Early last month, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez did a bad tweet. After misreading an article in the Nation on the Pentagon’s accounting errors, Ocasio-Cortez falsely claimed that the Defense Department had wasted enough money over the past two decades to finance 66 percent of Medicare for All. This was an innocent mistake. The congresswoman had cited her source, and linked to it, making it easy for fact-checkers to uncover her error — and thus, for Anderson Cooper to call attention to her “fuzzy math” on this week’s 60 Minutes.

Confronted with her month-old mistake, Ocasio-Cortez replied, “If people want to really blow up one figure here or one word there, I would argue that they’re missing the forest for the trees. I think that there’s a lot of people more concerned about being precisely, factually, and semantically correct than about being morally right.” In the 24 hours after her interview aired, the congresswoman argued that it was unclear what standards fact-checkers use when determining which truths and falsehoods to spotlight — and thus, absent good discretion, fact-checkers could actually bias public discourse by drawing disproportionate attention to progressives’ misstatements.

Throughout these remarks, the congresswoman repeatedly stipulated that factual accuracy was “absolutely important.” On Tuesday, she thanked Politifact for the “work that you do.”

Nevertheless, the spectacle of a socialist congresswoman responding to a fact-check by appealing to the superior importance of moral truth — and then questioning the neutrality of the referees who’d caught her foul — attracted the umbrage of reporters and pundits. Many of their criticisms were valid; others affirmed the legitimacy of Ocasio-Cortez’s complaints.

Here is what the congresswoman’s critics get right: The tax increases that Ocasio-Cortez has publicly endorsed would (almost certainly) not generate nearly enough revenue to fully fund all of her proposed policies. And, in certain contexts, she does obfuscate that fact. For example, when asked how she would “pay” for her platform on 60 Minutes, Ocasio-Cortez could have confessed that she isn’t so sure her policies need to be fully “paid for,” and then attempted to explain Modern Monetary Theory to a lay audience in 30 seconds or less. But it is unlikely that she could have convinced CBS’s viewership that deficits don’t matter — and that the only constraint on public spending is inflation (which the U.S. could probably use a little bit more of right now) — in the time that Anderson Cooper was prepared to give her. Alternatively, she could have stipulated that, while she is committed to lowering middle-class Americans’ overall costs of living, she is also eager to significantly raise their taxes. But that would have (almost certainly) been politically unwise.

So, instead, she observed that, “No one asks how we’re gonna pay for this Space Force. No one asked how we paid for a $2 trillion tax cut. We only ask how we pay for it on issues of housing, health care and education.” This is a sound piece of media criticism. But it also implies that “paying for” Medicare for All — and financing Trump’s “Space Force” — are analogous endeavors. In reality, that latter entity’s initial budget is expected to be “less than $5 billion,” while the price tag for one decade of Medicare for All — according to projections endorsed by Ocasio-Cortez — would be $32 trillion.

In other words: Like every other politician in D.C., Ocasio-Cortez seeks to downplay the potential costs of her policy preferences, while spotlighting their benefits (especially when giving interviews on national television).

That this habit is ubiquitous among politicians does not mean that journalists should indulge it. It’s perfectly legitimate for reporters to ask members of Congress about the trade-offs inherent to their proposals. And when a congresswoman implies that such questions betray an indifference to moral truth, it’s understandable that some reporters take exception.

And yet, Ocasio-Cortez’s critiques of “fact check” journalism are also valid. The nonpartisan political media does often obscure the moral stakes of policy debates beneath semantical nitpicking. And which truths and falsehoods the mainstream press chooses to spotlight — and which it leaves unscrutinized — does reflect the ideological biases of the “objective” press.

To appreciate the former point, consider this critique of Ocasio-Cortez from Washington Post columnist (and newly minted champion of the “vital center”) Max Boot:

Ocasio-Cortez has been particularly inventive, if not especially persuasive, in trying to explain how she would pay for her socialist agenda, including free health care, free college tuition, and jobs. She mystified observers when she said: “Why aren’t we incorporating the cost of all the funeral expenses of those who died because they can’t afford access to health care? That is part of the cost of our system.” That is the kind of word salad you expect from our president.

