Driving around Newburgh in August, I got the sense that some kind of change is going on. There’s a cluster of new stores (an apothecary, a bike museum ) and restaurants (organic-leaning ones) that have opened on the town’s main drag, Liberty Street, and renovation projects everywhere — all this alongside stretches of abandoned and condemned buildings. The contrasts can be disorienting — this is, after all, a city whose most recent claim to fame was being named the murder capital of the state. And changes like these are happening in other previously overlooked towns up the river too, like Catskill and Troy. It’d be too easy to declare any of these places a potential “next Hudson” — the onetime working-class town where antique lamps now go for $7,000. Hudson’s about-face, which resulted in longtime residents being priced out, has become a kind of cautionary tale for these developing small towns, which, after struggling through decades of decline, are showing glimmers of a turnaround and are intent on growing in a different way. Many newcomers (mostly artists at this point, drawn to the incredibly affordable, stately housing stock and growing creative communities) are moving in full time, not just weekending, and are looking to really settle down and contribute. But how this all plays out is anyone’s guess. As lifelong Newburgher Lillie Bryant Howard warns, “Just look at what happened in Brooklyn.”

Newburgh

1¼ hours from the city

Cheap Victorians, curated knickknack shops, and Honduran-style pollo frito.

Where the Designers of Central Park Got Their Start

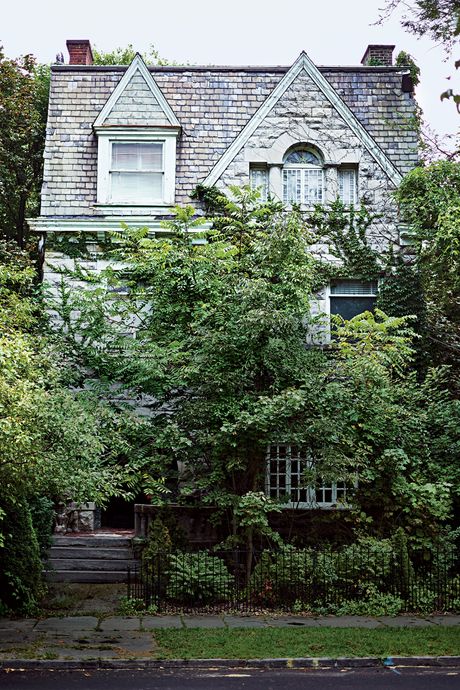

It was here, in a little stone house beside the Hudson, that George Washington oversaw the end of the Revolutionary War. By the mid-19th century, Newburgh was home to some of the major architects and landscape designers of the era, among them Andrew Jackson Downing, a native Newburgher who opened a firm here and inspired Calvert Vaux, Frederick Law Olmsted, and Frederick Clarke Withers to build in town. The result is an incredibly charming mix of Greek Revival, Romanesque, Carpenter Gothic, Queen Anne, and High Victorian buildings and rowhouses (some preserved, some, sadly, less so). Newburgh, like so many towns along the Hudson, was a big manufacturing hub in the early-20th century, though when the Thruway was opened in the ’50s and the bridge to Beacon in 1963, they drew people away from the once-bustling downtown. After a series of failed urban-renewal projects in the ’60s and ’70s, the city lost over a thousand historical buildings, displacing a large number of the African-American families (many of whom had moved to town during the Great Migration), who made up a third of the population. Years of blight followed, along with a rise in poverty and crime. By 2010, Newburgh had one of the highest crime rates in the state. It’s now at a ten-year low.

For Sale

New Newburgh

“We have a barbecue every year. Every time, a few people decide to come back and buy a place.”

