversation. They are all abuzz with cinematic vision.

“Wrap your hands,” Roach says a moment later to no one, because Manny Pacquiao has left the gym.

The crowd pushes open the gym door into the bright afternoon light. Pacquiao is walking toward the Thai restaurant, his back to us. To his left is Fernandez; to his right Neri. He lifts both arms straight, on the shoulders of his men. No one will miss the B-roll. When the interview runs, all the awkward silences will be sliced out, the light will come from behind, and Manny will smile, laugh, and say nothing in particular.

*This article appears in the April 20, 2015 issue of New York Magazine.