On the same fall night in 2016 that the infamous Access Hollywood tape featuring Donald Trump bragging about sexual assault was made public by the Washington Post and dominated the news, an Alaska attorney, Moira Smith, wrote on Facebook about her own experiences as a victim of sexual misconduct in 1999.

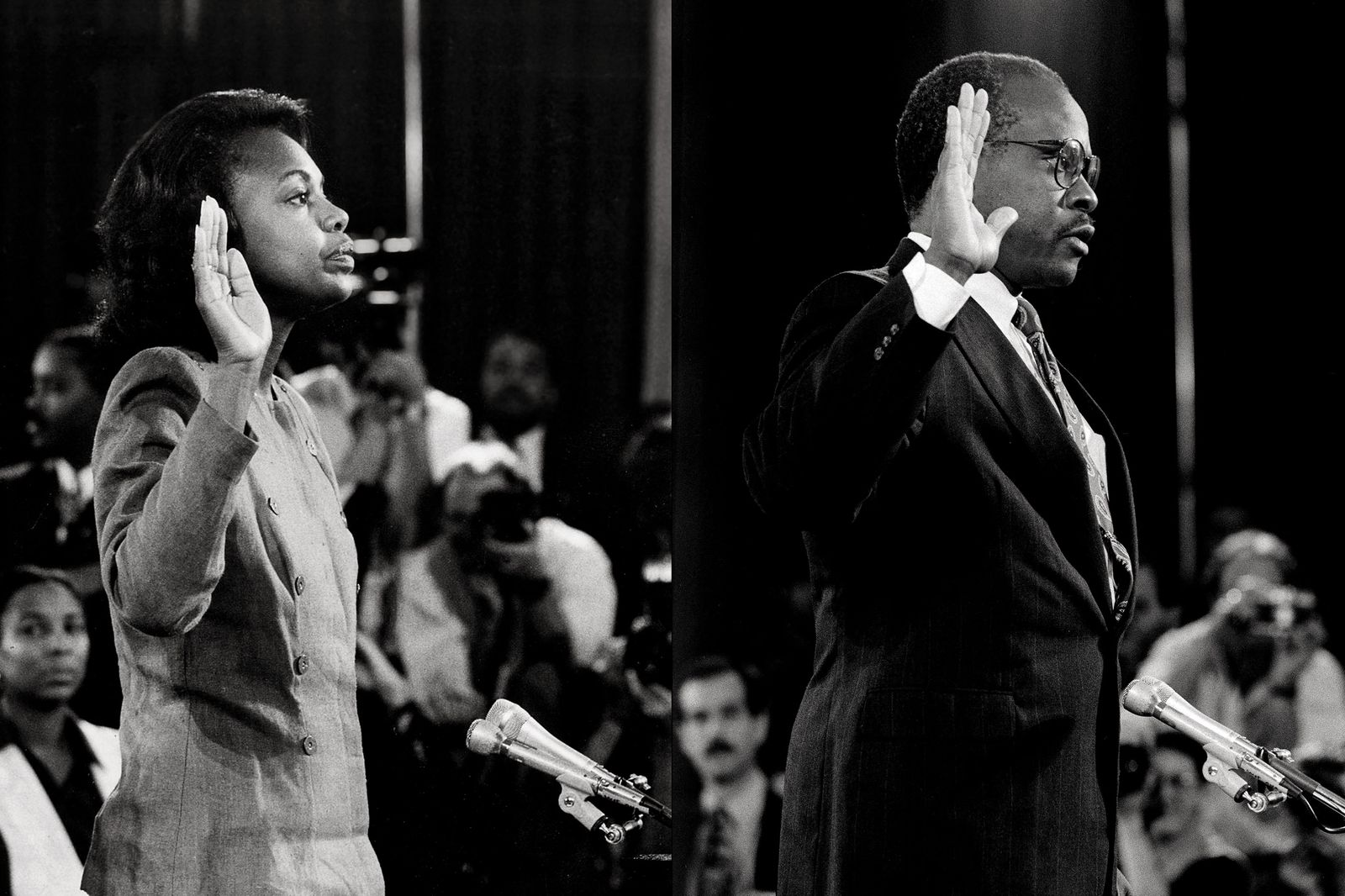

“At the age of 24, I found out I’d be attending a dinner at my boss’s house with Justice Clarence Thomas,” she began her post, referring to the U.S. Supreme Court justice who was famously accused of sexually harassing Anita Hill, a woman who had worked for him at two federal agencies, including the EEOC, the federal sexual-harassment watchdog.

“I was so incredibly excited to meet him, rough confirmation hearings notwithstanding,” Smith continued. “He was charming in many ways — giant, booming laugh, charismatic, approachable. But to my complete shock, he groped me while I was setting the table, suggesting I should ‘sit right next to him.’ When I feebly explained I’d been assigned to the other table, he groped again … ‘Are you sure?’ I said I was and proceeded to keep my distance.” Smith had been silent for 17 years but, infuriated by the “Grab ’em by the pussy” utterings of a presidential candidate, could keep quiet no more.

Tipped to the post by a Maryland legal source who knew Smith, Marcia Coyle, a highly regarded and scrupulously nonideological Supreme Court reporter for The National Law Journal, wrote a detailed story about Smith’s allegation of butt-squeezing, which included corroboration from Smith’s roommates at the time of the dinner and from her former husband. Coyle’s story, which Thomas denied, was published October 27, 2016. If you missed it, that’s because this news was immediately buried by a much bigger story — the James Comey letter reopening the Hillary Clinton email probe.

