In these days of permanent campaigning and never-ending election cycles, it’s hard to recall the days when presidential candidates had to be “drafted” by some group of well-wishers. Nowadays most pols who have given even a thought to running for president can be seen with their tongues lolling out, aggressively pushing themselves forward via speaking tours, books, interviews, exploratory committees, massive fundraising, and private polling. That’s why the “Draft Beto” phenomenon is an interesting throwback.

According to Politico, it’s a real, tangible thing:

Beto O’Rourke is getting a significant lift in the early nominating states of South Carolina and Nevada, with operatives in both states joining an effort to draft O’Rourke into the presidential campaign.

Boyd Brown, a former South Carolina lawmaker and former Democratic National Committee member, told POLITICO on Monday that he will become national senior adviser to a “Draft Beto” campaign.

The story said the group is also interviewing staff for the other two “early states,” Iowa and New Hampshire. And according to an Associated Press account, the draft effort has extended into California as well, and has set an initial million-dollar fundraising goal — not that much, but not chicken feed, either. “The Draft Beto organization,” moreover, “says it plans to hold rallies and events in the coming weeks to build support for O’Rourke.”

Presumably the “drafting” supposition is designed to give Beto’s far-flung fans a contact point for the presidential effort that may come soon, and keep his name in the news. But it’s doubtful its central purpose is to talk O’Rourke into running for president — i.e., that it’s a true “draft” of an otherwise unwilling proto-candidate. He’s got plenty of other avenues for discerning how much interest there is in him as a possible 46th president.

The presidential-draft device was more common in the days when the self-assertion of candidates for public office was considered less seemly. And in fact, it has traditionally been most associated with nonpolitical figures whose novelty or popularity the real pols wanted to exploit. A classic example was 1940 Republican presidential nominee Wendell Willkie, a well-known utilities executive “drafted” by a cabal of opinion leaders unhappy with the isolationist tendencies of the GOP’s stable of candidates that year, as Paul Glastris explains:

Sam Pryor, a Republican national committeeman from Connecticut, wrested control over what was, in those days, one of the key resources to winning the nomination: tickets into the convention hall. Media mogul Henry Luce used his magazines to promote Willkie’s candidacy shamelessly. New York Herald Tribune book editor Irita Van Doren, Willkie’s mistress, helped the candidate hone his message. A young lawyer named Oren Root Jr. organized Willkie Clubs around the country.

And eventually, carefully packed galleries chanting “We Want Willkie” stampeded a deadlocked national convention to nominate this political novice on its sixth ballot.

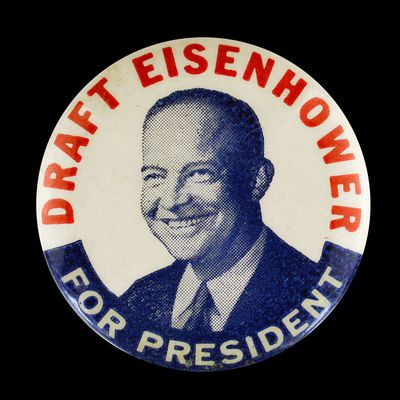

After World War II, former Allied Supreme Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower was the object of not one but two genuine “draft” efforts, one in each party. In 1948 President Harry Truman privately offered to step aside and even run as Eisenhower’s vice-presidential ticket mate if the general would agree to lead the Democratic Party. He demurred, but in 1952, Republicans — led by two-time presidential nominee Thomas Dewey and prominent Senator Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. — were more successful, as the Eisenhower Institute recalls:

On January 6, 1952, Lodge forced the issue by entering Eisenhower in the New Hampshire Republican primary without Eisenhower’s authorization. The press demanded a response. Eisenhower therefore issued a statement on January 7th that if offered the Republican nomination for the presidency, he would accept.

After a monster rally at Madison Square Garden and then an in absentia win in New Hampshire, Ike finally joined his own presidential campaign and rolled on to the presidency.

Having played such a central role in the Draft Eisenhower movement, Lodge was himself the object of a similar effort in 1964 when a group of volunteers launched a New Hampshire primary write-in campaign for the then–U.S. ambassador to South Vietnam, appealing to Republicans unhappy with a choice between liberal Nelson Rockefeller and archconservative Barry Goldwater. Lodge won handily, before losing an Oregon primary to Rockefeller that he was favored to win, and then dropping out without ever having actually campaigned.

The last real presidential draft effort hearkened back to the Eisenhower tradition, when antiwar Democrats gradually talked former NATO commander Wesley Clark into running in 2004. The “Draft Clark” movement became known for its innovative, web-based organizing and fundraising technique, but the general did less well when he actually ran; he skipped the Iowa caucuses and could never catch John Kerry after that.

Since then, there have been momentary efforts to draft a candidate at perceived crisis points facing one party or the other. “Draft Jeb Bush” talk popped up in 2012 when it looked like Newt Gingrich or Rick Santorum might block Mitt Romney’s path to the GOP nomination. And in 2015 there was a well-organized and visible effort to draft Elizabeth Warren to run as a progressive alternative to Hillary Clinton before Bernie Sanders emerged strongly to seize that role.

It’s unclear how the “Draft Beto” effort fits into the history of presidential drafts. He’s not a war hero like Ike or Clark, or any other sort of non-politician type, but a professional pol who until very recently served in the U.S. House of Representatives. He’s not a senior party figure with a very familiar name, like Lodge or Jeb Bush. And he’s not someone being summoned forward to fill a vacuum in a sparse presidential field, like Warren in 2015, but instead one of an enormous cast of characters forming for the 2020 nomination contest.

O’Rourke isn’t much playing the reluctant candidate, either. Freed from public office, he’s about to embark on what is usually called a “listening tour” to keep himself in the public eye and gauge enthusiasm for a likely run. Before long he will probably feel the draft and move toward an active candidacy or decide to do something else with his immediate future (like another Senate race in Texas) that precludes a presidential campaign. For a brief time, though, Draft Beto may be real.