The First Step Act will get a Senate vote before the end of 2018, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell announced on Tuesday. “At the request of the president and following improvements to the legislation that have been secured by several members, the Senate will take up the revised criminal justice bill this month,” the Kentucky Republican said. Hailed as a rare bipartisan effort, the bill is the brainchild of Illinois Democrat Dick Durbin and Republican Chuck Grassley of Iowa. Among its provisions are a softening of federal mandatory-minimum sentencing requirements, retroactive application of the 2010 Fair Sentencing Act — which sought to reduce disparities between crack and powder cocaine possession punishments — and an increase in “credits” inmates can earn to shorten their sentences. The bill is being co-sponsored by legislators as disparate ideologically as Utah’s Mike Lee and New York’s Kirsten Gillibrand. “I’ll be waiting with a pen,” President Donald Trump said in November, signaling his intention to sign the bill into law. “This is a big breakthrough for a lot of people … They’ve been talking about this for many, many years.”

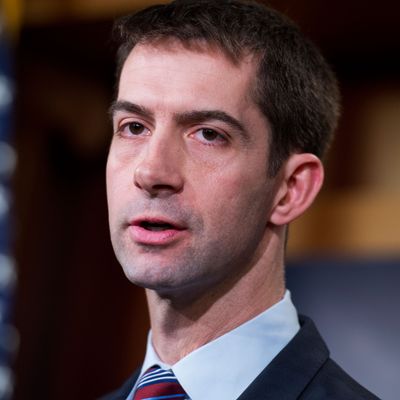

Tom Cotton, certainly, has been. The Arkansas Republican is the First Step Act’s most vocal opponent in the Senate, and a key reason why McConnell was hesitant to take it up in the first place, fearing it would be too divisive within his party. Cotton opposed similar legislation when a related bill died under the Obama administration in 2016. “If anything, we have an under-incarceration problem,” the 41-year-old said during a speech at the Hudson Institute that year. “You’re releasing thousands of serious, repeat, [and] in some cases violent offenders within weeks or months of this bill being passed,” he told Fox News’ Tucker Carlson on Tuesday, criticizing the First Step Act. “It’s almost certain that they’re going to commit terrible crimes.” The recidivism risk posed by shorter sentences has been Cotton’s main talking point, which he has repeated in TV spots, tweets, and op-eds. “[The] First Step Act allows violent felons and sex offenders to be released early,” he said in a statement on Tuesday. “[It] is surprising to me that conservatives … have faith that government bureaucrats can judge the state of a felon’s soul and predict his future behavior,” he wrote for the National Review.

As I’ve written before, the lens of partisan division is wrong for understanding criminal-justice policy. Democrats and Republicans have spent decades united in their zeal for shuffling people in and out of prisons and jails, as evidenced by the steady growth — and racial asymmetry — of America’s incarcerated population, regardless of which party is in power. The First Step Act furthers that bipartisan cooperation, only this time by stemming some of the system’s excesses and easing the torment of federal prison for many incarcerated people and their families. But it is almost comically incremental in the face of such a massive crisis. And much can be gleaned about the worldview of a senator who, facing the prospect of such minor changes and in defiance of many of his fellow conservatives, still insists that the problem is the opposite — that America does not lock up enough people, and that releasing them from prison poses a fundamental threat to public safety because they are likely to reoffend.

Though it is, of course, not possible to know what is in a person’s soul, it is also not necessary to do so to estimate the risk that they will recidivate. Statistics can serve as a guide, as Cotton has indicated by deploying them liberally. The senator would have Americans believe that the First Step Act is going to accelerate the country’s “recidivism problem,” as he described it to Fox News — that, by shortening sentences and releasing prisoners earlier than expected, Americans risk the wiles of the “[five] out of six prisoners [who] end up rearrested within nine years,” as he wrote for the Wall Street Journal in August.

By using arrests as a metric, Cotton is ascribing criminality to people who have not been convicted of crimes, but even had he not, his statistics do not apply to the population the First Step Act addresses. The bill is federal legislation that would apply to federal prisons and jails — which, at 225,000 inmates, house about 10 percent of America’s roughly 2.2 million incarcerated people. This minority is distinct from those incarcerated locally or in state facilities, who Cotton’s statistics describe, in key ways. Among other distinguishing factors, the largest share of federally incarcerated people — 46 percent — are locked up for drug offenses, and overwhelmingly, drug trafficking, compared to 16 percent in local jails and state prisons. According to a study from the United States Sentencing Commission that tracked recidivism over eight years for people released from federal prisons in 2005, about 26 percent of those set free were convicted of another crime within five years — the time span over which the vast majority of such convictions occurred. That rate was significantly higher for people in state prisons, at 44.9 percent.

Considering that Cotton cites statistics about state prisoners to stoke fear about federal prisoners — who, by and large, are convicted of different crimes and recidivate at lower rates — it should surprise no one that he also relies on his own dubious determinations around what constitutes a “violent” offense. “It is naive to think that dealing cocaine and taking part in its import and distribution is ‘nonviolent,’” Cotton spokeswoman Caroline Rabbitt told the Washington Post in 2016, explaining the senator’s opposition to past reforms. “That’s a fantasy created by the bill’s supporters and no serious federal law enforcement expert would agree with it.” Many Americans would probably disagree that selling cocaine amounts to a violent crime. But Cotton’s argument is most appealing where such terms are vague and malleable enough to place a dime-bag sale and decapitating your neighbor in the same rhetorical bucket. The endgame is fear either way. But broadly speaking, the logic fueling Cotton’s philosophy of incarceration — as it can be understood through his public statements — leaves ominously unanswered the question of how far he is willing to go to mitigate all public safety risks associated with recidivism.

Indeed, it is naïve to claim that recidivism is rare, or overwhelmingly benign. People often leave federal or state prisons only to later be arrested, charged, or convicted of subsequent offenses — including many that fit a more widely accepted criteria of violence than Cotton’s. It is also misleading to say that harsher punishment is a reliable deterrent. The data supporting such arguments is inconclusive, at best, and in many cases demonstrates the impact of longer prison terms on recidivism is small, bordering on neutral. But that has not stopped Cotton from accepting the mandatory-minimums logic of crime reduction as self-evident. His opposition to the First Step Act rests on the notion that all incarcerated people are a recidivism risk, and said risk is sufficient grounds to justify keeping them in prison for as long as possible. He may have a point. Theoretically, one can eliminate crime entirely if one is willing to lock up everyone forever. One can accomplish a more modest version of this goal by incarcerating everyone convicted of crimes until they are at least 60 years old, at which point the likelihood of recidivism — which is determined by age more than practically any other metric — is at its lowest. But the truth is most incarcerated people are eventually released. The length of time they spend behind bars varies, but there is no proof it significantly alters the likelihood that they commit future crimes when they get out either way, as Cotton seems to believe. The only definitive solution to the problem Cotton identifies is to ensure that incarcerated people simply stay incarcerated. It is a seductive theory of risk elimination. But it is utterly incompatible with the free society the United States claims to be.