Hillary Clinton has spent much of the past two months arguing that Ronald Reagan would not vote for Donald Trump. At the Democratic National Convention, a series of speakers — including Barack Obama — argued that the patron saint of the conservative movement would recoil at Trump’s authoritarian ethos. At a recent press conference, the Democratic nominee suggested that the Gipper would be incensed to see the Republican nominee praise Vladimir Putin while disparaging the American president. A new ad from her super pac, released this week, casts Reagan’s ghost as a Clinton surrogate.

The point of all this nostalgia for the man who killed off the New Deal consensus was to isolate the Republican nominee from his party’s upscale wing. In polls, Trump consistently underperforms past GOP standard-bearers with college-educated whites. The Clinton campaign sought to capitalize on suburban Republicans’ apparent alienation from their populist nominee, by focusing on the many nonideological reasons why Trump shouldn’t be president (i.e., the fact that he’s a racist, misogynist, authoritarian with a taste for conspiracy theories and no experience in government). This was also the strategic logic behind Clinton’s “alt-right” speech, in which she cast Trump as the champion of a reactionary online movement that defines itself in opposition to the Republican mainstream. By the end of that address, Clinton had contrasted the hatefulness of Trump’s meme-savvy minions with the principled tolerance of such statesman as Bob Dole, George W. Bush, John McCain, and House Speaker Paul Ryan.

This focus on winning over socially moderate, fiscally selfish suburbanites generated some grumbling among progressives. But their complaints centered on the possibility that the message would undermine Democrats down-ballot — not that it would undermine Clinton herself.

Trump’s resurgence in recent polls calls the latter point into question. While many analysts have tied the tightening race to Clinton’s health and “email” woes, there are signs that the candidate’s broader strategy has also played a role.

For one thing, that strategy doesn’t appear to be accomplishing its ostensible goal: Clinton boasts the support of a whopping 6 percent of self-identified Republicans in the latest Reuters/Ipsos poll — while Trump lays claim to 8 percent of self-identified Democrats.

At the same time, Clinton has failed to consolidate the support of the Democratic base. Recent polls show more than 30 percent of (largely liberal) millennials defecting to third-party candidates, while nonwhite voters are backing Clinton at lower levels than they did Obama. And the Democrats who have rallied behind Clinton are less enthusiastic about her candidacy than they were two months ago.

There are many potential explanations for these findings. It’s possible that headlines about foundation donors and walking pneumonia have blunted the efficacy of Clinton’s appeals to light Red America.

But it’s also possible that, by focusing on Trump’s lack of “fitness” — and the ugly idiosyncrasies that separate him from other Republicans — Clinton has allowed Trump to escape the unpopularity of his party’s economic agenda.

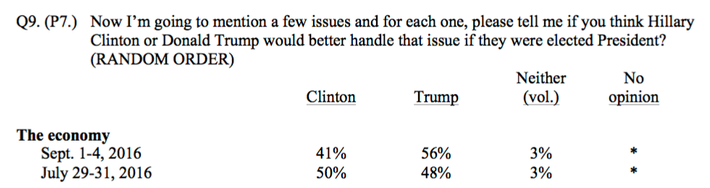

Immediately after the Democratic Convention, a CNN/ORC survey put Clinton ahead of Trump by eight points. Earlier this month, that same poll put Trump ahead of her by two. That swing inspired no small amount of panic in progressives’ social-media feeds. But an even more dramatic change can be found beneath the headline figures:

Clinton went from winning the economic debate by two points, to losing it by 15. Considering the fact that “the economy” is the electorate’s number-one concern, this seems like a shift worth dwelling on.

While Clinton has put forward a robust economic agenda, much of her messaging has directed attention away from it: You can’t make a full-throated case for a progressive economic vision and insist that this election is about “more” than left versus right. The second argument inevitably crowds out the first. How much moral urgency can you put into your case for expanding social welfare, while still casting Paul Ryan — a man who has worked tirelessly to cut nutritional benefits to needy children — as a kind of honorable public servant? Forced to choose between conveying a clear ideological message and courting the broadest possible coalition against Trump, Clinton opted for the latter.

This made some sense when Clinton was leading by 10 points, and looking to engineer a landslide. It makes less sense today. Especially since the center-left’s agenda is, on paper, way more popular than Trumponomics.

More than 60 percent of Americans believe the rich should pay higher taxes. Same for raising the federal minimum wage. And while polling data is limited, evidence strongly suggests that expanding Social Security is a big winner for Democrats. At the very least, tying Trump to his party’s affinity for Social Security cuts couldn’t hurt: More than two-thirds of Republicans don’t want to see benefits reduced. Similarly, there is little appetite among voters of either party for deregulating the finance industry. And yet, the GOP nominee has committed himself to doing just that.

Throughout his campaign, Trump has deliberately branded himself as a Republican unconstrained by fealty to conservative dogma. At various points, he’s feigned openness to raising taxes on the super-rich and increasing the minimum wage, explaining, “I’m very different from most Republicans.”

But, on most areas of economic policy, he truly isn’t. And by encouraging the public to see Trump as something other than a Republican, Clinton may have lent credibility to his own claim of independence from Paul Ryan’s losing agenda.

While Trump has struck heterodox stances on trade, infrastructure spending, and subsidized child care, he has embraced supply-side economics, Wall Street deregulation, leaving the federal minimum wage right where it is, and, most recently, the abolition of food-safety standards. What’s more, he has reportedly signaled an openness to entitlement cuts behind closed doors.

It’s not hard to craft a message that connects these unpopular policies to Trump’s character liabilities. Clinton and her surrogates have done it many times; they just haven’t centered their campaign around the charge: “Donald Trump is a con artist who is trying to hoodwink working people into voting for the one-percent’s agenda.”

To be sure, there’s no guarantee that this message will prove effective. But shifting the debate to the realm of economic policy should at least help re-energize the Democratic base — calls for expanding Social Security are more likely to generate liberal enthusiasm than paeans to the moral courage of George W. Bush.

And who knows, maybe a populist economic message could flip a Trump-leaning non-college educated white voter or two. While Trump’s appeal among that demographic is largely racial and cultural, there’s still evidence that economic concerns are a factor. Lost amid the (warranted) celebration of the rosy economic data released this week, is the fact that, outside metro areas, wages actually declined in 2015.

Regardless, the Clinton campaign recognizes that it can’t keep doing what it has been. On Wednesday in North Carolina, Clinton put less emphasis on Trump’s outrages than she did on her own virtues as a conscientious technocrat. But her attack lines were still premised on Trump’s personal failings, not the GOP’s ideological ones.

Distancing Trump from the Party of Reagan hasn’t worked. Tying him to that party’s plutocratic agenda might.