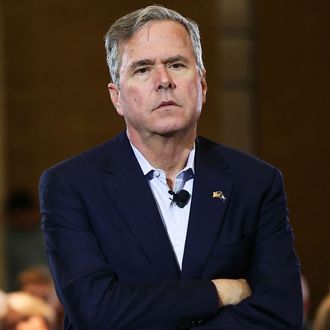

One byproduct of Jeb Bush’s long, agonizing slide out of the 2016 presidential race is that, by the time he finally packed it in this weekend, plenty of postmortems had almost certainly been prewritten. Particularly thorough autopsies were offered yesterday by the Washington Post’s O’Keefe, Balz, and Gold and by Politico’s Eli Stokols. The WaPo team emphasizes the wide gap between Jeb’s strategy and the mood of the Republican electorate, which wasn’t much looking for the best résumé and did not consider the Bush brand a plus. The Politico take is congruent, with, as one might expect, more insider details, including many fingers pointed at Sally Bradshaw, the longtime Jeb confidante who, they say, was unwilling to change the campaign’s approach despite bright-red flashing signs that it wasn’t working.

But the more basic mistake that comes out in both accounts and cannot be shrugged off as a terrible accident that befell Jeb Bush was the belief — rooted in both the public-science and punditry wings of the conventional-wisdom industry — . By the time the Bush campaign finally deigned to spend serious portions of its resources on voter communications, the candidate had already been defined by his opponents, especially the loudmouth all the smart people were writing off as an ephemeral distraction.

Team Bush’s attitude was publicly articulated by the candidate himself last September, as his public standing began its steady decline:

Former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush, who has persistently trailed Donald Trump and Ben Carson in the Republican presidential polls, is questioning the accuracy of them showing him way behind.

“These polls really don’t matter,” Bush said in an interview on “Fox News Sunday.” “They don’t filter out the people that aren’t going to vote. It’s just … an obsession, because it kind of frames the debate for people for that week.”

A month later, as donor grumbling became loud enough to penetrate even the most insular campaign, the guy handling all of Jeb’s money, Right to Rise super-pac director and alleged strategic genius Mike Murphy, granted an unusual two-part interview to Bloomberg’s Sasha Issenberg. It was designed to shame into silence anyone who’d been stupid enough to pay attention to anything that had happened thus far. Murphy described Donald Trump as a “zombie front-runner” doomed to fade into irrelevance when voters tuned in, got their signals from elites, and thrilled to the rich symphony of Jeb’s philosophy, record, biography, and electable message.

The irony, of course, is that by October of 2015 the term “zombie” best described the Bush campaign itself, pouring tens of millions of dollars a week into ads that did almost nothing. Jeb’s eleven-day reprieve from the political grave between the New Hampshire and South Carolina primaries, created almost entirely by Marco Rubio’s debate stumble in Bush’s very best state, was like the scene in a zombie movie when the objectively dead ex-human lurches forward one last time in search of innocent flesh.

In this respect, Stokols’s account of a campaign that couldn’t or wouldn’t adjust to a political environment radically different from the one it anticipated rings true, whether you want to blame Bradshaw or Murphy or Bush himself. Future candidates, however, should go to school not just on Team Bush’s misanalysis of the mood of the Republican base but also on its mistaken reliance on the many, many smart people telling us all that we can safely ignore what’s happening on the campaign trail or in the polls early on. To the incessantly cited examples of Rudy Giuliani in 2008 and Herman Cain in 2012 showing that early poll leads are meaningless, we can now add the counter-examples of Donald Trump and Jeb Bush in this cycle. Trump passed Bush in national and early-state primary polls in July 2015 and never looked back. Turns out that Jeb’s “Don’t fire ‘til you see the whites of their eyes” philosophy left his flank open and exposed. And if there is one thing we have learned about Donald Trump, it’s that when he sees a weakness in an opponent, he moves on it.