Reading Ocasio-Cortez’s quote in isolation, one could conclude that the congresswoman has a wild misconception about the percentage of annual GDP that goes toward the funeral expenses of Americans who died from curable illnesses as a result of lacking affordable health insurance. Alternatively, one might intuit that she intended to highlight the human costs inherent to our existing health-care system, as part of a broader critique of the way that the discourse about Medicare for All so often elides the exorbitant moral and economic expense of maintaining the status quo.

Context lends credence to the latter interpretation. Here is Ocasio-Cortez making the case for Medicare for All to CNN’s Chris Cuomo back in August:

[T]he thing that we need to realize is people talk about the sticker shock of Medicare for All. They do not talk about the sticker shock of the cost of our existing system.

You know, in a Koch brothers–funded study, if any study’s going to try to be a little bit slanted it would be one funded by the Koch brothers, it shows that Medicare for All is actually much more — is actually much cheaper than the current system that we pay right now.

… We — Americans have the sticker shock of health care as it is. And what we’re also not talking about is why aren’t we incorporating the cost of all the funeral expenses of those who die because they can’t afford access to health care? That is part of the cost of our system.

Why don’t we talk about the cost of reduced productivity because of people who need to go on disability, because of people who are not able to participate in our economy, because they have — because they’re having issues like diabetes or they don’t have access to the health care that they need.

I think it is fair to say that Max Boot “missed the forest for the trees” in his interpretation of these remarks. Research from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health suggests that when Americans lack access to health insurance, their risk of mortality rises predictably. Extrapolating from that research’s findings, (liberal) think tanks have estimated that hundreds of thousands of Americans will die over the next decade, as a result of lacking access to affordable medical care, absent a change in public policy. It seems reasonable to assume that when Ocasio-Cortez invoked “funeral expenses” on CNN, she intended to highlight these human costs (as opposed to runaway inflation in the coffin sector), while subtly mocking the idea that access to (what she believes to be) a human right should hinge on economistic, cost-benefit analyses. Alas, Boot was too concerned with Ocasio-Cortez’s semantic correctness to discern that her point might not be entirely literal, and that there might be a moral component to her argument.

Notably, while Medicare for All’s proponents are constantly confronted with the fiscal implications of their preferred policy, opponents of dramatically expanding the public sector’s role in health care are rarely confronted with the humanitarian implications of leaving nearly 30 million Americans uninsured. How are you going to pay for it? is a ubiquitous question in our policy debates. How many people are you willing to condemn to preventable deaths in order to avoid raising taxes? is not.

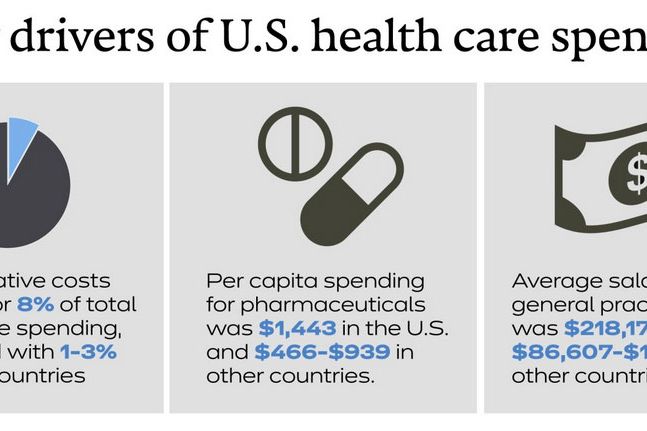

Granted, one could chalk up that disparity to the fact that the precise number of preventable deaths required by our current system is more speculative and contested than the amount of revenue required for implementing Bernie Sanders’s. But the economic costs of maintaining our existing health-care system are even less speculative and contested than Medicare for All’s projected price tag. In 2016, the United States spent nearly twice as much (per capita) on health care as other wealthy nations — and received much poorer health-care outcomes in return. This raw deal is largely attributable to the fact that the U.S. spends several times more than similar nations on health-care administration, pharmaceuticals, and physicians’ salaries.

