In recent years, there’s been a vigorous debate among American political scientists about just how thoroughly rich people dominate U.S. policy-making.

In 2014, Martin Gilens and Benjamin Page published a study that suggested “economic elites” and “business interests” enjoy such disproportionate influence over which policies the federal government enacts, America scarcely qualifies as a popular democracy. Other political scientists contested this conclusion, arguing that the underlying data was more ambiguous. Among other things, they noted that, according to Gilens and Page’s own research, when the middle class and the rich disagreed about a given bill, Congress took the former’s side 47 percent of the time.

One might find this rebuttal less than reassuring. After all, the fact that a fraction of wealthy Americans only succeed in vetoing majoritarian preferences a little over half the time isn’t the most compelling proof of our democracy’s vitality. But there was another flaw in the critiques of Gilens and Page’s analysis (one common to the original study, and which might, admittedly, be unavoidable): By measuring the responsiveness of American policymakers on the basis of survey data and congressional activity, they failed to account for the role that elite influence plays in determining what policy positions are deemed serious enough to ask voters about, let alone, to write into congressional legislation.

Ignoring this aspect of the policy-making process is all-but certain to understate the political influence of economic elites — because such influence plays a major role in determining what policy positions make it into the national debate in the first place.

New public opinion research from Data for Progress (DFP) spotlights this reality. In partnership with Yougov Blue, the progressive think tank polled a variety of left-wing economic policy ideas that have long been deemed too radical to merit pollsters’ attention or congressional scrutiny. Some of these ideas have recently won the support of the Democratic Party’s most left-wing lawmakers; others lie beyond the bounds of Bernie Sanders’s political imagination.

And virtually all of them are more popular than the mainstream Republican Party’s economic agenda.

Take government drugs (…please): DFP and YouGov asked voters, “Would you support or oppose having the government produce generic versions of life-saving drugs, even if it required revoking patents held by pharmaceutical companies?”

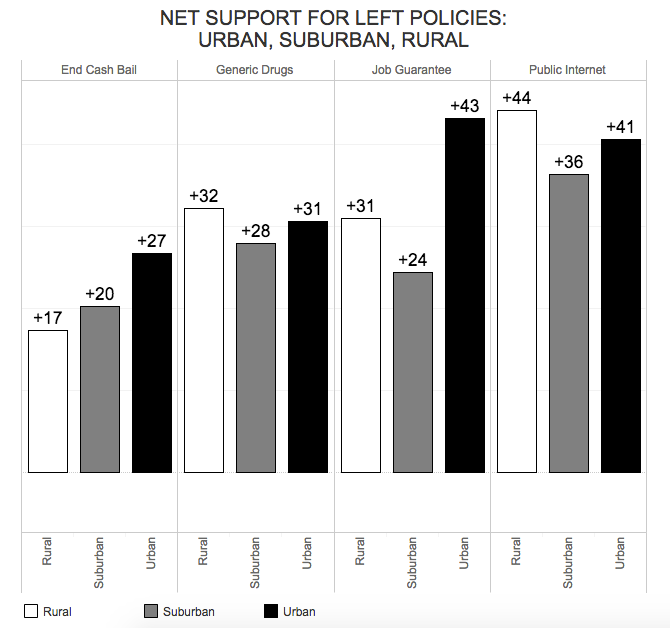

Respondents approved of that idea by a margin of 51 to 21 percent. The proposal enjoyed the approval of a majority of Trump voters, and actually garnered more support in (stereotypically conservative) rural zip codes than in urban ones.

The fact that this policy option has garnered approximately no interest in Washington — and thus, has not been extensively polled — cannot be attributed to its lack of popular support. In fact, the federal government’s failure to take action on the idea can’t even be attributed to gridlock or intransigent Republicans. As a team of medical and legal scholars from Yale and Harvard University explained in a 2016 Washington Post op-ed, the Executive branch already has the legal authority to unilaterally override patent law:

In expanding a railroad or airport…[t]he government can use its power of eminent domain…to acquire the land for a reasonable price. When expanding access to important new medicines, the response, as two of us argue in an article in this month’s edition of the journal Health Affairs, should be similar. The government should employ an analogous power — government patent use — to negotiate lower prices, or buy low-cost, generic versions of drugs for use in government programs. This is possible because existing law gives the federal government limited immunity to challenges from patent holders: Patent holders cannot stop the government from making or buying products that infringe on their patents, and can sue only for reasonable compensation.

Federal agencies have previously relied on this mechanism to purchase items produced by companies other than the patent holders, ranging from lead-free bullets to electronic passport readers.

As the price of new hepatitis drugs was skyrocketing in 2016, the Obama administration had the power to override privately held patents and order the production of generic versions of the breakthrough pharmaceuticals. All available evidence suggests that there would have been broad public support for such a move (to the extent that Republican voters’ were prepared to approve of anything Obama did, anyway). The fact that this was never even discussed is a reflection of the pharmaceutical lobby’s influence, not the American public’s deep belief in the inviolability of intellectual property rights.

The DFP surveys further documents overwhelming support for “the creation of a publicly-owned internet company to fill coverage gaps in rural, urban, or remote areas that currently lack robust Internet access.” Some 56 percent of voters support that concept, while just 16 percent oppose. Trump voters and rural Americans both support this “big government” takeover of internet provision — net approval of the policy among rural voters was a whopping 44 percent.