Smith, who has since resumed her life as a lawyer and isn’t doing any further interviews about Thomas, was on the early edge of #MeToo. Too early, perhaps: In the crescendo of recent sexual-harassment revelations, Thomas’s name has been surprisingly muted.

Perhaps that is a reflection of the conservative movement’s reluctance, going back decades, to inspect the rot in its power structure, even as its pundits and leaders have faced allegations of sexual misconduct. (Liberals of the present era — possibly in contrast to those of, say, the Bill Clinton era — have been much more ready to cast out from power alleged offenders, like Al Franken.)

But that relative quiet about Justice Thomas was striking to me. After all, the Hill-Thomas conflagration was the first moment in American history when we collectively, truly grappled with sexual harassment. For my generation, it was the equivalent of the Hiss-Chambers case, a divisive national argument about whom to believe in a pitched political and ideological battle, this one with an overlay of sex and race. The situation has seemed un-reopenable, having been tried at the highest level and shut down with the narrow 1991 Senate vote to confirm Thomas, after hearings that focused largely on Hill.

But it’s well worth inspecting, in part as a case study, in how women’s voices were silenced at the time by both Republicans and Democrats and as an illustration of what’s changed — and hasn’t — in the past 27 years (or even the last year). After all, it’s difficult to imagine Democrats, not to mention the media, being so tentative about such claims against a nominated justice today. It’s also worth looking closely at, because, as Smith’s account and my reporting since indicates, Thomas’s inappropriate behavior — talking about porn in the office, commenting on the bodies of the women he worked with — was more wide-ranging than was apparent during the sensational Senate hearings, with their strange Coke-can details.