Any politician who opposes government efforts to drive down these costs (whether by socializing the health-insurance industry or some other means) effectively supports the U.S. dramatically overpaying for drugs, doctors, and health-care administration, year and year out, forever. And yet, such officeholders are never asked to justify this position, or to explain how their vision for American health care is realistic or affordable.

As Ocasio-Cortez suggested in her interview with CNN, the fact that our existing health-care system is exorbitantly expensive is uncontroversial. Last summer, the Koch-funded Mercatus Center found that, absent a major policy change, the American public will spend $59.7 trillion on health care between 2022 and 2031. If the United States adopted Bernie Sanders’s Medicare for All plan, however, the libertarian think tank’s report discovered that the public would spend only $57.6 trillion. Which is to say: A Koch-funded research institute found that socializing the health-insurance industry would save the American public $2 trillion (by forcing health-care providers to accept lower payment rates), even as it extended comprehensive health coverage to nearly 30 million Americans.

Of course, these were not the findings that Mercatus wished to publicize. The aim of their report was to spotlight the enormous increase in public sector health-care spending that adopting Medicare for All would entail. And so, when Matt Bruenig of the People’s Policy Project unearthed the report’s buried findings on overall health-care spending — and Sanders began publicly thanking the Koch brothers for “sponsoring a study that shows that Medicare for All would save the American people $2 trillion” — Mercatus was most displeased. To save face, the think tank implored the mainstream media’s fact-checkers to call out the socialists’ misuse of their work. And the fact-checkers obliged — despite the fact that Sanders’s remarks had been entirely factual. As Bruenig explains:

So how does [CNN anchor Jake] Tapper find an error in a statement that is entirely true? By pretending that Bernie Sanders said something other than what he said. Specifically, Tapper describes Sanders’s claim as such: “[Sanders and Ocasio-Cortez] say that a study funded by the billionaire Koch brothers [shows that] the Medicare for All proposal would actually save the government money.”

Tapper then goes on to debunk the claim that “the government” would save $2 trillion and declare Bernie Sanders a liar, even though Sanders actually said “the American people” would save $2 trillion, which is entirely true.

… Later in the video Tapper acknowledges that the paper says overall health spending would decline by $2 trillion, but then says, “The study’s author says that that $2 trillion drop is not actually his conclusion. He says that’s based on assumptions by Senator Sanders.”

… There are two main issues with this presentation, which Mercatus has skillfully coached a half dozen clueless fact-checkers to repeat. The first is that the provider payment rates in Sanders’s plan are not assumptions … they are written into the law itself. If Sanders says he is going to use Medicare reimbursement rates to pay providers, then that is what he is going to use. Any score that replaces those rates with some other set of rates is straightforwardly not a score of Sanders’s plan. The second is that Tapper is committing journalistic malpractice by credulously believing what [the Mercatus Center] tells him about the study.

Tapper’s insistence that a health-care plan cannot save “the American people” money — unless it saves the American government money — wasn’t some idiosyncratic bit of carelessness. As demonstrated above, it is endemic to how the mainstream media frames debates over public policy. Costs imposed on the American people by the private sector require no justification or defense; only costs imposed by the public sector do. Needless to say, this is not an ideologically neutral stance.

As Mercatus unintentionally revealed, the central question in the debate over whether America should maintain its existing health-care system – or replace it with Medicare for All — is not how much our country should spend on health care. Rather, the question is whether it would be worthwhile for America to reduce overall health-care spending by (at least) a little, provide everyone in the United States with affordable health insurance, and thus, reduce overall mortality — if doing so requires raising taxes (most sharply, on the affluent), imposing cost controls on health-care providers, and euthanizing the entire private insurance industry.

