Last week, Richard Hanna, a Republican from central New York who just retired from Congress, admitted something that almost no member of his party in elected office has been willing to concede in public. “At the end of the day, the Affordable Care Act will in some form survive, and the millions of people who are on it will have insurance,” he said. “It’s something this country needed and something people want. Politically, it’s untenable to just wipe it away. So who really won? In my argument, the president, Obama, won. At the end of the day we will have some sort of national health care that’s going to look very similar to what we have.” The mania for destroying the law is faltering because the Republican crusade to kill Obamacare was always based on delusions that are no longer possible to conceal.

In the aftermath of the presidential election that handed them full control of government, Republicans quickly converged on a plan to execute their longtime battle cry of repealing Obamacare: They would immediately repeal the law, perhaps even signing the bill to do it on Inauguration Day, after which they would have leverage over shattered Democrats to force the opposition party to supply votes to pass whatever the majority came up with. Since that point, they have moved steadily backward.

In early January, several Senate Republicans indicated opposition to repealing Obamacare without a replacement — enough defections to kill repeal, given that the party can only lose two Senate votes. The plan to quickly repeal, and then figure out a replacement, appears to have been halted, and the party has yet to decide what will take its place. A week after the inauguration, a secret recording of a Republican Congressional brainstorming session revealed the party had not advanced beyond step one in conceptualizing a plan, let alone achieving consensus on any of the numerous dilemmas they would need to resolve. “We’re in the information-gathering mode right now,” says Representative Mark Meadows. At the current trajectory, sometime next week, a Republican staffer will Google “What is health care?”

In an interview Sunday with Bill O’Reilly, President Trump conceded that health care was “very complicated,” and floated a timetable for devising a replacement that could extend into next year:

Yes, in the process and maybe it’ll take till sometime into next year, but we’re certainly going to be in the process. Very complicated — Obamacare is a disaster. You have to remember Obamacare doesn’t work, so we are putting in a wonderful plan. It statutorily takes a while to get. We’re going to be putting it in fairly soon. I think that, yes, I would like to say by the end of the year, at least the rudiments, but we should have something within the year and the following year.

While Trump is known to be an unreliable narrator of his own administration’s policy, the climbdown from his characteristic boasting of rapid victory is nonetheless striking. He seems to have absorbed from his advisers the difficulty of the situation and the need to reel back expectations.

As the Republicans continue their long retreat, they are encountering every false premise that brought them to this point. The most important of these is a misconception about Obamacare’s popularity. For most of the time since 2010, polls have showed negative approval for the law, the single fact that conservatives have leaned on most heavily since 2010. Of the countless polemics against the Affordable Care Act that have appeared since 2010, the law’s mediocre approval ratings are the data points conservatives invoke more than any other. It is the foundation for their belief the law is corrupt and was passed illegitimately, that the public shares the GOP’s root-and-branch rejection of its very design, and that Republicans have a mandate to repeal it.

Supporters of the law have had a different explanation for its poor approval ratings. People have very little information about what the law does, and even many people who benefit from it are not aware. The long, tortured negotiations required to pass the law did not prove the process was corrupt or failed, but that health-care reform is intrinsically difficult. People will fight much harder to avoid losing a benefit they have — even if that benefit is not actually at risk — than to create a new one they don’t. Proponents of health-care reform always believed that bringing health care into reality would make it much easier to defend.

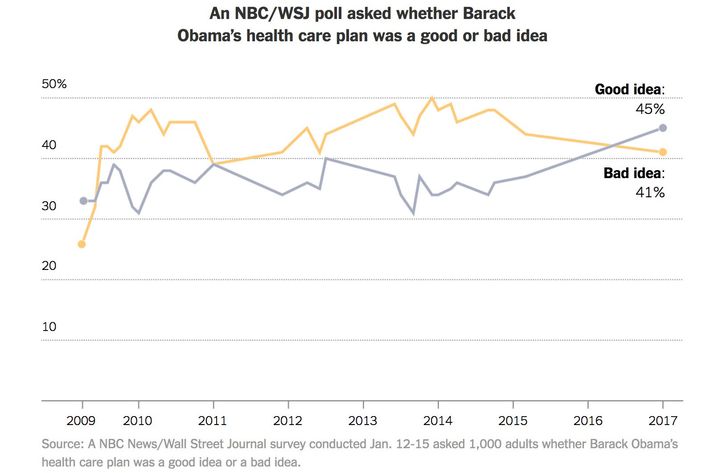

That has turned out to be correct. The law’s growing popularity can be seen across several dimensions. Repealing Obamacare first, without a replacement, is wildly unpopular, drawing 20 percent approval or less. Repealing the law and starting over with a new one — the Republican position since 2010 — draws support from one-third of the public, while keeping Obamacare and fixing it gets nearly twice as much support. On the straightforward question of whether Barack Obama’s health-care reform was a good idea or a bad one, for the first time ever, “good idea” now wins:

