Hillary Clinton’s Campaign Was Never Going to Be Easy. But Did It Have to Get This Hard?

This is not a simple candidacy — or candidate.

In a locker room at the University of Bridgeport in Connecticut, people are waiting in line to get their pictures taken with Hillary Clinton before a rally in the school’s gym. It’s a kid-heavy crowd, and Clinton has been chatting easily with them.

But soon there’s only one family left and the mood shifts. Francine and David Wheeler are there with their 13-year-old son, Nate, and his 17-month-old brother, Matty, who’s scrambling around on the floor. They carry a stack of photographs of their other son, Benjamin, who was killed at Sandy Hook Elementary School in 2012, when he was 6. David presses the photos of his dead son on Clinton with the urgency of a parent desperate to keep other parents from having to show politicians pictures of their dead 6-year-olds.

Leaning in toward Wheeler as if they are colleagues mapping out a strategy, Clinton speaks in a voice that is low and serious. “We have to be as organized and focused as they are to beat them and undermine them,” she says. “We are going to be relentless and determined and focused … They are experts at scaring people, telling them, ‘They’re going to take your guns’ … We need the same level of intensity. Intensity is more important than numbers.” Clinton tells Wheeler that she has already discussed gun control with Chuck Schumer, who will likely be leading the Senate Democrats in 2017; she talks about the differences between state and federal law and between regulatory and legislative fixes, and describes the Supreme Court’s 2008 ruling in District of Columbia v. Heller, which extended the protections of the Second Amendment, as “a terrible decision.” She is practically swelling, Hulk-like, with her desire to describe to this family how she’s going to solve the problem of gun violence, even though it is clear that their real problem — the absence of their middle child — is unsolvable. When Matty grabs the front of his diaper, Clinton laughs, suggesting that he either needs a change or is pretending to be a baseball player. She is warm, present, engaged, but not sappy. For Clinton, the highest act of emotional respect is perhaps to find something to do, not just something to say. “I’m going to do everything I can,” she tells Wheeler. “Everything I can.”

After the family leaves the room, Clinton and her team move quietly down the long hall toward the gym. As they walk, Clinton wordlessly hands her aide Huma Abedin a postcard of Benjamin Wheeler, making eye contact to ensure that Abedin looks at the boy’s face before putting the card in her bag. The group pauses at the entrance of the gym, where 1,200 people are warmed up and screaming for Hillary. Clinton turns to me unexpectedly, and I mutter, “I don’t know how you do that … ”

“Yeah,” she says, looking right at me. “It’s really hard.”

