Elizabeth Warren hasn’t entered the 2020 race — but she’s already running her warm-up laps. The Massachusetts senator has been building up her foreign policy bona fides on the Senate Armed Services Committee, sending well wishes (and offers of resources) to Democratic candidates in Iowa and South Carolina, railing against Trump’s corruption in Reno, and whispering theories about how he can be dethroned in private talks with party bigwigs.

In 2016, Warren’s steadfast refusal to challenge Hillary Clinton — despite a grassroots campaign to draft her into that fight — led some to speculate that she simply had no interest in the Oval Office. It’s now clear that she does.

But in that, she’s far from alone. Just about every prominent Democrat seems to have “2020 vision”: Deval Patrick is imploring Democrats to “shout kindness” in the purple patches of Texas; Bernie Sanders is barnstorming for his revolution’s cadre; Cory Booker is eyeing a fall trip through the Deep South; and Kirsten Gillibrand is running (leftward) from her Blue Dog past at such accelerating speed, she may well be an anarcho-syndicalist by the time Iowa gets caucusing. Joe Biden, Kamala Harris, Steve Bullock, and John Hickenlooper are making their own preparatory noises, while dozens of others are monitoring the price of plane tickets to Des Moines.

Nevertheless, Warren’s moves have been especially assertive; so much so, they’ve triggered headlines about her prospective candidacy in the New York Times and Washington Post — and with them, poorly substantiated arguments about the populist wonk’s “electability,” or lack thereof.

The Times’ Jonathan Martin reports that some Democratic pooh-bahs see Warren as a more viable “populist” alternative to Bernie Sanders:

Perhaps most appealing to Democratic leaders, Ms. Warren might please their activist base while staving off a candidate they fear would lose the general election.

A candidate such as Mr. Sanders.

The 76-year-old Democratic socialist looms over the 2020 race, boasting an unmatched following among activists and a proven ability to raise millions of dollars online. Having pushed policies like single-payer health care and free public college tuition into the Democratic mainstream, Mr. Sanders could be a powerful competitor for the nomination — and a daunting obstacle to Ms. Warren and other economic populists.

But for all the evident support for Mr. Sanders’s policy ideas, many in the party are skeptical that a fiery activist in his eighth decade would have broad enough appeal to oust Mr. Trump.

Meanwhile, the centrist think tank Third Way warned the Post that Warren could give Trump a second term:

Groups like the Democratic think tank Third Way, which has tangled with Warren in the past, have argued that the ideas of the party’s liberal populists will make it harder to elect a Democrat in 2020, since they could confirm a perception, especially among swing voters, that the party is anti-business and overly focused on helping the poor.

“Democrats have struggled with the jobs issue for almost a decade, and the party was not equipped to challenge Donald Trump’s zealous pro-jobs message in 2016,” one Third Way analysis concluded last year, based on focus groups.

Both of these arguments are dubious.

As David Shor of Civis Analytics notes, there is little empirical evidence that Warren would make a stronger general election candidate than Sanders — but quite a lot to suggest the opposite. The Vermont senator’s national approval rating hovers around 56 percent, while Warren’s lies under 40. Sanders’s favorability numbers in Vermont (which is to say, with the constituents who know him best) are far higher than the state’s partisan breakdown would predict; Warren’s home-state favorability, by contrast, is roughly equal to what one would expect a generic Democratic senator to boast in Massachusetts — and her approval rating is also decidedly lower than that of her colleague Ed Markey. And although they have relatively little predictive value, in polls of hypothetical 2020 matchups, Sanders reliably performs better against Trump than Warren does.

None of this means that Sanders would necessarily be the stronger general election candidate. Bernie spent part of the 1980s as an elector for a Trotskyist political party; Warren spent that decade as a Reagan Republican. Thus, GOP ad makers should have an easier time painting Sanders as a traitorous pinko. Plus, the man will be pushing 80 years old in 2020 — there’s a genuine risk that he could die during the campaign’s homestretch.

Still, it isn’t the case that all nonquantitative considerations redound to Warren’s benefit. There is cause to suspect that an aging, angry white man — with a talent for projecting authenticity — might be an easier sell to Rust Belt swing voters than a professorial, professional-class woman. And then, there’s the maddeningly plausible possibility that Trump’s “Pocahontas” smear may actually be an effective political attack.

