America’s unemployment rate is hovering near half-century lows. There are now more job openings than unemployed workers in the United States for the first time since the government began tracking that ratio. For America’s working class, macroeconomic conditions don’t get much better than this.

And yet, most Americans’ wages aren’t getting any better, at all. Over the past 12 months, piddling wage gains — combined with modest inflation — have left the vast majority of our nation’s laborers with lower real hourly earnings than they had in May 2017. On Wall Street, the second-longest expansion in U.S. history has brought boom times — in the coming weeks, S&P 500 companies will dole out a record-high $124.1 billion in quarterly dividends. But on Main Street, returns have been slim.

Economists have put forward a variety of explanations for the aberrant absence of wage growth in the middle of a recovery: Automation is slowly (but irrevocably) reducing the market-value of most workers’ skills; a lack of innovation has slowed productivity growth to a crawl; well-paid baby-boomers are retiring, and being replaced with millennials who have enough experience to do the boomers’ jobs — but not enough to demand their salaries.

There’s likely some truth to these narratives. But a new report from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) offers a more straightforward — and political — explanation: American policymakers have chosen to design an economic system that leaves workers desperate and disempowered, for the sake of directing a higher share of economic growth to bosses and shareholders.

The OECD doesn’t make this argument explicitly. But its report lays waste to the idea that the plight of the American worker can be chalked up to impersonal economic forces, instead of concrete political decisions. If the former were the case, then American laborers wouldn’t be getting a drastically worse deal than their peers in other developed nations. But we are. Here’s a quick rundown of the various ways that American workers are getting ripped off:

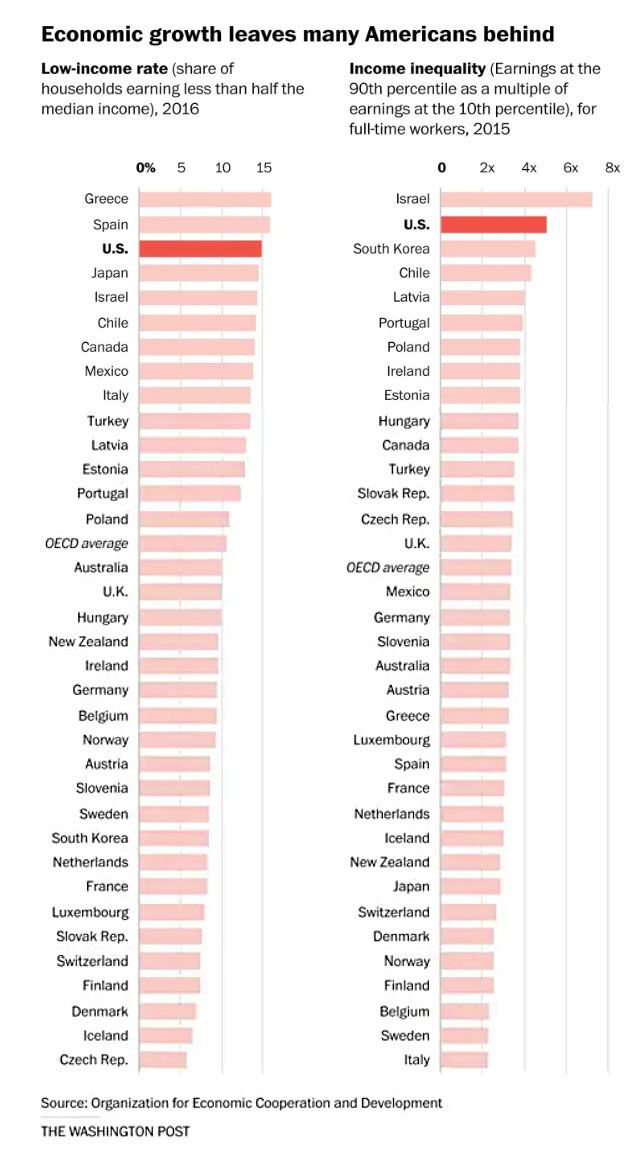

American workers are more likely to be poor (by the standards of their nation). In the United States, nearly 15 percent of workers earn less than half of the median wage. That gives the U.S. a higher “low-income rate” than any other developed nation besides Greece and Spain.

We also get fired more often — and with far less notice. Roughly one in five American workers leave their jobs each year, a turnover rate higher than those in all but a handful of other developed countries. And as the Washington Post’s Andrew Van Dam notes, that churn isn’t driven by entrepreneurial Americans quitting to pursue more profitable endeavors:

[D]ecade-old OECD research found that an unusually large amount of job turnover in the United States is due to firing and layoffs, and Labor Department figures show the rate of layoffs and firings hasn’t changed significantly since the research was conducted.