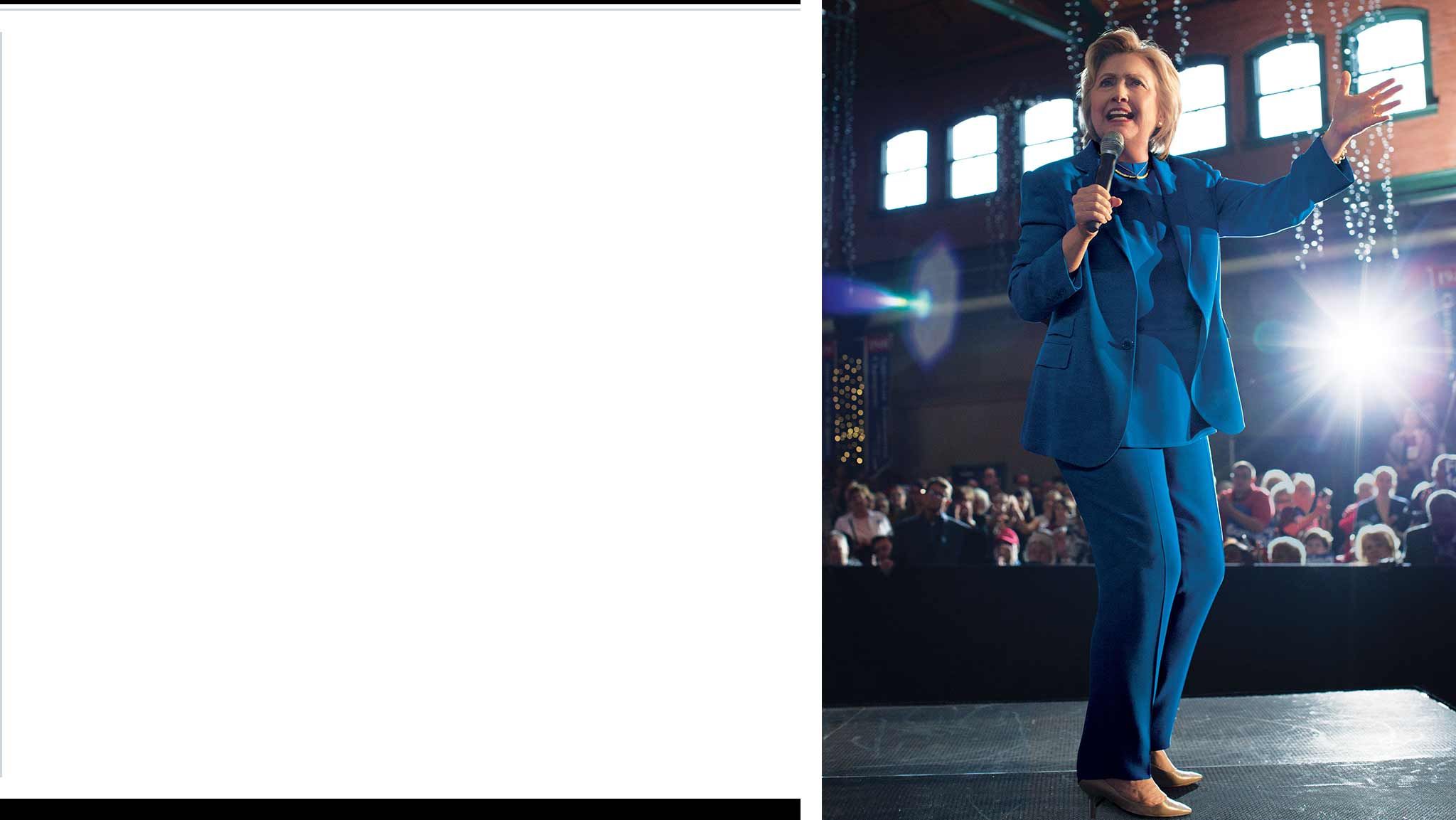

Then, she unwraps a lozenge and puts it in her mouth. She clasps her hands in front of her and looks down at them for a few seconds. Suddenly her head is up and she is striding into the crowd of flashing iPhones and I’M WITH HER signs. She raises her hand and waves at the crowd, grinning. “Hello, Bridgeport!” she bellows.

The idea that, at this point, there is some version of Hillary Clinton that we haven’t seen before feels implausible. Often, it feels like we know too much about her. She has been around for so long — her story, encompassing political intrigue and personal drama, has been recounted so many times — that she can seem a fictional character. To her critics, she is Lady Macbeth, to her adherents, Joan of Arc. As a young Hillary hater, I often compared her to Darth Vader — more machine than woman, her humanity ever more shrouded by Dark Side gadgetry. These days, I think of her as General Leia: No longer a rebel princess, she has made a wry peace with her rakish mate and her controversial hair and is hard at work, mounting a campaign against the fascistic First Order.

All the epic allusions contribute to the difficulty Clinton has long had in coming across as, simply, a human being. She is uneasy with the press and ungainly on the stump. Catching a glimpse of the “real” her often entails spying something out of the corner of your eye, in a moment when she’s not trying to be, or to sell, “Hillary Clinton.” And in the midst of a presidential campaign, those moments are rare. You could see her, briefly, letting out a bawdy laugh in response to a silly question in the 11th hour of the Benghazi hearings, and there she was, revealed as regular in her damned emails, where she made drinking plans with retiring Maryland senator and deranged emailer Barbara Mikulski. Her inner circle claims to see her — to really see her, and really like her — every day. They say she is so different one-on-one, funny and warm and devastatingly smart. It’s hard for people who know her to comprehend why the rest of America can’t see what they do.

I spent several days with Hillary Clinton near the end of primary season — which, in campaign time, feels like a month, so much is packed into every hour — and I began to see why her campaign is so baffled by the disconnect. Far from feeling like I was with an awkward campaigner, I watched her do the work of retail politics — the handshaking and small-talking and remembering of names and details of local sites and issues — like an Olympic athlete. Far from seeing a remote or robotic figure, I observed a woman who had direct, thoughtful, often moving exchanges: with the Wheelers, with home health-care workers and union representatives and young parents. I caught her eyes flash with brief irritation at an MSNBC chyron reading “Bernie Sanders can win” and with maternal annoyance as she chided press aide Nick Merrill for not throwing out his empty water bottle. I saw her break into spontaneous dance with a 2-year-old who had been named after her, Big Hillary stamping her kitten heels and clapping her hands and making “Oooh-ooh-ooh” noises. I heard her proclaim, with unself-conscious joy, from the pulpits of two black churches in Philadelphia, that “this is the day that the Lord has made!” and watched the young campaign staff at her Brooklyn headquarters bounce up and down with the anticipation of getting to shake her hand.

But what the rest of America sees is very different. Clinton’s unfavorability rating recently dipped to meet Trump’s at 57 percent; 60 percent think she doesn’t share their values, 64 percent think she is untrustworthy and dishonest (and that doesn’t even account for the fallout from the inspector general’s report about her private email server). Some of this is simply symptomatic of where we are in the election cycle, near the end of a bruising primary season, with Democratic tempers still hot even as the Republicans are falling in line behind their nominee. But some of it is also unique to Clinton, who has been plagued by the “likability” question since she was First Lady (and, indeed, even before that).

In a recent column, David Brooks posited that Clinton is disliked because she is a workaholic who “presents herself as a résumé and policy brief” and about whose interior life and extracurricular hobbies we know next to nothing. There’s more than a little sexism at work in Brooks’s diagnosis: The ambitious woman who works hard has long been disparaged as insufficiently human. And the Democratic-leaning voters least likely to view Clinton favorably, according to a recent Washington Post poll, skew young, white, and male. But those guys aren’t the only ones she’s having trouble reaching. And, no, it’s not really because we don’t know her hobbies (though if that is a burning question for you, read on).

The dichotomy between her public and private presentation has a lot to do with the fact that she has built such a wall between the two. Her pathological desire for privacy is at the root of the never-ending email saga, to name just one example. But how do you convince a woman whose entire career taught her to be defensive and secretive that the key to her political success might just be to lay all her cards on the table and trust that she’ll be treated fairly? Especially when she might not be.