All of which is to say: While it is possible that Warren would be the stronger general election candidate, the evidence for that proposition is so weak, it’s hard to believe that any neutral observer would strongly endorse it.

It’s quite easy, by contrast, to see why some Democratic leaders would simply like Warren better than Sanders. For one thing, the former is actually a member of their party, and spends much less time railing against its “Establishment.” For another, she is much better versed on the details of policy than Sanders is, and boasts a more conventionally meritocratic background.

Similarly, Third Way’s claim that Democrats would be best served by nominating a “pro-business” candidate in 2016 is so unsubstantiated — and ideologically convenient for an organization that exists to promote “pro-business” progressivism — that it’s impossible to take seriously.

Electability arguments have always been handy stalking horses for substantive disagreement. But in previous cycles, there was some plausibility to the idea that party pooh-bahs could identify in advance which candidate was most likely to prevail in November.

In the age of Trump, this just isn’t so. If mocking prisoners of war and the disabled — and bragging about adultery and pussy-grabbing — do not necessarily render one “unelectable,” it’s impossible to believe any Democratic operative who says with certainty that a honeymoon in the Soviet Union does.

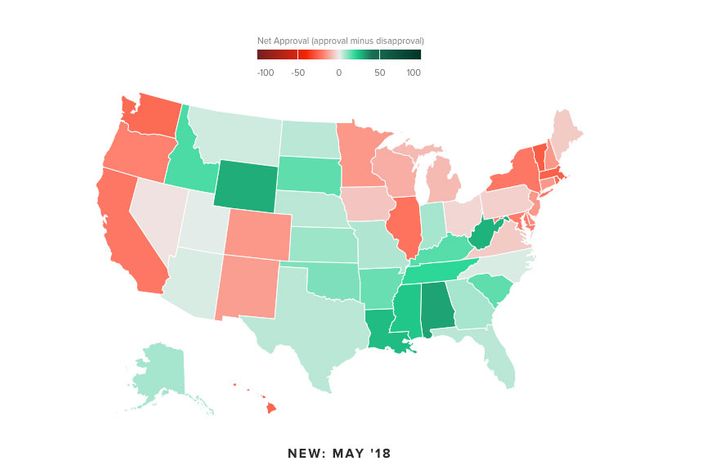

Separately, all available evidence suggests that it won’t actually matter that much how “electable” the Democrats’ 2020 nominee is. Donald Trump entered office as the most unpopular president-elect in American history. Since then, his approval rating has declined in all 50 states; in the Midwest battlegrounds of Pennsylvania, Michigan, Wisconsin, Iowa, and Ohio, his favorability is now net negative. In hypothetical 2020 polls, Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders lead Trump by double digits; while Warren and less prominent Democrats best him by smaller, but still comfortable, margins.

Which is to say: At the height of an economic expansion, with unemployment sitting near historic lows, Donald Trump is poised to lose reelection in a landslide.

A lot can change in two years. But some important things, like macroeconomic conditions, are more likely to change in ways that hurt Trump than in ones that help him. And if current trends persist, and Democrats take the House this fall, their oversight will ensure that the second half of Trump’s first term will be even more plagued by scandal that its current one. Meanwhile, the demographic changes that have helped Democrats win the popular vote in six of the last seven elections are only accelerating — millennials will constitute a larger share of the voting-eligible population in 2020 than baby-boomers.

It took a confluence of low-probability developments — the Comey letter, Russian hacking, a last-minute hike in Obamacare premiums, and the presence of two (relatively well-funded) third-party candidates — to put Trump into the White House. In all probability, it will take only a minimally politically competent Democrat to get him out. (This is largely why the Democratic field is already so thickly crowded.)

Thus, in the 2020 Democratic primary, electability arguments will be less credible and relevant than in any such race in recent memory. But the incentives for making bad faith electability claims will be as high as ever: Given the high probability that the party’s nominee will prevail in November, Democratic operatives of all stripes will be free to pretend that the true key to victory is adopting all of their policy preferences.

Barring a sharp change in the political winds (or Trump’s removal from office), Democratic voters should ignore such punditry, and simply vote for whichever candidate they would most like to be president.