After many false starts and some (maybe) comebacks, documented as early as 1986 by the New York Times (“Newburgh Tries to Recapture Its Past Glory,” reads the headline), the city has started to show actual signs of a reawakening, fueled in part by a rising arts scene. Of course, the initial wave of newcomers was from Brooklyn. “First, it was a large contingent of people from Clinton Hill and Fort Greene, later Red Hook, then Park Slopers,” says Hannah Brooks, a doctor and Clinton Hill expat, now a full-time Newburgher. “We have a barbecue every year, inviting friends up from the city,” says James Holland, a filmmaker who moved from Williamsburg in 2014 with his girlfriend, Kelly Schroer, who eventually left behind a job at David Zwirner gallery and now runs a local arts nonprofit called Strongroom. “Every time, a few people decide to come back and buy a place.” Word spread that you could get a building for a couple thousand bucks, either directly through the city or the Newburgh Community Land Bank — founded in 2012 and funded in large part by 2008 mortgage-crisis funds, it helps rehabilitate many of the city’s abandoned buildings. The Land Bank also works with Habitat for Humanity, creating home-ownership programs that prioritize longtime Newburgh residents, and sponsors a residency called Artist in Vacancy, which lets artists make use of empty buildings before they become homes again. You can now regularly find inexpensive studio space in Newburgh on the upstate tab of the weekly online real-estate newsletter Listings Project, a good barometer for where the creative-ish people are moving. Newburgh Open Studios, which takes place the last weekend in September and is now in its eighth year, was started by photographer Michael Gabor and his partner, painter Gerardo Castro, who also run Newburgh Art Supply. “The first year, we just had 11 artists, including the two of us,” says Castro. “This year, we’ll have over 100.” All this is happening alongside a growing Latino community that makes up more than half of the city’s population; Ecuadoran and Peruvian restaurants are opening throughout Newburgh, which recently declared itself a sanctuary city. But outside speculators are starting to circle — a cause for concern among residents new and old. “I don’t feel that excited about what’s going on,” says Lillie Bryant Howard, a 78-year-old jazz singer, political activist, and lifelong resident. “There are a lot of minorities in this city that are not able to have a decent life. Newburgh has to grow in the right way.”

A Lot’s Happening on Liberty Street

On Newburgh’s longest block, new boutiques and eateries are sidling up to longtime barbershops and other veteran storefronts.

Liberty Street is a mix of old and new, particularly the cluster of businesses near Washington’s headquarters. Recent addition Velocipede, a bike museum, is next door to Flour Shop, a bakery that opened in late August. There’s the Ms. Fairfax restaurant, an airy, minimalist space that opened a couple years ago and serves shakshuka eggs and brick chicken. A few doors down is another late-August entry, Field Trip, an apothecary/general store with badminton racks adorning its storefront. Across the street, adjacent to newly opened men’s shop M. Lewis, is Razor Sharp barbershop, a Liberty institution for 14 years. Other mainstays include custom-sign store Design by Sue (1981), Hip-Hop Heaven (1999), and Liberty Locksmith (2003). Maybe most symbolic of Liberty Street’s transformation is Seoul Kitchen, a Korean restaurant that relocated here two years ago, after being priced out of Beacon.

Christina Silvestris, owner of Field Trip, where rosemary-mint soap goes for $7. On Liberty Street since late August: “I have a skin-care line, Hudson Naturals, and I’m carrying other makers from Portland, Minnesota, all over. I wanted to bring it all to Newburgh. I just love the energy that’s going on right now here. I know a lot of people get scared of Newburgh, but I don’t know — there’s this resurgence of all these artists coming here. We’ve lived everywhere from Hudson to Cold Spring to Kingston. I didn’t want to hop into a trendy town; I wanted to be a part of something, help it come back.”

Kendew, owner of Razor Sharp barbershop, where a shave goes for $10 and a men’s haircut for $15. On Liberty Street since 2004: “There were a lot of empty storefronts before — mostly a write-off, waiting for Newburgh to pop. Now everyone’s opening businesses. There was a church I used to go to; now it’s a bicycle [museum]. I feel like the landlords pushed them out. I welcome all the businesses here, that’s the only thing that bothered me. I think they want it to be like Beacon. Prices are going up. Down in the barbershop, I hear everything. Some stuff is good, some is bad. Also the parking is bad. It’s like Manhattan; I can’t find a spot.”