There are a lot of reasons — internal, external, historical — for the way Clinton deals with the public, and the way we respond to her. But there is something about the candidate that is getting lost in translation. The conviction that I was in the presence of a capable, charming politician who inspires tremendous excitement would fade and in fact clash dramatically with the impressions I’d get as soon as I left her circle: of a campaign imperiled, a message muddled, unfavorables scarily high. To be near her is to feel like the campaign is in steady hands; to be at any distance is to fear for the fate of the republic.

After the rally in Bridgeport, Clinton suggested we return to the locker room where she had met the Wheelers. In the middle of the room there was, improbably, an enormous gray sectional sofa. It did not smell good, but it was comfortable. And Clinton, who had begun this day in Chappaqua and spoken at churches in Philadelphia before flying to Bridgeport, and still had a fund-raiser ahead of her, was tired. She sank into the couch, and reclined. She was, briefly, in repose.

In the rare interviews that Clinton gives, she generally sticks close to her boilerplate talking points, but today she seemed a little looser, perhaps because this was the most relaxed period she’d had in months. It was the weekend between the New York primary and the Pennsylvania, Connecticut, Maryland, Delaware, and Rhode Island contests, of which she would win four of five. Clinton had loved campaigning in New York, a state she knows well and where she is known. She was feeling confident about the next round. And she’d been near enough to her home to return there most nights. “The beauty of the East Coast,” Matt Paul, Clinton’s former Iowa state director who now serves on her communications team, had told me the day before: “She can sleep in her own bed.”

When she’s within even a couple hours’ range of Chappaqua, Clinton tries to spend her nights there, often with her husband. Sometimes they’re coming home from an evening event together, sometimes separately, but the routine is the same. “We get back to the house and stay in the kitchen and talk and maybe eat something bad, maybe drink something bad.” Clinton’s bad drinks include mostly beer and wine, and she considers them bad not for moral but for health reasons. “We watch TV, like the hundreds of shows we record and finally get to.” They like House of Cards, Madam Secretary, The Good Wife (i.e., television shows about them), plus Downton Abbey and NCIS; the football season recently screwed up the couple’s DVR recordings, cutting off the end of Madam Secretary and causing great upset in the Clinton household. “Then [we] go to bed and read for a while before we fall asleep.”

Cynics convinced the pair share only a Faustian bond will surely not believe the vision of domestic compatibility laid out by the former secretary of State. But those who know them attest that their connection is not only authentic but central to both of their mental states. “Think about it,” said one campaign staffer. “If you’re them, how few people you can talk to, really talk to, and have them understand — whether it’s politics or policy or your emotional state.” One associate of Bill’s told me that, especially as he ages, if he goes too long without being in the same place with Hillary, the former president gets grumpy and harder to deal with. Integrating Bill with the campaign has been tricky: There are few people who have more experience — or more opinions — about polling, messaging, and winning the presidency than … the former president. He is a resource, and an eager one, regularly taking on an exhausting surrogate schedule. But there is such a thing as too many presidents in the kitchen; in 2008, Hillary’s overreliance on his team of advisers, including the much-loathed Mark Penn, hobbled her. This time around, Bill phones in to campaign calls and attends some meetings, but, said one campaign source, “not in a way that is so institutionalized as to be debilitating or so scattershot as to be debilitating.”

A good morning for Hillary involves eight hours of sleep (though she often gets no more than four or five), scrambled eggs, and some yoga. “If I get a good balance — tree or whatever — I’m a happy camper,” she says. “If I have a good warrior pose that I’m really holding and looking incredibly strong?” — here she holds out her arms to the side, showing me the top half of Warrior Two — “I’m happy. I’m not good at it and would never pretend that I was, but I find it really restorative and helpful to keep my energy and flexibility going.”

In person, she presents, at 68, as a nana. When she tells me what she reads, she sounds just like my mother and so many other women I know, describing how she has become addicted to mystery novels. She cites the Maisie Dobbs books by Jacqueline Winspear and Donna Leon’s series set in Venice, explaining, “I’ve read so much over the course of my life that now I’m much more into easier things to read. I like a lot of women authors, novels about women, mysteries where a woman is the protagonist … It’s relaxing.”

Of course Clinton is no cinnamon-scented Mrs. Tiggy-Winkle; the grandmothers of today are the generation of women who were the first to get advanced degrees in huge numbers, and to march, first down Fifth Avenue, and then, shoulder-padded and bespectacled, into workplaces. In 1947, the year Clinton was born, there were no women serving in the Senate. Clinton remembers, as a girl, running home from her suburban Chicago primary school on Fridays to read Life magazine, which is where she discovered Margaret Chase Smith, the first woman elected to both houses of Congress, and was “just amazed that this woman did this.”

By the time Clinton graduated from Yale Law School, many people, including her boyfriend Bill, believed she could, and should, embark on a political career. She’d given the Wellesley commencement speech that had earned her a Life write-up of her own. She had volunteered for New Haven’s legal-services clinic, worked on Walter Mondale’s subcommittee investigating the living and working conditions of migrant laborers, spent a year accompanying doctors on rounds at Yale New Haven Hospital researching child abuse, and begun work for her future mentor and boss, Marian Wright Edelman. In 1973, she would publish a well-regarded paper on children’s legal rights, and in 1974, she worked for the committee to impeach Richard Nixon. There were few young people, men or women, with that kind of résumé.