Not only do Americans get fired more than other workers; we also get less warning. Every developed nation besides the U.S. and Mexico requires companies to give individual workers at least a week’s notice before laying them off; the vast majority of countries require more than a month. But if you’re reading this from an office in the U.S., your boss is free to tell you to pack your things at any moment.

Our government does less for us when we’re out of work than just about anyone else’s. Many European countries have “active labor market policies” — programs that provide laid-off workers with opportunities to train for open positions. The United States, by contrast, does almost nothing to help its unemployed residents reintegrate into the labor force; no developed nation but Slovakia devotes a lower share of its wealth to such purposes. Meanwhile, a worker in the average U.S. state will stop receiving unemployment benefit payments after they’ve been out of a job for 26 weeks — workers in all but five other developed countries receive unemployment benefits for longer than that; in a few advanced nations, such benefits last for an unlimited duration.

Labor’s share of income has been falling faster in the U.S. than almost anywhere else. Between 1995 and 2013, workers’ share of national income in the U.S. dropped by eight percentage points — a steeper decline that in any other nation except for South Korea and Poland.

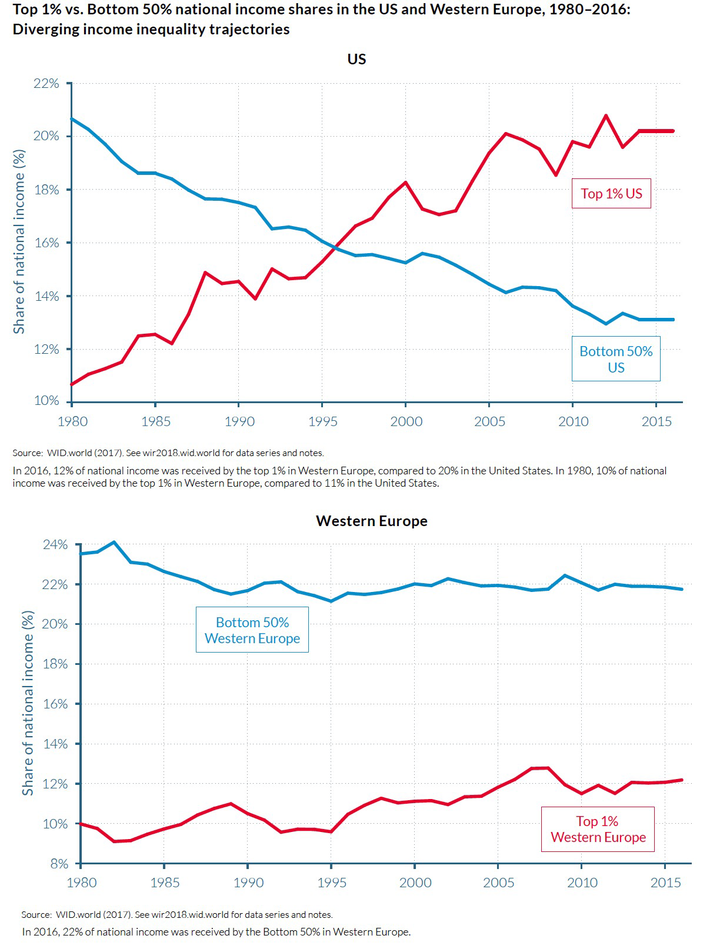

And the American capitalist class has been claiming an exceptionally high share of national income for much longer than just two decades — as this stunning chart from the 2018 World Inequality Report makes clear:

Given all this, it seems safe to say that America’s aberrantly weak wage growth is (at least in part) the product of political decisions made at the national level. A government that provides its unemployed with unusually limited job training and benefits is one that has chosen to make it riskier for workers to demand higher wages on the threat of quitting.

Further, the OECD finds that only Turkey, Lithuania, and South Korea have lower unionization rates than the United States, a fact that can be attributed to the myriad ways American policymakers have undermined organized labor since the Second World War. And a government that discourages unionization — and alternative forms of collective bargaining — is one that has decided to cultivate an exceptionally large population of “low income” workers, and an exceptionally low labor-share of national income.

President Trump spends a great deal of time and energy arguing that American workers are getting a rotten deal. And he’s right to claim that Americans are getting the short end. But the primary cause of that fact isn’t bad trade agreements or “job killing” regulations — its the union-busting laws and court rulings that the president has done so much to abet.