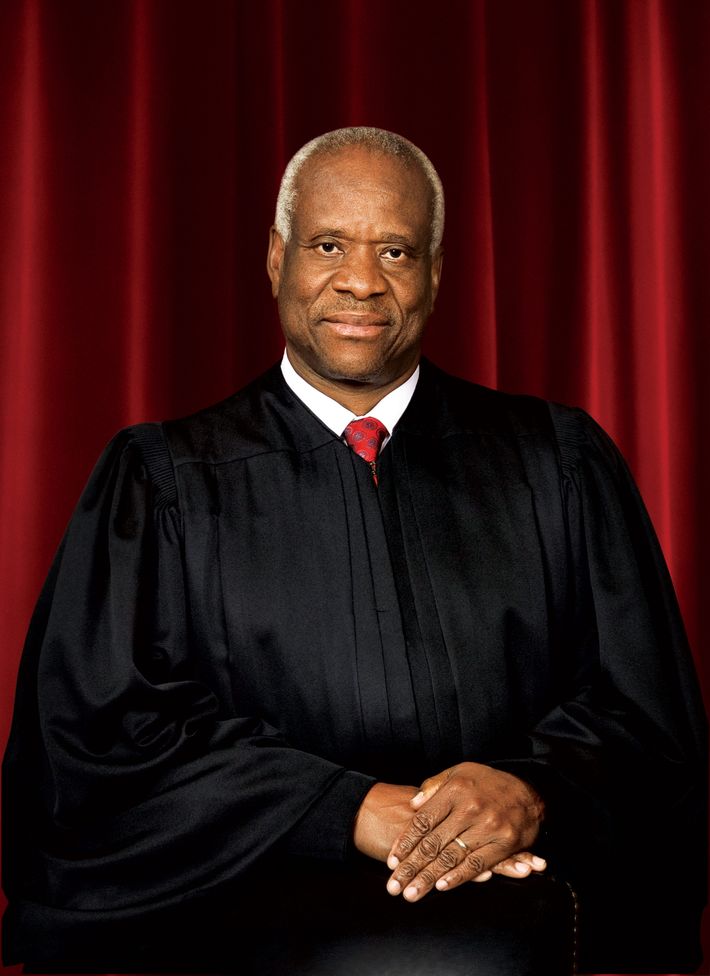

But, most of all, because Thomas, as a crucial vote on the Supreme Court, holds incredible power over women’s rights, workplace, reproductive, and otherwise. His worldview, with its consistent objectification of women, is the one that’s shaping the contours of what’s possible for women in America today, more than that of just about any man alive, save for his fellow justices.

And given the evidence that’s come out in the years since, it’s also time to raise the possibility of impeachment. Not because he watched porn on his own time, of course. Not because he talked about it with a female colleague — although our understanding of the real workplace harm that kind of sexual harassment does to women has evolved dramatically in the years since, thanks in no small part to those very hearings. Nor is it even because he routinely violated the norms of good workplace behavior, in a way that seemed especially at odds with the elevated office he was seeking. It’s because of the lies he told, repeatedly and under oath, saying he had never talked to Hill about porn or to other women who worked with him about risqué subject matter.

Lying is, for lawyers, a cardinal sin. State disciplinary committees regularly institute proceedings against lawyers for knowingly lying in court, with punishments that can include disbarment. Since 1989, three federal judges have been impeached and forced from office for charges that include lying. The idea of someone so flagrantly telling untruths to ascend to the highest legal position in the U.S. remains shocking, in addition to its being illegal. (Thomas, through a spokesperson, declined to comment on a detailed list of queries.)

Thomas’s lies not only undermined Hill but also isolated her. It was her word versus his — when it could have been her word, plus several other women’s, which would have made for a different media narrative and a different calculation for senators. As the present moment has taught us, women who come forward alongside other women are more likely to be believed (unfair as that might be). There were four women who wanted to testify, or would have if subpoenaed, to corroborate aspects of Hill’s story. My new reporting shows that there is at least one more who didn’t come forward. Their “Me Too” voices were silenced.

My history with the Thomas case is a long one. In the early 1990s, along with my then-colleague at The Wall Street Journal Jane Mayer, I spent almost three years re-reporting every aspect of the Hill-Thomas imbroglio for a book on the subject, Strange Justice: The Selling of Clarence Thomas. Quickly, we uncovered a pattern: Clarence Thomas had, in fact, a clear habit of watching and talking about pornography, which, while not improper on its face, was at the heart of Hill’s allegations of sexual harassment. She testified that at the Department of Education and the EEOC, where she worked for Thomas, he had persisted in unwelcome sex talk at work. Often, he’d called her into his office to listen to him describe scenes from porn films featuring Long Dong Silver and women with freakishly large breasts. “He spoke about acts that he had seen in pornographic films, involving such matters as women having sex with animals, and films showing group sex, or rape scenes,” she testified. “On several occasions, Thomas told me graphically of his own sexual prowess.”