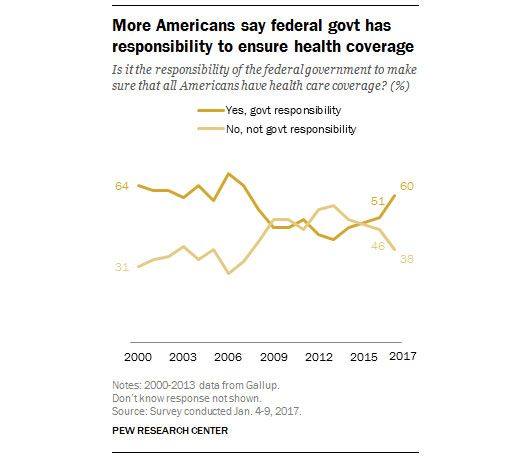

And Americans by a significant margin believe it is the government’s responsibility to make sure everybody has coverage:

The chart above is especially telling. Notice that a huge majority agreed that the government should cover everybody before and after Obama’s presidency, but that support collapsed during the time of an administration attempting to implement this goal. Political scientists have long recognized that public opinion has a thermostatic element, demanding more government services during Republican presidencies, and less during Democratic ones. It is striking how fast public opinion has swung — this is even before Republicans have begun to publicly debate an alternative plan, which would contain all sorts of unpopular specific elements that would drive down its support even farther.

Republicans suffer from an additional handicap that Democrats did not face in 2010: they are not merely over-promising what they can deliver, they are promising the exact opposite. While GOP rhetoric has lambasted the cost of plans offered by Obamacare, their alternatives would all impose even higher costs. An extended public debate over actual, filled-out Republican plans that force people onto catastrophic plans that do not cover basic medical expenses would be a political debacle.

It is not only majority opinion that is swinging against Republicans on health care. Lobbyists, too, tend to organize against change. Hospitals are demanding that Republicans either keep covering the Americans who have insurance through Obamacare, or else compensate the hospitals for the losses they would suffer from facing millions of customers who can longer pay for their care. AARP has staked out opposition to one of the GOP’s favorite proposals to tweak Obamacare, which would allow insurers to charge even higher rates to older customers. Obamacare only permits insurers to charge older customers up to three times as much as the young. Republicans have railed against the burden this places on younger workers buying insurance — and it’s true that Obamacare makes the young pay more so the old can pay less. But now Republicans are learning the difference between posturing against a law, and cherry-picking its downsides, and actually having to endorse an alternative position. When you have to pick winners and losers, not just complain about the losers in the other party’s law, you make people mad.

The energy among political activists has reversed, too. In 2009, tea-party activists flooded town halls and harried Democrats, often frantic with terror at imaginary “death panels” they believed the law would contain. Now it is advocates of Obamacare mobilizing in anger and chasing terrified Republican members of Congress down the street. Conservatives spent years lionizing demonstrations against Obamacare as the justifiable anger of a free people. Now they can see what health-care reform looks like from the opposing end.

There is no guarantee that Obamacare will survive. The Republican majority may decide melting down the health-care markets is worth the backlash. It wouldn’t be the first time they have taken a political gamble that seemed irrational. It’s possible that the Trump administration might intend to preserve Obamacare but wind up killing it through sheer managerial incompetence; a White House that can screw up something like an introductory phone call with the prime minister of Australia could screw up anything.

Still, the pattern of the three months since the election shows the cause of Obamacare repeal collapsing. Obama and his party were able to design a plan that squared the minimal humanitarian needs of the public with the demands of the medical industry. There is no evidence at all that Trump and his party can do the same. It is dawning on the Republicans that the cost of destroying this achievement in social policy may well be to destroy their majority.