Framing the question in these terms might appear to bias the debate in the left’s favor. But this is only because any plan for redistributing America’s health-care spending away from redundant administration and rent-seeking health-care-industry providers — and toward making coverage cheap and universal — would improve health-care coverage for a majority of Americans, almost by definition. The existing system is substantively indefensible. Other, similar countries have proven beyond a reasonable doubt that the state can effectively coerce lower health-care prices without hurting health-care outcomes. There is nothing substantively unrealistic about Medicare for All. Its most serious liabilities are entirely political. The American public is loss averse, and responsive to anti-tax demagogy. The corporations and interest groups that benefit from the existing system’s inequities and inefficiencies have enormous resources to invest in such demagogy, and in D.C. lobbying. And a lot of ordinary, middle-class Americans are employed by the private insurance industry, and will likely mobilize in opposition to any legislation that threatens their job security.

But “this policy is in the interest of most Americans, but special interest groups oppose it and I’m afraid of them” is not, typically, how politicians like to frame their opposition to politically challenging legislation (there are exceptions). They much prefer to pretend that any legislation that is politically unrealistic is also substantively flawed.

For this reason, a scrupulously objective “fact check” of the substantive claims in the Medicare for All debate would find that the “far left” position is stronger than the center-left and center-right ones (at least, from the utilitarian perspective that’s hegemonic in policy debates). But that conclusion is anathema to the worldview of the “vital center,” and to the conventions of view-from-nowhere journalism. And so, when a libertarian think tank scholar told Jake Tapper that Bernie Sanders was lying — and assured the CNN anchor that opponents of Medicare for All weren’t (effectively) arguing that America should spend more on health care to get less, for the sake of allowing a small minority of (largely wealthy) people to continue benefiting from a broken system — the CNN host took him at his word, and reported his spin as fact.

***

Toward the end of his column on Ocasio-Cortez, Max Boot writes:

For both the far left and the far right, facts are an irksome “detail” of scant importance. What really matters is being “morally right.” If this attitude takes hold among the broader populace, responsible self-government becomes impossible, and radical demagogues will succeed reactionary ones.

This notion — that a political faction’s proximity to the ideological center is tantamount to its concern for empirical truth — has inherent appeal to nonpartisan political analysts. A world in which factual reality consistently lies somewhere between the claims of left and right is a world in which journalists can “call balls and strikes” without compromising their perceived neutrality. But that is not the world we live in. In actually existing America, the “far left” demonstrated a keener appreciation for empirical truth than the center during the debates over whether Iraq harbored weapons of mass destruction; whether more stringent financial regulations were necessary in the early aughts; whether simply expanding public health insurance would prove more effective than creating complicated market exchanges; and whether expansionary austerity is an actually existing economic phenomenon (among many others).

But it is quite easy for the mainstream media to camouflage this inconvenient truth by putting more emphasis on the errors of ideological “extremists” than on those of “moderates.”

In December 2017, Susan Collins told Meet the Press that her avowed commitment to deficit reduction — and support for Donald Trump’s tax bill — were perfectly consistent because “economic growth produces more revenue and that will help to offset this tax cut and actually lower the debt.”

There was no serious evidence to support that extraordinary claim a year ago. And there is now overwhelming evidence that Collins wildly misled the public about the fiscal costs of her preferred tax policy. To their credit, many mainstream news outlets fact-checked the senator’s claim at the time, and have exhaustively reported how reality has contradicted the GOP’s broader claims about the tax bill.

And yet Susan Collins’s willingness to defend a package of tax cuts for the rich and corporations — a policy at the far-right fringe of American public opinion — by claiming that they would actually reduce the deficit has not led the mainstream press to portray her as a fact-averse, far-right extremist. In fact, just last week, the New York Times referred to Collins as one of the Senate’s “most moderate members.”

Ask yourself: Would the sum of total mainstream political coverage lead one to believe that Susan Collins is more committed to realism, ideological moderation, and evidenced-based policymaking than Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez is? And if so, might the latter have cause for questioning the objectivity of the “objective” media?