Locals’ To-Do List

“Illuminated Festival, which we have every summer, is about telling folks in the Hudson Valley who have really negative feelings about this place, bringing them in to spend a day, to take another look, resee our architecture, resee what the community has to offer.” —Paul Ernenwein, lawyer

“I love North Plank Road Tavern. It’s an old-school place that has really good food — like steamed mussels and braised pork shoulder — kind of on the edge of the city before the bridge to Beacon. Solidly good. Those people have been here forever, and they get kind of overlooked with all the new things coming in.” —James Holland, filmmaker

“I feel like between The Wherehouse and Ms. Fairfax, there’s no favorite bar. We swap back and forth. We never leave one of them empty for the night.” —Melzina Canigan-Izzard, carpenter and volunteer firefighter

“The pollo frito estilo Honduras from Zulimar and the carne asada from Guatemalan café El Chapin are great. Try them if you can.” —Bill Conyea, tech recruiter and Newburgh small-business investor

“Downing Park was designed by Olmsted and Vaux, so it feels like a microversion of Central Park. Shelter House Café, which looks out over the pond, is bringing more people to the park. I like to come after work with my dog, sit out here with a glass of wine.” —Kelly Schroer, arts-nonprofit Director

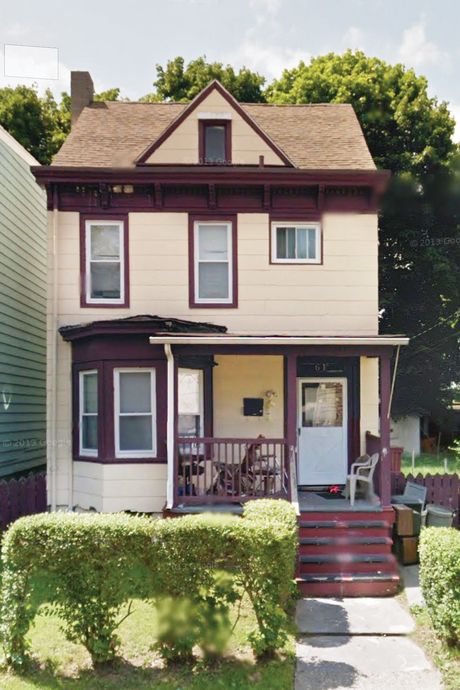

What $11,400 Gets You

How much it actually costs to bring a brick rowhouse in Newburgh back to life.

In March 2016, John Zelehoski, a skateboarder who works in art and production, bought a 1900 three-bedroom, two-story building from the Newburgh Community Land Bank for $11,400. Here’s what he had to put into it to make it livable.

The work already done by Land Bank

$67K: “New EPDM roof, basement clean-out, new concrete foundation, testing and remediation of lead and asbestos, new electrical meter. Somehow it still felt like starting from scratch.”

The demo

$5K: “Tearing down walls, exposing and fixing structural issues. I hired my neighbors from the block for demo. I probably said ‘Last dump run’ six times before my actual last dump run.”

The construction

$20K each on electrical and plumbing: “I hired professionals.”

$700 for skylights: “They were quoted at $2K. My dad, mom, and brother helped with floors, doors, and skylights.”

$4K for floors: “Doing the work myself usually ended up costing about a third of what I was quoted.”

$2K for framing: “I was quoted $6K; architect friends helped with this.”

$15K on two kitchens and two bathrooms: “I tore out everything and built from scratch.”

The roadblocks

“Right when I was hoping to get my certificate of occupancy, a project inspector told me I had to replace the front-entry stairs, which required demo, drawings, and approval, on top of construction.

I restored the original front-entry double doors but broke the piece of glass, lost my temper, and punched the door. Wearing a cast for two months forced me to take a much-needed break.”

Catskill

2½ hours from the city

Rehabbed waterfront factories, contemporary-dance performances, and doughnuts made from scratch.