What’s more, 55 percent of voters supported “the federal funding of community job creation for any person who can’t find a job,” with backing for that drastic expansion of public-sector employment once again strong in both urban and rural areas. Ending cash bail also enjoyed strong backing throughout the country.

Some municipalities do provide public broadband. And some Democratic lawmakers have recently signed onto job-guarantee proposals. But these ideas still remain at the fringes of congressional opinion and public debate, despite their ostensible appeal with the fabled “median voter.” It is hard to believe that this fact has nothing to do with the influence of telecom firms on Capitol Hill, nor that of affluent voters who do not want to subsidize public job creation with their tax dollars.

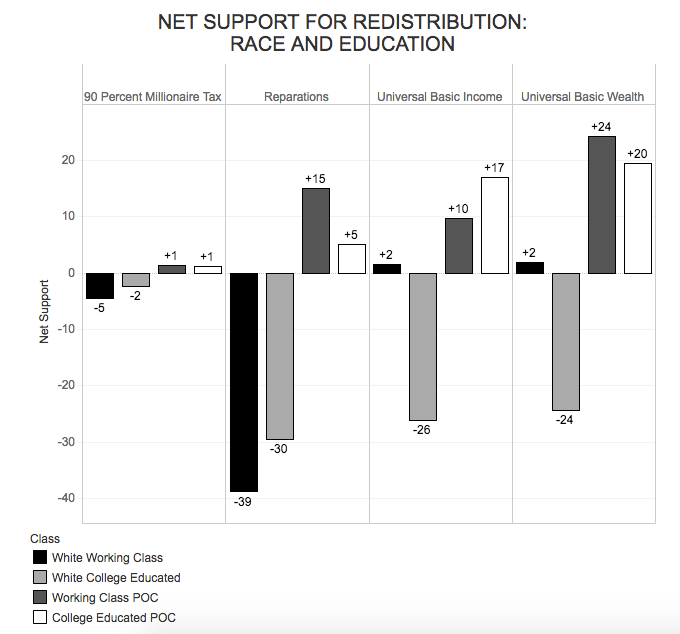

Arguably though, DFP’s most telling finding concerns a left-wing policy that is, in fact, a bit too radical for majoritarian tastes. In the think tank’s survey, respondents opposed a 90 percent tax rate on all income above $1 million by a margin of 40 to 33 percent. This suggests that public opinion on tax policy has genuinely drifted rightward since Eisenhower’s heyday. And yet, it also demonstrates that a 90 percent top tax rate — which is to say, one nearly twice as high as the top rate proposed by Bernie Sanders — is still more in line with American public opinion than the tax policies of mainstream Republican politicians.

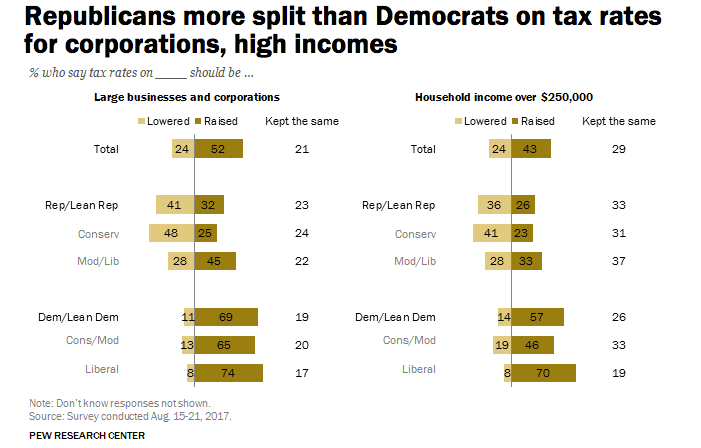

In DFP’s poll, voters opposed a 90 percent top tax rate by a 7-point margin; in Pew Research polling from August of last year, voters opposed lowering taxes on corporations by a 49-point margin, and opposed cutting taxes on households that earn more than $250,000 by a 48-point one.

Nevertheless, the idea of cutting taxes on the rich is “mainstream” enough to be a perennial subject of opinion polling, while the idea of a de facto “maximum income” is not — and, of course, America’s governing political party decided to make giant tax cuts for the rich and corporations its No. 1 legislative priority last year, while no lawmaker in either party introduced legislation aimed at reinstating a 90 percent top marginal tax rate. It is hard to explain why this would be the case without positing that the rich enjoy wildly disproportionate influence over our nation’s political debate.

Or, to put a finer point on the matter: It is virtually impossible to comprehend how the U.S. Congress could have spent most of 2017 trying to pass regressive tax cuts and draconian reductions in federal health-care spending — amid overwhelming public opposition among Republican voters, and a literal public-health emergency concentrated in GOP-controlled regions of the country — without stipulating that economic elites and business interests currently dominate the American political system.

Which isn’t to say that such dominance is inevitable. The inequitable distribution of wealth, political knowledge, and free time in the United States gives wealthy individuals and corporations a leg up on ordinary Americans in the fight to influence public policy. But ordinary Americans have strength in numbers. And as DFP’s polling suggests, there are no small number of progressive economic policies that a large majority of working people (from a wide array of regions, religious backgrounds, and ethnic groups) are ready to rally around. The trick is building institutions — and cultivating political leaders — that are willing and able to get that rally started.