The GOP understands how important labor unions are to the Democratic Party. The Democratic Party, historically, has not. If you want a two-sentence explanation for why the Midwest is turning red (and thus, why Donald Trump is president), you could do worse than that.

With its financial contributions and grassroots organizing, the labor movement helped give Democrats full control of the federal government three times in the last four decades. And all three of those times — under Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton, and Barack Obama — Democrats failed to pass labor law reforms that would to bolster the union cause. In hindsight, it’s clear that the Democratic Party didn’t merely betray organized labor with these failures, but also, itself.

Between 1978 and 2017, the union membership rate in the United States fell by more than half — from 26 to 10.7 percent. Some of this decline probably couldn’t have been averted — or, at least, not by changes in labor law alone. The combination of resurgent economies in Europe and Japan, the United States’ decidedly non-protectionist trade policies, and technological advances in shipping was bound to do a number on American unions. Global competition thinned profit margins for U.S. firms; cutting labor costs was one of the easiest ways to fatten ’em back up; and breaking unions (through persuasion, intimidation, or relocation) was one of the easiest ways to cut said costs.

Nevertheless, there was lot that Democrats could have done — through labor law reform — to shelter the union movement from these changes, and help it establish a bigger footprint in the service sector. At present, employers are prohibited from firing workers for organizing or threatening to close businesses if workers unionize — but the penalties for such violations are negligible. Further, while they must recognize unions once they are ratified by workers in an election, employers can delay those elections for months or even years — and, even after recognition, face no obligation to reach a contract with their newly unionized workers.

Democrats could have increased the penalties for violating labor law, enabled unions to circumvent the election process if a majority of workers signed union cards (a.k.a. “card check”), and required employers to enter arbitration with unions if no contract was reached within 120 days of their formation — as Barack Obama promised the labor movement they would, in 2008.

Or, if they were feeling a bit more radical, they could have repealed the part of the Taft-Hartley Act that allows conservatives states to pass “right to work” laws. Such laws undermine organized labor by allowing workers who join a unionized workplace to enjoy the benefits of a collective bargaining agreement without paying dues to the union that negotiated it. This encourages other workers to skirt their dues, which can then drain a union of the funds it needs to survive.

And that has the effect of draining the Democratic Party of the funds — and grassroots organizing — that it needs to thrive. As Sean McElwee writes for The Nation:

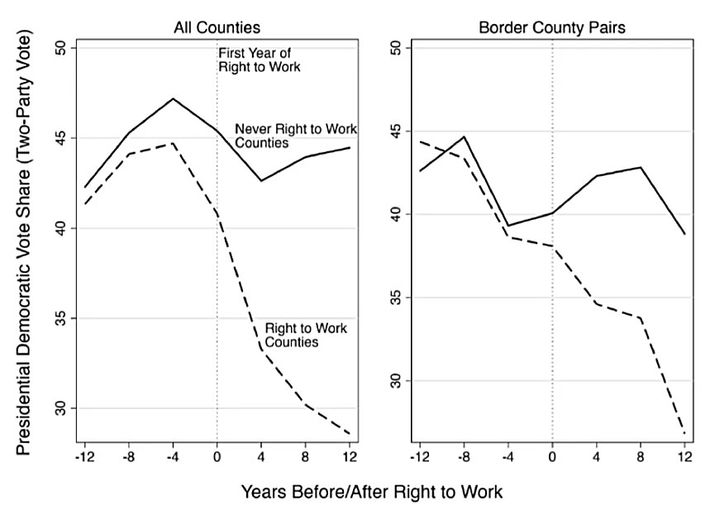

In a new study that will soon be released as a National Bureau of Economic Research working paper, James Feigenbaum of Boston University, Alexander Hertel-Fernandez of Columbia, and Vanessa Williamson of the Brookings Institution examined the long-term political consequences of anti-union legislation by comparing counties straddling a state line where one state is right-to-work and another is not. Their findings should strike terror into the hearts of Democratic Party strategists: Right-to-work laws decreased Democratic presidential vote share by 3.5 percent.

The study found that impacts persist in down-ballot races, and have given Republicans more power in the Senate, House, and governors’ mansions, as well as in state legislatures. This leads to a vicious cycle wherein the GOP can use that power to further suppress votes, gut union rights, and gerrymander legislatures—in other words, embark on a fundamental retooling of American political mechanics.

The decimation of the blue wall in 2016 may have been driven by Trump’s unique candidacy, but right-to-work laws had been weakening the foundation for years. In 2014, Republican Governor Rick Snyder’s narrow victory against Democratic opponent Mark Schauer may well have gone in a different direction were it not for the state’s 2012 right-to-work law. It’s not impossible to imagine that progressive Senate candidate Russ Feingold would have beaten Tea Party–backed incumbent Ron Johnson in 2016 if only Wisconsin private- and public-sector unions had not been completely gutted. The effect of right-to-work laws, according to this research, are large enough that it could have easily cost Hillary Clinton Wisconsin and Michigan—two states that went right-to-work before the 2016 elections.

These findings will surprise no one in the Republican leadership. Since 2010, six GOP state governments have passed “right to work” laws. Last year, Kentucky and Missouri joined the club (the latter development will make Senator Claire McCaskill’s already difficult reelection bid all the more challenging). Republicans prioritized these regressive labor law reforms because they understood how devastating they would be for the unions — and thus, to the Democratic Party. Last year, anti-tax crusader Grover Norquist argued that if right-to-work reforms are “enacted in a dozen more states, the modern Democratic Party will cease to be a competitive power in American politics.”

This could have been a golden age for American liberalism. The Democratic Party — and the progressive forces within it — have so much going for them. The GOP’s economic vision has never been less popular with ordinary Americans, or more irrelevant to their material needs. The U.S. electorate is becoming less white, less racist, and less conservative with each passing year. Social conservatism has never had less appeal for American voters than it does today. The garish spectacle of the Trump-era Republican Party is turning the American suburbs — once a core part of the GOP coalition — purple and blue.

If the Democratic Party wasn’t bleeding support from white working-class voters in its old labor strongholds, it would dominate our national politics. Understandably, Democratic partisans often blame their powerlessness on such voters — and the regressive racial views that led them out of Team Blue’s tent. But as unions have declined across the Midwest, Democrats haven’t just been losing white, working-class voters to revanchist Republicans — they’ve also been losing them to quiet evenings at home. The NBER study cited by McElwee found that right-to-work laws reduce voter turnout in presidential elections by 2 to 3 percent.

Further, the notion that grassroots organizing cannot make a non-woke white man prioritize his class interests over his racial resentments — and thus, that the Democratic Party’s refusal to bolster union organizing was irrelevant to its failure to fend off Trump — is unsupportable. In 2008, labor invested a quarter-billion dollars into Barack Obama’s election, allocating the bulk of those funds into burnishing the candidate’s support among union voters in the Midwest. That year, unionized white men backed Obama by an 18 percent margin; while nonunionized ones went for John McCain by 16.

If right-to-work laws alone cost Democrats roughly 3.5 percent of a given state’s vote share, how many votes has the party lost since 1978 by refusing to prioritize progressive labor reforms?

What kind of country would we live in today, if they hadn’t?