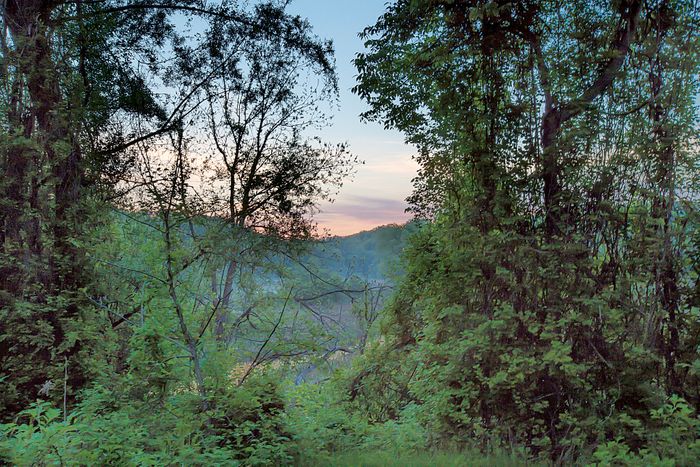

The Hudson River School Originated Here

As in many a 19th-century town on the Hudson, the river drove a lot of the industry in Catskill. Clearly inspired, the artist Thomas Cole moved here in 1836 and began the Hudson River school of landscape painting. Proximity to the water also allowed local vendors to harvest ice, which was scooped from the Hudson and shipped down to New York City. The once-sleepy town features Catskill Creek, a tributary of the river that snakes its way past former factories that have been restored and repurposed — a recent change that locals welcome.

For Sale

New Catskill

“Just five years ago, on a Saturday nothing was open.”

I think what’s important about this place is it hasn’t quite figured out yet how cool it can be,” says designer John Schlotter, who manufactures the clothing line Artists & Revolutionaries in Catskill. He opened his store in Hudson but moved into a live-work space here about a year ago for less rent. The consensus from him and other locals is that the town took a turn in the past few years. “Just five years ago, you would go down to Catskill on a Saturday and nothing was open,” says Susan DeFord, a real-estate agent who moved up from Park Slope. Another Brooklyn transplant is Rob Kalin, the founder of Etsy, who purchased a few buildings here. In 2015, he and other local parents opened a cooperative school in town called Catskill Wheelhouse. With a steady stream of musicians, sculptors, and writers — and their spawn — headed to Catskill, along came the new mixed-use art spaces: There’s Lumberyard, a performing-arts studio, which begins its first season this month, and Foreland, an 1840s mill building repurposed into studios, a gallery, and a restaurant, that’s set to open in 2019. Foreland is run by Stef Halmos, an artist from Brooklyn who moved here a year ago, after buying the 50,000-square-foot waterfront property. She envisions artists using the space to expand a show upstate or having visitors come by to sit down for a coffee after an exhibit. “Catskill wants to develop differently than Hudson,” says Halmos. “Where it’s accessible to everyone, where people can still buy homes. Whether that’s a possibility in ten years it’s hard to tell, but for now that’s very much the intention.”

Locals’ To-Do List

“Gracie’s Luncheonette is Catskill’s answer to Phoenicia Diner — really good doughnuts. It’s in Leeds, a small hamlet of Catskill.” —Susan DeFord, real-estate agent

“Circle W is a little general store that also does breakfast and lunch, and sometimes they have live music in the barn.” —S.D.

“HiLo is the coffee shop everyone goes to. They’re constantly curating cool things in their space. I spend a lot of time there; they’ve really galvanized the creative community in town.” —Stef Halmos, artist

“Captain Kidd’s is a pirate-themed bar — plastic statues of pirates everywhere — in this old, historic building. It’s really weird.” —John Schlotter, Designer

“There’s a great place on Main Street, New York Restaurant, sort of modern Polish food. It’s warm and sophisticated.” —S.D.

“I eat dinner at La Conca D’Oro twice a week. This Italian place, old-school Mafia vibe, big plates of food — hasn’t changed.” —J.S.

