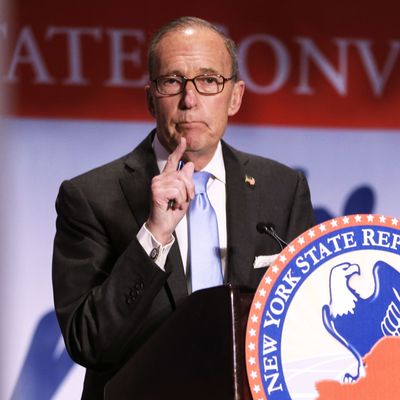

A dozen years ago, I wrote a book about the unshakable grip of supply-side economics upon the Republican Party. Supply-side economics is not merely a generalized preference for small government with low taxes, but a commitment to the cause of low taxes, particularly for high earners, that borders on theological. In the time that has passed since then, that grip has not weakened at all. The appointment of Lawrence Kudlow as head of the National Economic Council indicates how firmly supply-siders control Republican economic policy, and how little impact years of failed analysis have had upon their place of power.

The Republican stance on taxes, like its position on climate change (fake) and national health insurance (against it), is unique among right-of-center parties in the industrialized world. Republicans oppose higher taxes everywhere and always, at every level of government. In 2012, every Republican presidential candidate, including moderate Jon Huntsman, indicated they would oppose accepting even a dollar of higher taxes in return for $10 dollars of spending cuts. They likewise believe tax cuts are the necessary tonic for every economic circumstance.

The purest supply-siders, like Kudlow, go further and deeper in their commitment. Kudlow attributes every positive economic indicator to lower taxes, and every piece of negative news to higher taxes. While that sounds absurd, it is the consistent theme he has maintained throughout his career as a prognosticator. It’s not even a complex form of kookery, if you recognize the pattern. It’s a very simple and blunt kind of kookery.

In 1993, when Bill Clinton proposed an increase in the top tax rate from 31 percent to 39.6 percent, Kudlow wrote, “There is no question that President Clinton’s across-the-board tax increases … will throw a wet blanket over the recovery and depress the economy’s long-run potential to grow.” This was wrong. Instead, a boom ensued. Rather than question his analysis, Kudlow switched to crediting the results to the great tax-cutter, Ronald Reagan. “The politician most responsible for laying the groundwork for this prosperous era is not Bill Clinton, but Ronald Reagan,” he argued in February, 2000.

By December 2000, the expansion had begun to slow. What had happened? According to Kudlow, it meant Reagan’s tax-cutting genius was no longer responsible for the economy’s performance. “The Clinton policies of rising tax burdens, high interest rates and re-regulation is responsible for the sinking stock market and the slumping economy,” he mourned, though no taxes or re-regulation had taken place since he had credited Reagan for the boom earlier that same year. By the time George W. Bush took office, Kudlow was plumping for his tax-cut plan. Kudlow not only endorsed Bush’s argument that the budget surplus he inherited from Clinton — the one Kudlow and his allies had insisted in 1993 could never happen, because the tax hikes would strangle the economy — would turn out to be even larger than forecast. “Faster economic growth and more profitable productivity returns will generate higher tax revenues at the new lower tax-rate levels. Future budget surpluses will rise, not fall.” This was wrong, too. (I have borrowed these quotes from my book, in which Kudlow plays a prominent role.)

Kudlow then began to relentlessly tout Bush’s economic program. “The shock therapy of decisive war will elevate the stock market by a couple-thousand points,” he predicted in 2002. That was wrong. He began to insist that the housing bubble that was forming was a hallucination imagined by Bush’s liberal critics who refused to appreciate the magic of the Bush boom. He made this case over and over (“There’s no recession coming. The pessimistas were wrong. It’s not going to happen. At a bare minimum, we are looking at Goldilocks 2.0. (And that’s a minimum). Goldilocks is alive and well. The Bush boom is alive and well.”) and over (“The Media Are Missing the Housing Bottom,” he wrote in July 2008). All of this was wrong. It was historically, massively wrong.

When Obama took office, Kudlow was detecting an “inflationary bubble.” That was wrong. He warned in 2009 that the administration “is waging war on investors. He’s waging war against businesses. He’s waging war against bondholders. These are very bad things.” That was also wrong, and when the recovery proceeded, by 2011, he credited the Bush tax cuts for the recovery. (Kudlow, April 2011: “March unemployment rate drop proof lower taxes work.”) By 2012, Kudlow found new grounds to test out his theories: Kansas, where he advised Republican governor Sam Brownback to implement a sweeping tax-cut plan that would produce faster growth. This was wrong. Alas, Brownback’s program has proven a comprehensive failure, falling short of all its promises and leaving the state in fiscal turmoil.

The passage of the Trump tax cuts follow from the party’s “tax cuts über alles” philosophy. In the face of widespread social and economic problems, the one legislative goal the party could agree upon was reducing taxes paid by business owners. The existence of relatively high deficits even at the peak of the macroeconomic cycle did not deter them; indeed, Republicans — even moderates like Susan Collins — insisted the tax cuts would not increase the deficit. The onset of deficits exceeding a trillion dollars a year in the midst of low unemployment has not prompted any regret, or even a hint of willingness to compromise on the party’s rigid opposition to higher taxes.

This was the Trump agenda even with the relatively moderate Gary Cohn running the National Economic Council. Now that true believer Lawrence Kudlow is taking the helm, the dawn of fiscal sanity in the GOP is receding ever farther into the distant future.