Bill Clinton famously had to propose to Hillary Rodham several times before she agreed to marry him and move to Arkansas. In recent years, he’s started telling a version of the story in which he was urging her not to marry him, and instead run for office in New York or Chicago, and in which she replied that that was a ridiculous idea: She was too aggressive; no one would vote for her.

“I don’t think he said that when he actually proposed,” she told me with a smile when I brought up this version of the story. “But it was kind of a theme that he would go back to.” He wasn’t the only one. The conviction of many of her friends that she should go into politics stemmed, she said, from the fact that “I was really interested in politics and I was really interested in policy and there weren’t that many young women who were. So the fact that I was kind of catalyzed people’s imagining … ‘Oh my gosh, you could run for office!’ ” But, Clinton said, in those days she saw herself as “an advocate, using my legal training, using whatever other skills I had to investigate, research, speak out.” In other words, Clinton pictured herself, as generations of other ambitious women had, as being of service, not as a headliner.

Political possibilities for women were expanding, slowly. Margaret Chase Smith had run for president in 1964, Shirley Chisholm in 1972. In 1984, Walter Mondale named Geraldine Ferraro as his running mate. “That was a big moment for me,” said Clinton. “I was at the convention because Bill was governor. And it was so thrilling.” She took Chelsea to meet Ferraro when she came through Little Rock to campaign.

But Clinton didn’t begin to take her own political prospects seriously until she was approached in 1998 by New York officials about running for Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s Senate seat. The timing was complicated. Moynihan had announced his retirement just a month before Bill Clinton’s impeachment vote. “We were coming out of two terms in the White House,” Clinton told me. “I really [didn’t] know that that’s what I want[ed] to get right into.” Clinton loves telling the story of what finally convinced her: At an event for women athletes called “Dare to Compete,” a teenage basketball captain, Sofia Totti, said to her, “Dare to compete, Mrs. Clinton, dare to compete.” The exhortation gave her pause. “It was like, ‘Am I just scared to do this? Is that really what it comes down to?’ ”

She had good reason to be scared. By 1999, even without having pursued her own political path, Clinton had learned what it might entail to be a woman who competed: She had taken her husband’s last name after his 1980 reelection defeat in Arkansas had been blamed on her independence; she’d done cookie-bake-off penance for her remarks about prioritizing career over domesticity; everything from her friend Vince Foster’s death to the wandering attentions of her husband had been tied to her purported ruthlessness.

When I asked her why she thinks women’s ambition is regarded as dangerous, she posited that it was about “a fear that ambition will crowd out everything else — relationships, marriage, children, family, homemaking, all the other parts [of life] that are important to me and important to most women I know.” She also mentioned the unappealing stereotyping: “We’re so accustomed to think of women’s ambition being made manifest in ways that we don’t approve of, or that we find off-putting.”

She also edged toward something uglier, harder to talk about. “I think it’s the competition,” she said. “Like, if you do this, there won’t be room for some of us, and that’s not fair.” I pushed her: Did she mean men’s fears that ambitious women would take up space that used to belong exclusively to them? “One hundred percent,” she said, nodding forcefully.

She told a story about the time she and a friend from Wellesley sat for the LSAT at Harvard. “We were in this huge, cavernous room,” she said. “And hundreds of people were taking this test, and there weren’t many women there. This friend and I were waiting for the test to begin, and the young men around us were like, ‘What do you think [you’re] doing? How dare you take a spot from one of us?’ It was just a relentless harangue.” Clinton and her friend were stunned. They’d spent four safe years at a women’s college, where these kinds of gender dynamics didn’t apply.

“I remember one young man said, ‘If you get into law school and I don’t, and I have to go to Vietnam and get killed, it’s your fault.’ ”

“So yeah,” Clinton continued. “That level of visceral … fear, anxiety, insecurity plays a role” in how America regards ambitious women.

The sexism is less virulent now than it was in 2008, she said, but still she encounters people on rope lines who tell her, “ ‘I really admire you, I really like you, I just don’t know if I can vote for a woman to be president.’ I mean, they come to my events and then they say that to me.”

But, she maintains, “Unpacking this, understanding it, is for writers like you. I’m just trying to cope with it. Deal with it. Live through it.”

Here, Clinton laughed, as if living through it were a hilarious punch line.

There’s a video of Clinton on YouTube from 2007 that some on her campaign staff watch when they need a laugh, a classic “That’s so Hillary” moment. In the clip, she’s concluding a campaign event when a bunch of American flags fall over, a full-on equipment malfunction. As Clinton helps to right the flags, she cannot keep herself from offering some flag-related tips to the relevant officials: “I think that the bases are not weighted enough; that’s your problem.”

Clinton is a master at identifying problems and coming up with plans to solve them. There is seemingly no crisis too small to escape her attention, no subject outside her wheelhouse. When she turns her energies onto bigger issues, her ability to see an interlocking set of concerns and her detailed knowledge about … everything can sound like a parody of female hypercompetence.

