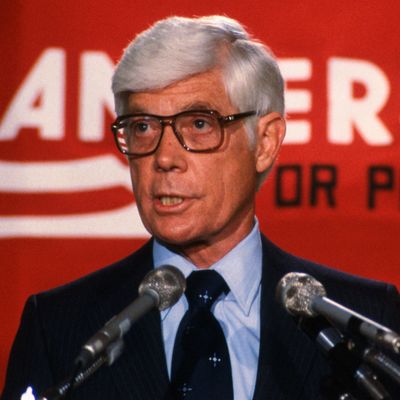

John B. Anderson of Illinois, who died today at the age of 95, served in Congress for 20 years. But what gave him national fame was a briefly sensational independent candidacy for president in 1980, running against President Jimmy Carter and soon-to-be-president Ronald Reagan. By doing so, Anderson represented two milestones in modern political history: He was the most conspicuous of early conscientious objectors to the conservative movement’s takeover of the Republican Party, and he was the prototype for the kind of centrist third-party presidential candidate that so many pundits and billionaires long for in today’s era of partisan polarization.

Anderson was not, of course, the first moderate-to-liberal Republican to oppose the rightward drift of his party. But he was the first to take an unsuccessful presidential primary candidacy right out of the GOP and into an independent ballot line. He took that fateful step in part because of the low regard he had for Ronald Reagan, his vanquisher in the primaries. But he also realized his brand of socially liberal, fiscally conservative politics had a stronger constituency outside his own party.

And that made him the classic “centrist” third-party candidate for president (his only rival in the last century was Ross Perot, whose unorthodox positions really disqualified him from the “centrist” label unless it was modified by “radical”).

For a while, Anderson’s campaign was quite the phenomenon. In June his National Unity Party ticket (with running mate Pat Lucey, a Democratic former governor of Wisconsin) was polling at 24 percent according to Gallup. But as is typically the case, voters returned to the two major parties as the election approached. And in fact, Anderson largely abandoned his centrist positioning in order to poach liberals from Jimmy Carter, whose Evangelical background, fiscal conservatism, and cool relationship with Israel alienated a lot of usually Democratic voters. I recall seeing Anderson speak in San Francisco in the fall of 1980, by which time he was emphasizing his progressive social views, including what was then an unusual attitude of support for gay rights.

In the end, Anderson won only 7 percent of the vote, and his National Unity Party vanished without a trace. By 1984, Anderson was endorsing Democratic presidential nominee Walter Mondale. And so he was the prototype for millions of other relatively liberal Republicans who trended Democratic as even larger numbers of conservative Democrats joined the GOP. He had a distinguished later career as chairman of the electoral-reform group FairVote, which promotes a national popular vote and ranked-choice voting.

Anderson was never afraid to take heretical positions. His signature economic proposal in 1980 was a 50-cent-per-gallon federal gasoline tax increase with the proceeds to be devoted to a cut in the Social Security payroll tax. It’s still a pretty good idea, if not necessarily something that would poll well, much like Anderson himself.