With Ajit Pai and the FCC rolling back rules protecting an open internet, allowing your internet-service provider to stop acting as a public common carrier, there’s been speculation about what exactly will happen. One common talking point is that this is just a return to normalcy, and customers don’t need to worry about the results.

Here’s Doug Brake, senior telecommunications policy analyst at the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (which gets a fair amount of funding from telecom companies), writing today in an op-ed for The Hill:

[Pro-net neutrality] agitators want to preserve common-carrier classification under Title II for one and only one reason: They want the Internet to be a highly regulated utility. They aren’t interested in a productive conversation about an innovation-oriented internet and communications system. Weeks before Pai’s proposal was to be released, some were already labeling it a “catastrophe.” But the reality is that Pai looks to be returning broadband to the legal regime that seemed to have worked pretty well from the dawn of the commercial Internet up until 2015.

This is, frankly, horseshit. While it may have appeared to the average consumer that the internet before the FCC regulation “worked pretty well,” the back end was an unseemly mess that actively made using the internet worse. To briefly explain: Between your end connection and the internet at large lies your ISP, which provides that final “last-mile” delivery of services. Your ISP taps into the internet at physical ports, known as internet-exchange points.

As the rise of streaming HD video took off at the turn of the decade, led mainly by Netflix, ISPs realized that they were about to get hosed. Consumers were going to start needing a lot more bandwidth, and ISPs would have to invest capital to provide it, including upgrading and adding many more internet-exchange points.

But thanks to a lawsuit by New York’s attorney general Eric Schneiderman against Time Warner Cable about slow broadband speeds, we have internal emails and graphs from Time Warner Cable (now known as Spectrum after a merger with Charter Communications last year) that show how at least one ISP allegedly saw its soon-to-be-overwhelmed infrastructure not as a problem, but as a source of potential profit.

One Time Warner Cable exec wrote in 2011 that the company’s strategy, when it came to upgrading its physical internet-exchange points, should be focused not on providing the best service, but on getting content providers like Netflix to pay for the right to get a direct connection to paying subscribers. If the content provider didn’t pay up, it would be forced “through transit,” meaning its data would go through a slower, more circuitous route to your television or laptop screen. “We really want content networks paying us for access,” wrote the unnamed exec, “and right now we force those through transit that do not want to pay.”

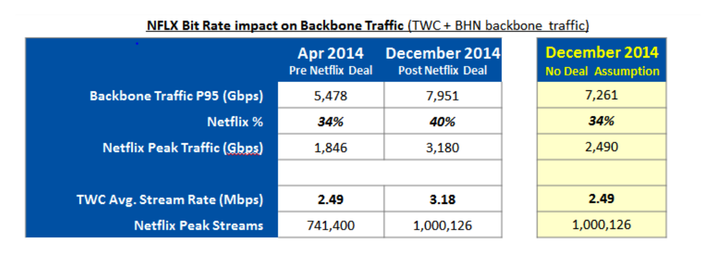

This meant Time Warner Cable and Netflix entered into a series of extended negotiations. Until Netflix agreed to pay, Time Warner Cable refused to add more internet exchange points between Netflix and its customers, resulting in broadband speeds dipped below what Netflix needed to deliver HD streaming. This meant Time Warner Cable customers often experienced buffering and degradation of video quality while watching Netflix. Netflix finally agreed to pay up in late 2014, and an internal graph produced by Time Warner Cable shows how the payoff worked to speed up Netflix, and how slow things would have remained if Netflix hadn’t coughed up the cash (it’s the second-to-last row you want to focus on):

Time Warner Cable, during its long and contentious negotiations with Netflix, never told customers that their Netflix connections were slower because Netflix wasn’t paying up — in fact, at the same time Time Warner Cable was deliberately neglecting the infrastructure needed to support Netflix, its ads explained why Time Warner Cable could deliver Netflix without buffering.

This wasn’t just happening at Time Warner Cable — Netflix eventually signed the same type of deal with every major ISP. It’s only because of the lawsuit in New York against Time Warner Cable that we know the internal thinking of one ISP — but it’s a safe assumption that the same calculations were being made at every other major ISP as well. Netflix needed to be able to directly connect to an ISP’s network, therefore Netflix had to pay up. And Netflix wasn’t the only company that had to enter into these deals. Time Warner Cable did the same thing to companies like Riot Games, which makes the extremely popular online game League of Legends, and “backbone” internet providers that actually deliver the vast majority of what you see online.

Anti-net-neutrality proponents may argue that this was simply a problem of transparency — the only problem was that Time Warner Cable customers didn’t know their Netflix speeds sucked because of behind-the-scenes negotiations — but otherwise, Time Warner Cable should be able to strike whatever deals it wants with content providers. But entrenched monopolies mean that even in some alternate reality — where Time Warner Cable, instead of bragging about its Netflix speeds, ran TV ads and put up billboards all across New York openly announcing that it was deliberately providing slower streaming speeds in order to extract money from a company — it wouldn’t have mattered.

Time Warner Cable (Spectrum) was (and still is) by far the largest internet provider in New York State, and in some cities, like Rochester, it’s the only one. The same is true across the country — per the FCC itself, about 48 percent of Americans live somewhere where only one ISP offers internet speeds faster than 25 Mbps, and one in five can only choose one ISP for any broadband access at all. Either the content provider pays up or the service remains slow, and the customer remains caught in the middle.

It’s likely that your Netflix streaming speed won’t be affected by this rollback — CEO Reed Hastings has publicly said he’s not worried because Netflix is “too popular” for ISPs to try to alter direct-connection deals. But smaller content providers (including would-be competitors to Netflix) don’t have that luxury, and new tech will inevitably come down the line that will place new demands on broadband speeds. When that happens, unregulated ISPs will engage in the same anti-consumer practices that they did before. We don’t have to imagine how it will happen, because we’ve seen it before.