When Clinton rolled out a progressive set of policies for families at her May events in Lexington and Louisville, her explanation went something like this: We need a national system of paid family leave because too many women don’t even get a paid day off to give birth; workers don’t have a federal requirement for paid sick days; meanwhile, many dads and parents of adopted children don’t get any time off at all, and sons and daughters don’t get time to take care of aging parents. We also need to establish voluntary home-visiting programs, where new parents, especially those facing economic adversity, can get assistance in learning how to care for their children and prepare them to succeed in school, thus taking aim at unequal outcomes in the earliest years. Relatedly, we need to raise wages, because two-thirds of minimum-wage workers are women, which has an impact on single-parent and dual-earning homes and, when combined with high child-care costs, inhibits women’s ability to earn equal benefits, save for college, and put away for retirement. Minimum-wage workers currently spend between 20 and 40 percent of their income on child care; Clinton has a plan whereby no family would pay more than 10 percent on child care, but she also believes we need to increase pay for child-care providers and early educators, who in some places are paid less than dog trainers and who have their own families to take care of. All of this is tied to the need to strengthen unions and make health care more affordable through revisions to the Affordable Care Act as well.

Clinton’s holistic view of intersecting challenges and multi-tentacled solutions — tax incentives, subsidies, wage hikes, pay protections — is weirdly thrilling in its expansive perspicacity. But it does not fit on a T-shirt. It does not sound good at a rally. You cannot even really show it on the local news, because it is not as simple as, say, “Free college!”

Or, as Joe Scarborough put it recently, “You want to go to sleep tonight? Go to Hillary Clinton’s website and start reading policy positions.”

It’s not uncommon for women to be tagged as dull pragmatists in this way. The history of politics and of progressive movements, after all, is one of women doing the drudge work and men giving the inspiring speeches. It wasn’t Dorothy Height or Rosa Parks or Pauli Murray or Diane Nash or Anna Hedgeman — hardworking activists and lawyers and organizers — who gave the big speeches on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. Before she finally decided to run for office, Shirley Chisholm once said, she had “compiled voter lists, carried petitions, rung doorbells, manned the telephone, stuffed envelopes, and helped get voters to the polls. I had done it all to help other people get elected. The other people who got elected were men, of course, because that was the way it was in politics.”

Clinton self-identifies as a worker more than as a speechmaker. When I told her during one of our conversations that the comedian Samantha Bee had described her to me as “a working dog; you’ve got to give Hillary a job,” her eyes lit up. “When I got to the Senate, I said I was not a show horse!” she reminded me. It seems the thing Clinton is proudest of in the world.

You can hear her barely disguised scorn for show horses when she tells me about her “admiration” for her Democratic rival Bernie Sanders. “His passion and his intensity and his consistent message have been really resonating with a proportion of the electorate,” she said. “You can go so far with the top lines. And, you know, I get it. I mean, I admit that some people are really much better at that than I am.” But she cannot help following up with: “When you really get into it and people are thinking, ‘Who’s going to be my president? Who cares about my kids’ education? Who’s really going to fix the Affordable Care Act so it’s more affordable?’ You have got to be prepared. And I feel that this campaign will be more than prepared.”

But being prepared is a Girl Scout motto, not a campaign slogan. Hard work is, perhaps oddly, not all that inspiring a trait in presidential candidates. For inspiration, we still demand the rhetorical high notes. Clinton has hit them before, in her speech in Beijing as First Lady, when she said, “Women’s rights are human rights,” and in her 2008 concession speech, when she talked about the “18 million cracks” in the glass ceiling. But those were both instances when she embraced her own symbolic significance as a woman — something she has long been hesitant about.

Years ago, her former speechwriter Lissa Muscatine told me of an argument they often had back when Clinton was First Lady: “I used to tell her, ‘You’re not using the symbolic power of your position,’ ” to which Clinton would reply, “That’s not going to effect systemic change or make a lasting impact.” Muscatine’s counterargument was that “sometimes you effect the change through the symbolic act.”

I asked Clinton if it still makes her uncomfortable to be thought of as a symbol. “No,” she replied. “I’ve really kind of matured in my understanding of how symbolism can be efficacious, so I’m more embracing of that. But at the end of the day, being the first woman president can only take you so far. What have I done that can actually produce positive results in somebody’s life? Do we have more jobs? Are people’s incomes going up? Have we made progress on the minimum wage? What have we gotten done on equal pay? What are we doing on early childhood?” She is right back in worker mode. “I’m still a results-oriented kind of person, because that’s what I think matters to people.”

Of course, it’s not just her ambivalence about how to handle her historic firstness that’s at the root of Clinton’s problems as a campaigner. It’s also a pervasive defensiveness that gets in the way of her projecting authenticity, an intense desire for privacy that keeps voters from feeling as if they know her — especially problematic in an era in which social media makes personal connection with voters more important than ever. Clinton’s wariness about letting the world in is in part her personality and in part born of experience. A lifetime spent in the searing spotlight has taught her that exposure too often equals evisceration. It’s worth remembering that Clinton’s public identity was shaped during the feminist backlash of the ’80s and early ’90s, when saying that you didn’t want to bake cookies was enough to start a culture war.

If Clinton suffers from a kind of political PTSD that makes her overly cautious and scripted and closed-off, then its primary trigger is the press corps that trails her everywhere she goes. Clinton hates the press. A band of young reporters follows her, thanklessly, from event to event, and she gives them almost nothing. Unlike other candidates, she does not ride on the same plane with them (though this may change once the general election starts and the traveling group gets bigger). Every once in a while she has an off-the-record drink with them, but without the frequency or fluidity of her husband, whose off-the-record conversations with the press were legendarily candid.

