The decision of when and if to work with Donald Trump could force Democrats to choose between their political self-interest and their policy goals. It is easy to imagine instances where cooperation would be worth the price: If they can pry him away from his intent to destroy the international climate-change agreement, or to throw 20 million Americans off their insurance, it would be worth elevating his standing.

But Jennifer Steinhauer’s report describes a completely different kind of thinking among the party’s Senate leaders. They apparently believe that cooperating with Trump will provide them with a political advantage, and are seeking out potential issues — infrastructure, child care, trade — to do so. This is a disastrous misreading of all the evidence of how politics works.

The belief that helping Trump might elevate their own standing has a certain surface-level appeal. Trump won white voters in swing states that Democrats need. The most important reason for his success was intense, widespread distrust of Hillary Clinton, but to the extent the election carries lessons going forward other than “have a less-hated nominee than Hillary Clinton,” embracing economic populism is a sensible one. Their mistake is the apparent belief by many Democrats that they can burnish their reputation for economic populism by joining with Trump. The Times presents the party as facing a political choice: “Make common cause where they can with Mr. Trump to try to win back the white, working-class voters he took from them, or resist at every turn, trying to rally their disparate coalition in hopes that discontent with an ineffectual new president will benefit them in 2018.”

This would be a sensible way to conceive of the choice if voters judged the congressional party independently of how it judged the president. But a vast array of political-science research finds just the opposite. The single accountability mechanism through which the public makes its political choices is the president. If the president is seen as succeeding, voters will reward his party. If he is seen as failing, they will punish it. Presidential approval is so dominant it even drives voting in state legislative races. What’s more, scholars have found, cooperation from Congress sends a signal that the president is succeeding, and conflict sends a signal of failure.

This was the strategy Republicans embraced from the outset of the Obama administration. “We’ve got to challenge them on every bill and challenge them on every single campaign,” said Representative Kevin McCarthy at a meeting before Obama’s inauguration. The Republican Congress understood that bipartisan cooperation of any kind would elevate Obama and lead voters to reward his party for it.

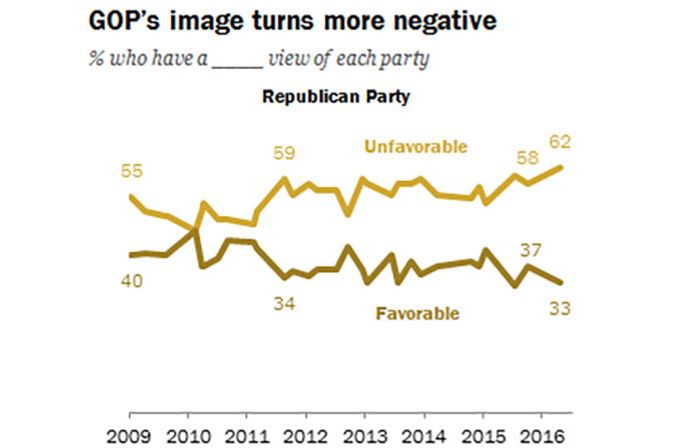

It’s notable that the Republican Party faced an extremely serious reputational problem in 2009. It had overseen a disastrous presidency culminating in an economic calamity, and was seen as incompetent, economically elitist, and socially regressive. But the most important thing to understand is that the Republicans never solved this problem at all. Indeed, the problem, to the extent it is a problem at all, has actually gotten worse. America hates the Republican Party more now than it did when Obama took office:

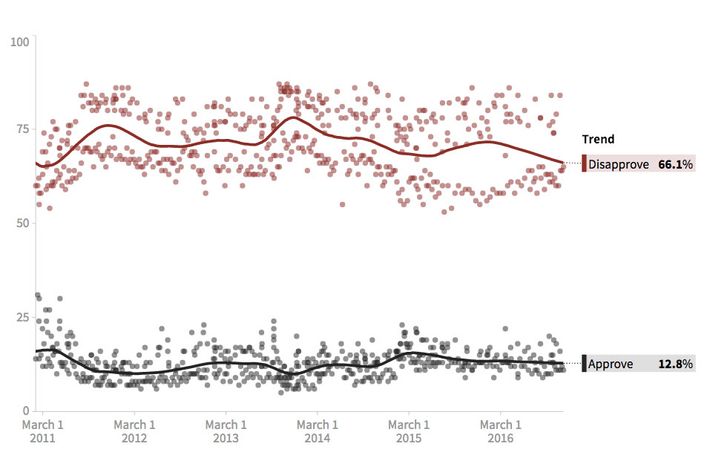

When Republicans took control of Congress in 2010, some Democrats hopefully believed that they would at least share some accountability for the state of the country. But the Republican Congress has been wildly unpopular throughout the entire period of its control:

Has this prompted the public to decide to give Democrats a shot at running Congress? No, it has not. The entire last eight years have been a Republican social-science experiment dedicated to proving that they can be as partisan, crazy, dangerous, and racist as they want without adverse political effect. What this tells Democrats is that working with Trump is the surest way to help him win reelection and his party to maintain its control of Congress.

But what about the economic-populism problem? Here the answer is very easy. They can attack Trump and his party as corrupt handmaidens of the rich and powerful. This is a simple, intuitive theme that has the additional benefit of being completely true. Clinton’s campaign focus on Trump’s unfitness for office had the side effect of allowing him to position himself as an outsider, albeit perhaps a dangerous one, who would blow up the system.

In reality, his administration is a bonanza for economic elites. The Democratic Party should be repeating every word of this Ben White story in Politico, which reports, “Wall Street bankers and their Washington lobbyists are quietly celebrating.” Trump’s administration is stuffed with Wall Street bankers, and it is poised to shower them with tax breaks and lax regulation. What’s more, Trump himself is engaging in unprecedented levels of corruption by intermingling his public office and the continuation of his business. He and his family are almost certainly going to enrich themselves through power, and their nondisclosure policy will mean the public will have no accountability. The only actual accountability mechanism for this dangerous kleptocracy is an opposition party that hammers every Trump decision as potential self-dealing. The correct infrastructure strategy, for instance, is to define an opposing pro-infrastructure plan while lambasting Trump’s as a crooked giveaway that will make his rich business pals richer without much of anything to repair infrastructure. This attack line appeals to intuitive cynicism about politicians, and also happens to be accurate.

Winning on economic populism means blowing up Trump’s reputation as the friend of the little guy. To accommodate his claim to help the working class, by legitimizing his plans for infrastructure or child care, is to surrender. Again, there may be vital substantive or humanitarian cases where the Democrats should sacrifice their political interest in order to cooperate with Trump. But the idea that cooperating will help their party is simply wrong.