Thomas flat-out denied, under oath, repeatedly, that these conversations ever took place in his office with Hill or any other of his employees. “What I have said to you is categorical that any allegations that I engaged in any conduct involving sexual activity, pornographic movies, attempted to date her, any allegations, I deny. It is not true,” he said during questioning, along with specific denials like these:

Senator Hatch: Did you ever say in words or substance something like there is a pubic hair in my Coke?

Judge Thomas: No, Senator. …

Senator Hatch: Did you ever brag to Professor Hill about your sexual prowess?

Judge Thomas: No, Senator.

Senator Hatch: Did you ever use the term “Long Dong Silver” in conversation with Professor Hill?

Judge Thomas: No, Senator.

And: “If I used that kind of grotesque language with one person, it would seem to me that there would be traces of it throughout the employees who worked closely with me, there would be other individuals who heard it, or bits and pieces of it, or various levels of it,” Thomas said, as if daring the Senate committee to investigate further.

His bluff wasn’t called. Many individuals we uncovered who knew about Thomas’s habitual, erotically charged talk in the workplace were never contacted by the Senate Judiciary Committee or called as witnesses. We found three other women who had experiences with Thomas at the EEOC that were similar to Hill’s, and four people who knew about his keen interest in porn but were never heard from publicly. The evidence that Thomas had perjured himself during the hearing was overwhelming.

When our book came out, I was told there were lawyers in the Clinton White House and some congressional Democrats who, based on our reporting, were looking into whether Thomas could be impeached through a congressional vote. It’s not entirely without precedent: One Supreme Court justice, Samuel Chase, was impeached in 1804 for charges related to allowing his politics to infiltrate his jurisprudence — though he wasn’t ultimately removed, and that particular criticism looks somewhat quaint now. In 1969, Justice Abe Fortas resigned under threat of impeachment hearings for accepting a side gig with ethically thorny complications; the following year, there were hearings (which ended without a vote) against another justice, William O. Douglas, accused of financial misdealings. But when the Republicans took control of Congress after the 1994 midterms, the Thomas-impeachment idea, always somewhat far-fetched politically, died.

To my surprise, the notion of impeaching Thomas resurfaced during the 2016 campaign. In the thousands of emails made public during the FBI investigation of Hillary Clinton, there was one curious document from her State Department files that caught my attention, though it went largely unremarked upon in the press. Labeled “Memo on Impeaching Clarence Thomas” and written by a close adviser, the former right-wing operative David Brock, in 2010, the seven-page document lays out the considerable evidence, including material from our book, that Thomas lied to the Judiciary Committee when he categorically denied that he had discussed pornographic films or made sexual comments in the office to Hill or any other women who worked for him. When I recently interviewed Brock, he said that Clinton “wanted to be briefed” on the evidence that Thomas lied in order to be confirmed to his lifelong seat on the Court. He said he had no idea if a President Hillary Clinton would have backed an effort to unseat Thomas.

Unsurprisingly, the volume of sexual-harassment disclosures across so many professions recently has helped surface new, previously undisclosed information about Thomas’s predilection for bringing porn talk into professional settings. Late last year, a Washington attorney, Karen Walker, emailed New York. She had worked at the Bureau of National Affairs at the time of Hill’s testimony and said that a then colleague, Nancy Montwieler, who covered the EEOC for BNA’s Daily Labor Report, confided that Thomas had also made weird, sexual comments to her, including describing porn and other things he found sexually enticing. Montwieler, who considered Thomas a valuable source and didn’t think he was coming on to her, had invited him to a black-tie Washington press dinner, where he also made off-color remarks.