These young reporters are so starved for what they call “fresh sound” that they thrill to the addition of a new line — about Trump being “a loose cannon” — or even a word (“Basta!”) to Clinton’s stump speech. They want to know Clinton better, and are occasionally so eager to get a fuller picture of their subject that, in conversation with each other, they turn to fan fiction. On the night that Beyoncé’s Lemonade video aired on HBO, the traveling press, unable to livestream it on the bus through Philadelphia, was keeping track via Twitter and imagining that somewhere, on their plane back to New York, Huma was filling in Hillary on Becky with the Good Hair. Some were joking about Clinton’s earlier mispronunciation of Queen Bey’s name (she had emphasized the wrong syllable), performing a kind of Maya Rudolph skit in which the candidate was saying, “Huma, what is happening with my good friend Bay-ONS-uh?” They debated which one of them would ask her the next day about Lemonade, but no one did, mostly because none of them got close enough to her.

Most of the traveling reporters are too young to remember the way Clinton was barbecued by the media from the beginning, labeled too radical, too feminist, too independent, too influential; dangerous, conniving, ugly and unfuckable. But it’s clear that even today she and her campaign feel that they can’t win with the press, that the story lines about her are already written. Case in point: In early May, the New York Times ran a feature about Clinton’s wooing of Republicans turned off by Donald Trump, which sent supporters of Bernie Sanders into a frenzy of I-told-you-so’s about Clinton’s crypto-Republicanism. The paper barely acknowledged that days later Clinton teed up her plan for subsidized child care and raising the wages of caregivers — proposals that would have been understood not long ago as something out of a ’70s feminist fever dream. There was also little media notice of her declaration, that same week, that she would remove bankers from the boards of regional Federal Reserve banks — an announcement that should have pleased left-leaning champions of financial reform.

Of course, some of the media’s reluctance to acknowledge Clinton’s very progressive domestic-policy agenda as “very progressive” is because of the campaign’s hesitancy to frame it that way. Maybe she’s still skittish, years later, about being called a left-wing feminazi. Or maybe it’s because she lacks the gifts her husband and Barack Obama have for doing what politicians do: pandering to opposing factions while appearing sincere to both. Clinton is a terrible actor and an awkward speaker, prone to badly phrased pronouncements that muddy, or even seem to reverse, her message. So far this year, her stump speeches have relied on weird infrastructural metaphors about tearing down barriers and building ladders of opportunity. (Her usually smooth-talking husband recently took it to the next level, suggesting that Clinton wants to “build an escalator to the future we can all ride on.”)

One of the biggest recent flubs from the Not Great Communicator was in Kentucky, when Clinton harkened back, as she often does with certain crowds, to the good old days of her husband’s administration. But this time she suggested, carelessly, that she was going to put Bill “in charge of revitalizing the economy, because you know he knows how to do it.” Social media — and traditional media — went nuts; the Times ran a full story on it, suggesting that Clinton’s “passing promise” indicated that “Mr. Clinton would be put in charge of a significant part of a president’s portfolio.”

It was a (bad!) rhetorical error in which she gracelessly crossed the (bright!) line between invoking Bill’s name and naming him to a post. That she hadn’t intended it was made clear by the manner in which she practically rolled her eyes when saying “No” to a follow-up question about whether she’d appoint her husband to her Cabinet. But this is the price Clinton pays for not having a warmer, closer relationship with reporters: She does not get the benefit of any doubt; there is no elasticity of comprehension. She does not enjoy the goodwill that someone like Joe Biden — a king of misstatements, prone to offending entire nationalities — has earned, which permits him to get out of media-jail time and again.

“There is no doubt that she has to walk a narrower path than some other politicians,” a frustrated Nick Merrill told me on the day of the Bill Clinton comments. Merrill, her press aide, was irritated by the willingness of the media to blow the remark into a fantasy scenario, at their refusal to believe the campaign’s clarification that no, there was no “official” role secretly being planned for the former president should his wife be elected. “When she says something — not even off-script, but gives a stump speech and talks about her husband and uses fewer words or less-exact words than she did the week before — it’s hard to put that toothpaste back in the tube. There’s an assumption that there’s some underlying secret.”

And this is the rub exactly: Everyone assumes Clinton is harboring an underlying secret. It’s a paranoiac cycle — Clinton and her team think that everyone is after her, and their behavior creates further incentive for everyone to come after her. But at some point, cause and effect cease to matter. Defensiveness, secrecy, and a bunkered combativeness (that perhaps relates to her worrying hawkishness) are her very real shortcomings. The question is whether they can be overcome by her very real strengths, especially as she prepares to take on a man whose own flaws are so outsize.

There is an Indiana Jones–style, “It had to be snakes” inevitability about the fact that Donald Trump is Clinton’s Republican rival. Of course Hillary Clinton is going to have to run against a man who seems both to embody and have attracted the support of everything male, white, and angry about the ascension of women and black people in America. Trump is the antithesis of Clinton’s pragmatism, her careful nature, her capacious understanding of American civic and government institutions and how to maneuver within them. Of course a woman who wants to land in the Oval Office is going to have to get past an aggressive reality-TV star who has literally talked about his penis in a debate.

For all the hand-wringing about how she will hold up against a bully who has already made it clear he will attack her in the most shameless ways imaginable, Clinton seems extremely pleased about the prospect of running against him. “I’m actually looking forward to it,” she told me. “See, I don’t think it’s as fraught with complexity as some people are suggesting. I think the trap is not to get drawn in on his terms. We saw what happened to those Republicans who tried.”

