Individual labor unions, like any organized constituency, sometimes have interests that conflict with the greater public’s. Police unions have an interest in protecting their officers from legal liability; the public, in ensuring that those who are supposed to “serve and protect” us have ample incentive not to shoot us dead. Coal miners’ unions have an interest in perpetuating their industry; the public, in perpetuating climatic conditions conducive to human life.

But these conflicts do not render organized labor — as a whole — a “special interest group” like any other. While certain unions may be an obstacle to the greater good on discrete issues, they are collectively a uniquely effective vehicle for realizing that good on the issues that matter most to working people.

Of course, Republicans have long denied this reality, insisting that their crusades against collective bargaining are a defense of the everyman’s “right to work” — rather than the corporate sector’s right to hold down wages. But as the labor movement declined over the second half of the 20th century — and the Democrats grew more reliant on corporate financing — even some of the party’s putative progressives found it convenient to see labor as a mere interest group whose priorities did not necessarily overlap with the broader public’s any more than those of “the business community.”

And many of the nation’s leading economists assured such Democrats that they were right: While unions were good for the workers in them, they limited opportunities for non-members — not least, African-American ones whom so many unions discriminated against. Meanwhile, by reducing flexibility in the labor market, unions sapped efficiency, and, thus, economic growth. Which is to say: They were institutions that redistributed wealth among workers — generally, in a regressive fashion, as high-skill workers were overrepresented in unions — while shrinking the overall economic pie that all working people had to share.

The core of this narrative is too discredited to need debunking. The simultaneous collapse of America’s private-sector unionization rate — and labor’s share of productivity gains — since the late 1970s, makes it difficult to deny that unions put some amount of upward pressure on wages for working people, as a whole; and the vast economic literature supporting that premise makes it impossible to do so.

Nonetheless, the ideas that unions impose a great toll on economic growth and always did far more to help high-skill and white workers, than low-skill and/or nonwhite ones have retained intellectual legitimacy.

Or, at least, they did — until the economists Henry Farber, Dan Herbst, Ilyana Kuziemko, and Suresh Naidu published their path-breaking new paper, “Unions and Inequality Over the Twentieth Century: New Evidence From Survey Data.”

Previous research into the questions of which workers benefited the most from unions in the United States has been undermined by limited data. The federal government only began tracking union status in its surveys in 1973, leaving much ambiguity about the composition of the unionized workforce before then. But in their reexamination of the relationship between unionization and inequality, Farber and his research partners were able to draw on Gallup survey data of union households dating all the way back to the 1930s.

That new tool — along with other innovations — helped the economists produce multiple, edifying findings:

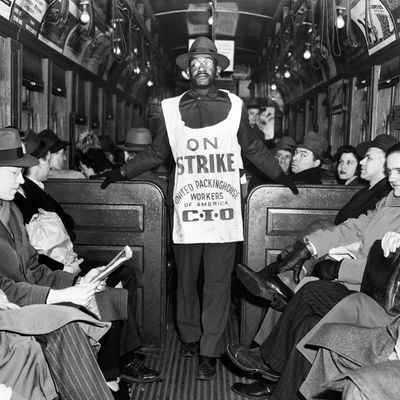

• When private-sector unionization was at its peak in the mid-1950s, low-skill workers and African-Americans made up a disproportionately high share of the unionized workforce. This means that, to the extent the “union premium” redistributes wealth between workers, this redistribution was progressive when unions were most prevalent.

• Regardless, unions primarily redistribute wealth from capital to labor as a whole: Private-sector unionization in the U.S. tightly correlates with lower levels of inequality, no matter what measure one uses (the Gini coefficient, 90-to-10 ratio, etc.).

• African-Americans secured a significantly higher wage premium by joining unions than whites. This shouldn’t be surprising, given that unions shield individual workers from exploitation — and without collective protections, black workers in the mid-century U.S. were especially vulnerable to abuse by their employers. Nevertheless, it’s a useful reminder that strengthening labor unions is a necessary plank of any serious agenda for racial justice in the United States — a point that often (understandably) gets obscured by the very real history of racism within the American labor movement.

• A higher unionization rate did not correlate with slower economic growth under any of the models that the researchers applied. This does not necessarily mean that unions did not — or cannot — have a negative influence on growth. But it does mean that there is little basis for assuming they inevitably have a large negative one. And that fact makes it extremely difficult to make a utilitarian case against encouraging higher rates of unionization, given labor unions’ demonstrable efficacy at increasing workers’ share of productivity gains.

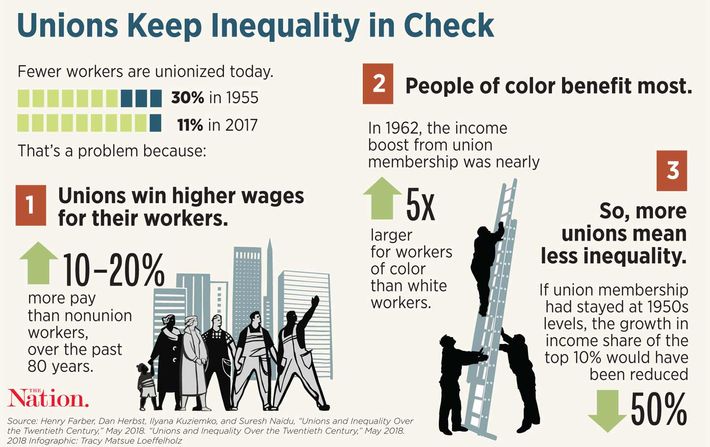

Mike Konczal’s excellent write-up of the study in the Nation features this handy visual distillation of its findings:

In sum: If Democrats want to put the greater good above special interests, they will prioritize the policy goals of organized labor next time they take power. If they want to put winning elections above all else, however, then they will do the exact same thing.