After Anita Hill came forward, Walker told me, she pressed Montwieler about whether she planned to speak up, but Montwieler brushed her off and said no, “because he’s been my source.” During the weekend of the Hill-Thomas hearings in October 1991, Walker called Montwieler again, begging her to say something. “I told her that what she knew could have helped Anita Hill,” Walker told me, as Senate Republicans tried to label Hill a liar and erotomaniac. “But she wanted to protect her source and said that if I said anything, she’d deny the whole thing.”

On a cold morning in early February, I knocked on the front door of Montwieler’s home in northwest Washington, D.C., where a wooden angel stands in the front yard. On the phone, when I summarized what Walker had told me, she said she didn’t want to talk about Thomas, but I hoped I could change her mind in person. Now retired from journalism, Montwieler, a petite woman with cropped hair and tinted glasses, was polite. She wouldn’t answer any questions about Thomas, but she never denied Walker’s account. Nor did she request that I keep her name out of this story. She simply said, “I’ll read it with interest.” Another colleague of Montwieler’s at BNA told me that her silence over the years isn’t surprising, given the value and cachet of knowing a powerful public official in Washington. (Update: After publication of this story, Montwieler emailed to say that “she never experienced any type of inappropriate behavior from [Thomas],” and that she did not “recall any conversations with Justice Thomas regarding inappropriate or nonprofessional subjects.” Montwieler had not disputed the allegations in the story during her two encounters with Abramson and three phone calls with a fact-checker.)

Thomas’s workplace sex talk was also backed up in 2010, nearly 20 years after the Hill-Thomas hearings, by Lillian McEwen, a lawyer who dated Thomas for years during the period Hill says she was harassed. She had declined to talk for Strange Justice but broke her silence in an interview with Michael Fletcher, then of the Washington Post, who had co-written a biography of Thomas. She said Thomas told her before the hearings that she should remain silent — as his ex-wife, Kathy Ambush, had. In another interview, McEwen told the New York Times that she was surprised that Joe Biden, the senator running the hearings, hadn’t called her to testify. In fact, she’d written to Biden before the hearings to say that she had “personal knowledge” of Thomas.

What sparked her to go public so many years later, McEwen told Fletcher, was a strange call Thomas’s wife, Ginni, made to Hill on October 9, 2010. On a message left on Hill’s answering machine, Ginni asked Hill to apologize for her testimony back in 1991. “The Clarence I know was certainly capable not only of doing the things that Anita Hill said he did, but it would be totally consistent with the way he lived his personal life then,” said McEwen, who by then was also writing a bodice-ripping memoir, D.C. Unmasked and Undressed. According to the Post, Thomas would also tell McEwen “about women he encountered at work and what he’d said to them. He was partial to women with large breasts, she said.” Once, McEwen recalled, Thomas was so “impressed” by a colleague’s chest that he asked her bra size, a question that’s difficult to interpret as anything but the clearest kind of sexual harassment. That information could also have been vital if made public during the 1991 confirmation hearings because it echoed the account of another witness, Angela Wright, who said during questioning from members of the Judiciary Committee that Thomas asked her bra size when she worked for him at the EEOC.

Neither Thomas nor his defenders came after McEwen for her story. Perhaps that was because of their lengthy past relationship. Probably, they wisely chose to let the story die on its own. But it’s what sparked Brock’s memo on the impeachment of Thomas.

The Thomas hearings were not just a national referendum on workplace behavior, sexual mores, and the interplay between those things; they were a typical example of partisan gamesmanship and flawed compromise. Chairman Biden was outmaneuvered and bluffed by the Republicans on the Judiciary Committee. He had plenty of witnesses who could have testified about Thomas’s inappropriate sexualized office behavior and easily proven interest in the kind of porn Hill referenced in her testimony, but had made a bargain with his Republican colleagues that sealed Hill’s fate: He agreed only to call witnesses who had information about Thomas’s workplace behavior. Thomas’s “private life,” especially his taste for porn — then considered more outré than it might be now — would be out of bounds, despite the fact that information confirming his habit of talking about it would have cast extreme doubt on Thomas’s denials.