Clinton says she knows what he’ll say about her — her marriage, her husband. She says she doesn’t care; she can ignore it. “But that doesn’t mean you don’t stand up for everybody else he’s insulting,” she said. “That doesn’t mean you don’t talk about where his policies would take this country, to draw the contrast.”

“If she’s looking forward to Trump, it’s because she’s dealt with some really unsavory characters and behind-the-scenes diplomatic maneuvering,” said Muscatine. “And I think she’s really effing good at it. Benghazi is like the zenith, where the whole point was just to eviscerate her and by the end she’s kind of flicking dust off her collar. I think she knows this about herself; not that she’s at all arrogant about it, just that she knows how to do it. She kind of relishes the gamesmanship.”

Clinton is better when she is forced off the script, something the unpredictable Trump is likely to do. In a recent interview with Anderson Cooper on CNN, Cooper asked Clinton about the fact that her opponent will make hay of her husband’s infidelities. She laughed, “Well, he’s not the first one, Anderson!” and it was a good line, a human line. It was a meta-example of something that could happen in debates.

The next phase of the campaign will be, at the very least, clearer. We have not yet experienced Hillary Clinton as a general-election candidate, permitted to fight without one hand tied behind her back. We’ve only seen her in tough primaries, her natural base of support divided in its loyalties, pitted against beloved men with good politics — men she could not hit too hard, lest her negative words ever be used against them and their losses laid at her feet.

Even now she is careful around Sanders. She has long ceased going after him in her speeches and will say to me only that she thinks “that interview he gave to the New York Daily News was incredibly damaging … because you’ve got to get to the second, third, fourth, fifth levels of analysis and understanding.”

But Sanders has managed to land significant blows, not least about her high-priced speeches for Wall Street firms during the gap years between her time at State and her second presidential campaign. Sources close to her make the defensive case: that nothing about those speeches compromised her positions, that she had the right to make money in the private sector during her brief hiatus from public service. But in an era when there is ongoing fury about the stark chasm between the wealthy and everyone else in this country, there is no persuasive explanation for her decision to take the money for those speeches, or why she won’t release the transcripts — other than her deeply ingrained belief that hunkering down is the only way to weather these storms.

Sanders has had the effect of making Clinton appear more, not less, defensive, and she has suffered for it. Still, the campaign is taking the long view, assuming that her unfavorables will drop back down when the primaries are over, which they expect to be soon, regardless of what happens in California. Clinton feels protected by the delegate math, even though delegate math, as one person close to the campaign says, is not a vision.

So you can see why she would be anxious to get out of the primary morass and do direct battle with Trump. “When you get to a two-person race, it’s not you against the almighty and perfection that is hoped for,” says Clinton. “It’s you against somebody else.”

She’s confident enough about her prospects against Trump that she is thinking beyond the general to what could happen after Inauguration Day. “One of the reasons I’m hoping we can secure the nomination,” she says, “is that I really don’t just want to pivot politically into a campaign, I want to pivot into preparation. Because there’s so much that needs to be prepared” — here she ticks off comprehensive immigration reform, equal pay, and paid family leave, which some in her campaign have hinted could be her first priority. But Clinton says she wants to abandon old thinking about strategy; she wants to challenge the notion that a president has to pick which issue to move on first, assuming an initial two-year window of congressional possibility.

“I want to take everything I’ve said I’m going to work on and be as teed up as possible from the very beginning. I want to give [Congress] every opportunity to move forward on several fronts.” Of course, that plan is somewhat dependent on whether Democrats can take back the Senate, in which case, she says, “I’ve got Chuck Schumer as my partner. And he’s a great legislative strategist and I think we can really try to figure out how to push on several fronts.”

Some on her team hope that, recognizing the nation’s appetite for upheaval, Clinton will go for broke with her vice-presidential pick, staying away from the safe choice of Tim Kaine or someone like him, and instead make the mother of all I-am-woman-hear-me-roar moves by picking Massachusetts senator Elizabeth Warren. It would be a risky, and therefore out-of-character, move for Clinton. But even without a ticketed alliance, the communication between the Clinton and Warren camps has been steadily increasing, according to sources with knowledge of the relationship. On May 24, the Clinton campaign launched its first coordinated attack against Trump, releasing a video showing the Republican reveling in having profited from the subprime mortgage crisis. That evening, Warren echoed the campaign’s talking points in a speech at the Center for Popular Democracy gala, calling Trump “a small, insecure, money-grubber who doesn’t care who gets hurt.”

Whether she chooses Warren or not, this is an election that may require Clinton to take some uncharacteristic risks. What the nomination of Trump, the enthusiasm for Bernie Sanders, and the nomination of Clinton — who is very clearly running as a successor to Barack Obama — tell us is that this election is a kind of civil war. It’s a referendum on the country’s feelings about inclusion, about women, people of color, and their increasing influence, and how it edges out the white men who have long had an exclusive grip on power.

This would have been less clear if Clinton had been running against Marco Rubio, or against Jeb Bush, men who would have hidden the Republicans’ backward-looking policies — around voting rights, reproductive rights, opposition to minimum-wage increases — behind rhetoric about empowered women and diversity. Trump does away with any pretext. He calls women pieces of ass and rates them on scales of one to ten; he encourages violence, fails to firmly disavow David Duke, promises walls to keep out immigrants and to ban Muslims from entering the country.