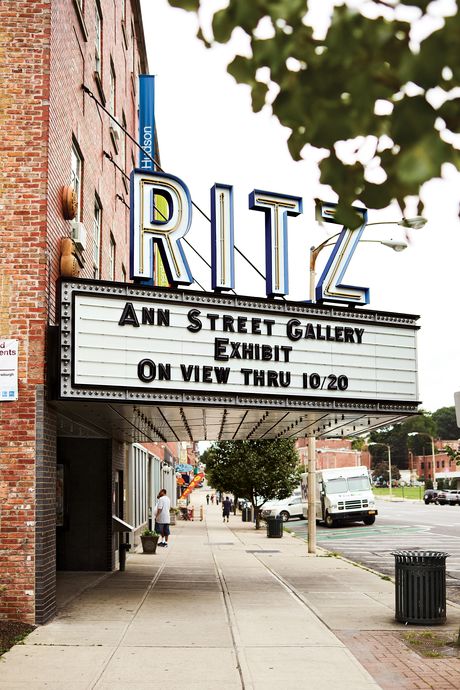

Troy

3 hours from the city

Gothic churches turned galleries, farm-to-table Korean food, and a standout Greenmarket.

It Was Once a Steel Town

Slightly farther afield, about 140 miles from the city, Troy sits on the Hudson but is not technically in the Hudson Valley. Steel was big here, and so were shirtwaists and removable collars — industries that brought a bit of wealth to Troy in the mid-19th century. Though the city started to decline in the 1950s, its Victorian and Greek Revival townhouses and brownstones were mostly spared from urban renewal. About ten years ago, though, Troy showed signs of a turnaround, and the population started to rise for the first time in 50 years.

For Sale

New Troy

“People were like, ‘Why would you leave the Berkshires?’ ”

If you want to put the work in, you can have a Victorian-era building for $1,000 or $5,000,” says Hezzie Phillips, director of the nonprofit arts space the Post Contemporary, who purchased two Neo-Gothic Revival buildings in Troy when she was priced out of her building in North Adams, Massachusetts. “Eight years ago, people were like, ‘Why would you leave the Berkshires?’ They don’t ask me that now.” What initially drew Phillips to Troy was the hint of a budding arts community, led in part by art students from nearby Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. Around the same time, a group of SUNY Albany M.F.A. grads moved over and formed an artists collective called Collar Works, which now runs a nonprofit arts space out of an old collar factory downtown on River Street. In 2005, the Sanctuary for Independent Media, housed in a former church, started offering community-focused arts and science programming, along with an independent radio station. In 2017, the Church Troy, an art studio and event space, opened in another old church; the sanctuary (now pew-free) is used for exhibits. Like Newburgh, this small city has inexpensive but well-designed structures, as well as a land bank that has restored many abandoned properties. The town’s other point of pride is its farmers’ market, which draws upwards of 15,000 visitors every Saturday, including residents of Massachusetts and Vermont who cross state lines in search of pickled vegetables and locally made hot sauce. While Troy’s distance from the city has prevented a total Airbnb-fueled Hudsonification, its burgeoning tech scene, powered by a trio of local colleges (Warner Bros. has set up an office in downtown Troy), is drawing more young people to live in the area full time — and inspiring a lot of them to get involved, including running for city council. “It’s an organic movement,” says Monica Kurzejeski, Troy’s deputy mayor, “but we’re also starting to see what gentrification means. We have enough vacancy in the city right now that we can develop and still maintain people in the neighborhood.”

Locals’ To-Do List

“Sunhee’s Farm and Kitchen is this incredible farm-to-table Korean restaurant. It’s really fresh. They’ve also developed a program to work with refugees — they offer free English classes four days a week.” —Elizabeth Dubben, executive director of Collar Works

“The Narrows is a trail system that will connect one end of the city to the other. They’ve been working on it for three or four years now. A lot of it is open, about 50 percent, and it’ll probably be closer to 70 percent by the end of the year.” —Hezzie Phillips, arts-nonprofit director

“There’s a nicely designed coffee shop and homewares store called Superior Merchandise Company. They do curated events there, like an art-making night; they’ve really helped pull together this scene.” —E.D.

*This article appears in the September 17, 2018, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!