This gentleman’s agreement was typical of the then-all-male Judiciary Committee. Other high-profile Democrats like Ted Kennedy, who was in no position to poke into sexual misconduct, remained silent. Republicans looked for dirt on Hill wherever they could find it — painting her as a “little bit nutty and a little bit slutty,” as Brock later said, with help from Thomas himself, who huddled with GOP congressmen to brainstorm what damaging information he could unearth on his former employee, some of which he seems to have leaked to the press — and ladled it into the Hill-Thomas testimony. Meanwhile, Biden played by Marquis of Queensberry rules.

Late last year, in an interview with Teen Vogue, Biden finally apologized to Hill after all these years, admitting that he had not done enough to protect her interests during the hearings. He said he believed Hill at the time: “And my one regret is that I wasn’t able to tone down the attacks on her by some of my Republican friends. ”

Among the corroborative stories — the potential #MeToos — that Biden knew about but was unwilling to use: those of Angela Wright; Rose Jourdain, another EEOC worker in whom Wright confided; and Sukari Hardnett, still another EEOC worker with relevant evidence. (“If you were young, black, female and reasonably attractive and worked directly for Clarence Thomas, you knew full well you were being inspected and auditioned as a female,” Hardnett wrote in a letter to the Judiciary Committee, contradicting Thomas’s claim “I do not and did not commingle my personal life with my work life” and supporting McEwen’s 2010 assertion that he “was always actively watching the women he worked with to see if they could be potential partners” as “a hobby of his.”) Kaye Savage, a friend of Thomas’s and Hill’s, knew of his extensive collection of Playboy magazines; Fred Cooke, a Washington attorney, saw Thomas renting porn videos that match Hill’s descriptions, as did Barry Maddox, the owner of the video store that Thomas frequented. And at least some members of Biden’s staff would have known Lillian McEwen had relevant information.

This is what any trial lawyer would call a bonanza of good, probative evidence (even without the additional weight of the other people with knowledge of Thomas’s peculiar sex talk, like Montwieler). In interviews over the years, five members of Biden’s Judiciary Committee at the time of the hearings told me they were certain that if Biden had called the other witnesses to testify, Thomas would never have been confirmed.

The most devastating witness would have been Wright. In addition to what she told the committee about Thomas’s comments on her breasts, she — upset by the experience — had also told her colleague Jourdain that Thomas had commented that he found the hair on her legs sexy. Jourdain, who came out of the hospital after a procedure just in time to corroborate Wright’s testimony and was cutting her pain medication in quarters so that she would be lucid, was never called to testify. Their accounts were buried and released to reporters late at night.

Wright would have killed the nomination. But Republicans, with faulty information spread by one of Thomas’s defenders, Phyllis Berry, claimed Wright had been fired by Thomas for calling someone else in the office a “faggot.” The man Wright supposedly labeled thus later said she never used the word, but Biden was too cowed to take the risk of calling her. Wright has since said repeatedly that she would have gladly faced Republican questioning. But in a pre-social-media age, that was that; the would-be witnesses weren’t heard from. Less than a week after the confirmation vote, Thomas was hastily sworn in for his lifetime appointment on the bench.

Most important to any new #MeToo reckoning of the Thomas case is Moira Smith’s Facebook account. She kept silent about what happened for 17 years. Her motives for going public appear identical to the ones expressed by the alleged victims of Harvey Weinstein, Charlie Rose, and other powerful, celebrated men: The time had come to bring sexual harassment, assault, and abuse of power into the open. “Donald Trump said when you’re a star, they let you do it; you can do anything. The idea that we as victims let them do it made me mad,” Smith told Coyle, the National Law Journal reporter. “Sure enough, Justice Thomas did it with I think an implicit pact of silence that I would be so flattered and starstruck and surprised that I wouldn’t say anything. I played the chump. I didn’t say anything.”