Ironically, this could give Clinton the thing she has had such a hard time mustering on her own: righteous symbolism. She doesn’t have to talk about herself, she just needs to be herself, in order to make the point that she represents inclusion, equality, progress. In Trump, she finds her foil: America’s repressive past.

On the night of the West Virginia primary, which her campaign knew she would lose to Sanders, Clinton arrived at Louisville Slugger Field in advance of a rally that was scheduled there. It’s rare for Clinton to arrive early anywhere, and she was enjoying a moment to herself in one of the stadium’s luxury boxes, looking out over the beautiful, empty minor-league baseball field, smiling.

“I really love baseball,” she said, seemingly to herself.

We chatted for a while about Mother’s Day — she spent it with granddaughter Charlotte — and about the fact that Chelsea and Marc Mezvinsky aren’t going to find out the sex of their new baby until its birth this summer. She talked grimly about the health center we had just visited, and about the Republican governor’s efforts to dismantle Kentucky’s health-care exchange, one of the most successful in the nation. She mused about how sad it is that voters’ anger toward Obama in 2012 left them here, four years later, about to lose the health-care benefits he fought for.

I asked her whether the time she was spending in Kentucky, a red state, reflected more than her desire to win the primary there the following week (which she did, by a hair). Her eyes lit up; it’s as if she’d been waiting for someone to ask her about the surprising possibilities of the electoral map this year. So which states do you think Trump puts in play? I asked, mentioning the possibility of Georgia, which some think could go Democratic for the first time since her husband won it in 1992.

“Texas!” she exclaimed, eyes wide, as if daring me to question this, which I did. “You are not going to win Texas,” I said. She smiled, undaunted. “If black and Latino voters come out and vote, we could win Texas,” she told me firmly, practically licking her lips.

An hour later, Clinton was giving her stump speech at a rally inside the Louisville Slugger Hall of Fame. Outside it was pouring on the ball field; inside there were twinkling lights. Polls would soon close in West Virginia, giving Bernie Sanders more momentum. But in front of this ecstatic crowd, Clinton sounded jubilant. “They’re going to throw everything including the kitchen sink” at me, she told the crowd. “But I have a message for them: They’ve done it for 25 years, and I’m still standing!” The crowd howled its approval. “I am looking forward to debating Donald Trump in the fall,” she hollered, several decibels more loudly than she needed to, into the mike. “Do we have disagreements? Yes,” she said. “That’s healthy! There are lots of different ways to achieve our goals … But you don’t do that by denigrating people, demeaning people. That is not who we are. And it is time we said, ‘Enough!’ ”

Watching her, I wondered if it’s possible, after all these years, once she has slipped the bonds of constrained primary combat, that she could emerge as a better and freer performer. In some ways, it seems necessary — not just to win but to govern. After all, the presidency is a public, performative job. She can’t just suffer through the indignity of campaigning and then hole up with her policy papers. It’s not enough to have a plan; you have to sell it to the country, over and over again. Obama proved to be particularly adept at using the media to disseminate his administration’s messages to the audiences it was trying to reach, but he is a masterful orator. Bill Clinton, too. Even George W. Bush was charismatic in his way.

But if, as in this election, a man who spews hate and vulgarity, with no comprehension of how government works, can become presidentially plausible because he is magnetic while a capable, workaholic woman who knows policy inside and out struggles because she is not magnetic, perhaps we should reevaluate magnetism’s importance. It’s worth asking to what degree charisma, as we have defined it, is a masculine trait. Can a woman appeal to the country in the same way we are used to men doing it? Though those on both the right and the left moan about “woman cards,” it would be impossible, and dishonest, to not recognize gender as a central, defining, complicated, and often invisible force in this election. It is one of the factors that shaped Hillary Clinton, and it is one of the factors that shapes how we respond to her. Whatever your feelings about Clinton herself, this election raises important questions about how we define leadership in this country, how we feel about women who try to claim it, flawed though they may be.

Can we broaden our idea of presidential charisma beyond great men giving great speeches? Ed Rendell, former governor of Pennsylvania, made the case to me that Clinton should try to design the job — as much as she can, anyway — around her. “The president gets to select the mode of communicating,” he said. “The president can go out and make speeches in front of large audiences, or the president can make the speech sitting behind the desk talking to a TV camera. The president can do sit-down interviews. If I were Hillary’s chief of staff, I’d get her on as many of those interview shows as I could and just get her talking and not reading a speech. I’d have her do town meetings all through her presidency. Have you seen her in small town halls? Hillary is not a great large-crowd speaker, but in those contexts, I would rate her as close to spectacular.”

I thought back to the roundtable discussion I had seen in Lexington, where Clinton was meeting with dozens of parents whose kids had been enrolled at the day-care center where she was speaking. A single mother named Jessica McClung, who struggled to earn her undergraduate degree while raising her son, had been so nervous upon meeting Clinton backstage, before the discussion started, that she had become tongue-tied. She couldn’t speak, so Clinton took over. “Don’t be nervous,” she told McClung, regarding her with the same steady look I’d seen her train on the Wheelers. “Don’t be nervous. Just talk to me, look at me, take a deep breath, forget about all this” — here Clinton gestured at the cameras and Secret Service, the cumbersome machinery that trails her everywhere, and which she herself has such a hard time forgetting about. “Just talk to me.”

*This article appears in the May 30, 2016 issue of New York Magazine.