Last weekend, the Washington Post published a story titled “Democrats’ Tax Plans Reflect Profound Shift in the Public Mood.” This was not an opinion piece, but rather, a straight report with an analytical frame. Which was odd, since the article offered no real evidence in support of its (ostensibly objective) headline.

After describing the Democratic Party’s various new ideas for soaking the rich — from Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s 70 percent top marginal income tax to Elizabeth Warren’s wealth tax to Bernie Sanders’s turbocharged levy on trust-fund kids’ inheritances — the Post’s Matt Viser wrote that the “proposals reflect a broad shift in the mood of the Democratic Party and the country more generally, as the recent financial crisis and a distrust of big institutions has fueled a populist surge in both parties.”

To substantiate this claim, Viser cites exactly one poll — a Pew survey that shows a modest populist shift in the mood of Democratic voters, but none whatsoever in the mood of the country:

Nearly two-thirds of Americans believe the U.S. economic system unfairly favors powerful interests, a figure that has changed little since 2014, according to polling from the Pew Research Center.

But the proportion of Republicans who believe the system is unfair has dropped significantly — from 51 percent in 2014 to 36 percent now — while it has increased among Democrats, from 71 percent to 84 percent.

Now, it’s true that recent polling has upended the commentariat’s assumptions about public opinion on tax policy. Last week, Starbucks billionaire Howard Schultz argued that the Democratic Party’s radical tax ideas had opened up space for a centrist presidential candidate to unite Republicans and Democrats around common-sense, bipartisan solutions; days later, polls revealed that Elizabeth Warren’s proposal to annually expropriate 2 percent of Schultz’s wealth was a common-sense, bipartisan solution.

But the fact that pundits deemed these findings surprising tells us less about American opinion than it does about American pundits. The U.S. public has (just about) always been eager to soak the rich. In April 2018, Gallup found 62 percent of Americans saying that upper-income people pay too little in taxes. Here is the trendline for that question between 1992 and 2016:

Thus, the Post’s analysis isn’t rooted in evidence, but merely in the presumption that changes in partisan positioning on Capitol Hill must reflect shifts in popular opinion. This presumption isn’t unusual. It’s pervasive in nonpartisan political analysis — despite the fact that it holds up under scrutiny about as well as Donald Trump’s philanthropy.

A moment’s glance at the chart above should be enough to disabuse one of the idea that there is a tight correlation between policy outcomes and popular preferences. When George W. Bush rallied bipartisan congressional support behind a giant tax cut for the wealthy in the early aughts, the American public was just as eager to soak the rich as they are now (while just 10 percent said the wealthy deserved a tax cut). On the other hand, the high-water mark for popular Jacobinism in the last quarter-century was, apparently, the early 1990s — which was not exactly a moment of peak influence for left-populists in the Democratic Party.

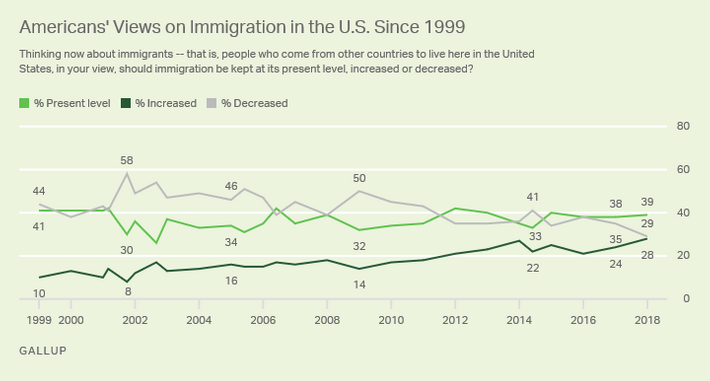

Nevertheless, the political media’s habit of equating shifts in policy paradigms with changes in public opinion persists. No small amount of commentary over the past three years has presumed that Donald Trump’s rise reflected a nativist turn in the general public’s mood. But that turn appears nowhere in public polling.