Going public has clearly not been an altogether happy experience for Smith. Almost immediately, the well-oiled Thomas defense machine — a cadre of friends, conservative lawyers, and former law clerks — swung into action. The Smith story was the first allegation involving Thomas’s behavior as a sitting justice, and thus had the potential to be especially troublesome. Almost immediately after Coyle’s story came a series of sharp attacks aimed at Smith by Carrie Severino, a former Thomas clerk, in the National Review. Undermining Smith’s credibility, calling her a “partisan Democrat,” and labeling her story “obviously fabricated,” Severino, who is policy director of the conservative Judicial Crisis Network, concluded, “The Left has a long track record of trying to destroy Justice Thomas with lies and fabrications, and these allegations are only their latest attempt. They should be ashamed of themselves.” Smith took down her Facebook profile, worried about right-wing trolls.

There are clear risks involved in speaking out against a Supreme Court justice. After Kaye Savage spoke to Mayer and me for Strange Justice, David Brock, who was then a staunch defender of Thomas’s, tried to, in effect, blackmail her. He threatened to make public details from her messy divorce and child-custody case if she did not sign a statement recanting what she had said to us for the book. Brock, who turned into a liberal Clinton supporter (and, of course, authored that memo about impeaching Thomas, in a rich bit of irony), told me in a recent interview that he got the personal information about Savage from Mark Paoletta, then a lawyer in the Bush White House (who had a recent stint as Vice-President Pence’s counsel) and a friend of Thomas. Brock believes it’s all but certain that Paoletta got the information about Savage directly from Thomas. (Paoletta has denied Brock’s account.)

Hill, who now teaches law at Brandeis University, was picked in December to lead a newly formed commission on sexual harassment in the entertainment industry; in a recent interview with Mayer for The New Yorker, she emphasized how crucial believability is to the narrative of cases like hers, and, in Mayer’s words, “Until now, very few women have had that standing.” Thomas, meanwhile, sits securely on the U.S. Supreme Court with lifetime tenure. He was 43 when he faced what he famously called “a high-tech lynching” before the Judiciary Committee. After that, he vowed to friends, he would serve on the Court another 43 years. He’s more than halfway there. His record on the Court has been devastating for women’s rights. Thomas typically votes against reproductive choice: In 2007, he was in the 5-4 majority in Gonzales v. Carhart that upheld the Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act of 2003. He voted to weaken equal-pay protections in the Court’s congressionally overruled decision in Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire. He joined the majority decision in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby, holding that an employer’s religious objections can override the rights of its women employees.

And, as Think Progress noted, “in one of the most underreported decisions of the last several years, Thomas cast the key fifth vote to hobble the federal prohibition on harassment in the workplace.”* The 5-4 decision in 2013’s Vance v. Ball State University tightened the definition of who counts as a supervisor in harassment cases. The majority decision in the case said a person’s boss counts as a “supervisor” only if he or she has the authority to make a “significant change in employment status, such as hiring, firing, failing to promote, reassignment with significantly different responsibilities, or a decision causing a significant change in benefits.” That let a lot of people off the hook. In many modern workplaces, the only “supervisors” with those powers are far away in HR offices, not the hands-on boss who may be making a worker’s life a living hell. The case was a significant one, all the more so in this moment.

Thomas, who almost never speaks from the bench, wrote his own concurrence, also relatively rare. It was all of three sentences long, saying he joined in the opinion “because it provides the narrowest and most workable rule for when an employer may be held vicariously liable for an employee’s harassment.”

The concurrence is so perfunctory that it seemed like there was only one reason for it: He clearly wished to stick it in the eye of the Anita Hills of the world.

This article appears in the February 19, 2018, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!

*Due to an editing error, the original version failed to attribute this quoted sentence to its author.