The American public was much more hawkish on immigration when George W. Bush was pushing for mass amnesty than it is today. In fact, support for immigration restriction has been weaker in the Trump era than it was throughout the 1980s — a decade when two consecutive Republican presidents enacted bipartisan legislation extending amnesty to the undocumented and increasing legal admissions.

The fact that public opinion does not (typically) drive ideological realignments — and the mainstream media’s aversion to recognizing this fact — might be best illustrated by the Reagan revolution. In mainstream discourse, it’s taken as a given that the American right won an argument against New Deal liberalism in the 1980s — and that public support for “small government” became so strong, Democrats were only able to win back the White House by disavowing their old “big government” ways.

But as the political scientists Thomas Ferguson and Joel Rogers document in their 1986 book Right Turn, public support for government intervention in the economy was high — and rising — throughout Reagan’s first-term:

A Los Angeles Times poll in 1982, for example, asked respondents if they would favor “keeping” or “easing” regulations that President Reagan “says are holding back American free enterprise.” Even with the question posed this way, the percentage favoring “keeping” outweighed that favoring “easing” regulations regarding the environment (49-28%), industrial safety (66-18%), the teenage minimum wage (58-29%), auto emissions and safety standards (59-29%), federal lands (43-27%), and offshore oil drilling (46-29%). In 1983, the Times again asked about regulatory policy, finding that only 5 percent of Americans found regulations “too strict,” while 42 percent thought they were not strong enough … Comparing the results of a 1982 survey with one commissioned in 1978, the Chicago Council on Foreign Relations found a remarkable 26 percentage point jump in those wishing to “expand “ rather than “cut back” welfare and relief programs…By early 1983, a CBS News/New York Times poll found that 74 percent of the public supported jobs program even if it meant increasing the federal deficit.

One might argue that all this survey data must be flawed — after all, voters who held such beliefs would never have reelected Reagan by a landslide margin. But red-state electorates are constantly formally declaring their opposition to core Republican policy goals by passing minimum-wage hikes, labor protections, and Medicaid expansions through referenda. In many cases, their elected leaders then roll back the duly enacted ballot measures, and/or pursue policies directly contrary to their constituents’ ostensible preferences. Then, those Republican officeholders (typically) win reelection.

All of this reflects a simple truth: The “popular will” does not generally drive policy changes in the United States; shifts in the balance of power between organized interest groups do. American economic policy veered sharply to the right in the late 1970s because that decade’s high rates of inflation — and (relatively) low rates of profit — turned corporate America more conservative, at the same time that the most reactionary wing of the GOP donor class successfully recruited the Christian right to its cause.

The GOP’s immigration policies were (relatively) dovish in the 1980s because the party’s (pro-immigration) corporate Establishment had firm control over its agenda. The rise of right-wing talk radio, Fox News, and blogs loosened that Establishment’s grip on the party, and enabling the GOP to move right on immigration, even as public opinion drifted left.

Similarly, the Democratic Party didn’t triangulate on economic policy in the 1990s in response to mass popular support for financial deregulation or capital gains tax cuts. Rather, they did so because organized labor was in decline, while the financial industry was ascendant — and thus, so too was the Wall Street wing of the Democratic Party. Since then, the advent of social media and small-dollar fundraising has made it easier for the Democratic left to disseminate its message, win primary elections, and call attention to the fact that many of its “radical” ideas are (and have long been) extremely popular.

The mainstream media’s faith in the relevance of public opinion to major policy changes is understandable. In a democracy, political legitimacy is supposed to derive from popular sovereignty. Thus, to accurately describe American civic life — to acknowledge the median voter’s capacious ignorance of each election’s policy stakes, the Republican Party’s success at winning elections while holding its own voters’ economic preferences in contemptuous disregard, the unseemly influence that economic elites wield over both sides of the aisle, the arbitrary and anti-democratic structures of the U.S. government, and the consequent fact that ordinary Americans do not exercise anything resembling self-rule — would be tantamount to challenging the legitimacy of the existing political order. And that is not what mainstream, nonpartisan political analyst are paid to do.