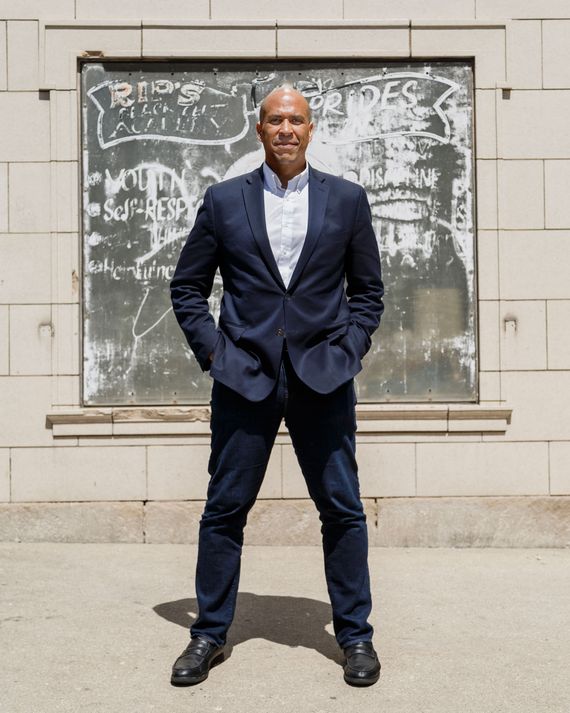

“I’ve run for three offices in my life — this is the fourth — and it was a massive issue when I ran for city council. My pollster said he’d never seen anything like it — it was the No. 1 concern when I ran for mayor of Newark the first and second time: safety, violence,” says Cory Booker. We’re sitting on an Amtrak train from Milwaukee — where Booker’s just wrapped up a roundtable discussion on gun-violence prevention in a coffee shop — to Chicago, and Booker is trying to make sure I understand how central the issue is to his political career, and what he wants to do now. The New Jersey senator and former Newark mayor is in the middle of a high-intensity campaign swing hitting a series of politically important states — Donald Trump will visit Wisconsin four days later — where he’s talking about a wide range of politically potent issues (voting rights, criminal justice, environmental justice …) as he looks for some much-needed momentum heading into the summer, when the party’s debates will begin. Booker is a few months into his presidential campaign, and he’s recently started publicly bristling at the way compromise is being treated like a bad thing, and how progressive purity tests are fashionable now, as he looks to break away from the overstuffed pack of candidates. In Milwaukee, he sat with a small group of gun-violence survivors and activists to hear their stories, vowing to fight the NRA and promising that finding creative solutions to the issue would be front and center in his White House. On the train, he recounts how, when he ran for Senate for the first time, he insisted to his pollsters that criminal-justice reform and gun policy would again be his priority. “How could it not be an issue?” he asks. Which brings us here.

——

We just came from a pretty powerful discussion about gun policy. Are there any things you’d be willing to do with the powers of the presidency — executive powers — that previous Democratic presidents haven’t been willing to do on that front? What would you do that goes further? Presumably, if control of the Senate doesn’t change, it would be tough to pass what you want, right?

This is a tough one for me because I’m not going to telegraph my punches on a fight like this. There are definitely things that I think any president —that I could do as president — that would bring this fight more creatively, in a more impactful way.

So do you see room where a President Booker could actually work with the Senate on guns, then? As currently constituted, it’s not exactly willing to move on this issue right now.

No, but I don’t know what the Senate’s constitution will be, so it’s hard to speculate. I mean, Toomey-Manchin was a bill that would’ve made progress. And that was coming from, you know, a bipartisan space. So I don’t know what the Senate will look like, but I think there’s a lot of tools on the table we can use to win this fight.

All right. Is this, then, your philosophy on policy generally speaking, or gun violence and gun control specifically?

You have to play the hand that you’re dealt. But what I was successful doing in Newark was changing the rules of the game. We couldn’t get institutional capital into Newark, we couldn’t get philanthropy. We just had to create ways, using devices like that, to make Newark a national story, which it never had been, which suddenly changed the field to me. A lot of it was just creative thinking. And frankly, Trump has done that. He’s disintermediated the media, he’s used very different tactics to achieve, I would say, sinister results. But he’s a guy that hasn’t played by the rules as you would in Washington, and I didn’t play by the rules — as we knew it, as they were meant to be — in Newark.

Sure, though in terms of legislation, it’s not as if he’s been the most effective president, at least as far as big-ticket legislation goes.

No, definitely not. And I’m proud to have worked with this White House on criminal-justice reform, I consider that a big accomplishment.

Did that experience teach you anything about the way Trump works? I assume you weren’t talking too much about the bill’s language with him, but …

I give credit to people like Jared Kushner on that. We built a really good coalition, I’ve been talking to the Koch brothers’ general counsel for years before that, [Mark] Holden.

You knew Kushner before, too. That presumably helped?

It was definitely … By the time I got to the Senate I was meeting with Grover Norquist in my office, with Newt Gingrich in my office. Every ally I could find on the other side of the aisle, and willing to do — have conversations that I think some people aren’t willing to sit down and have. It’s really one of those wonderful things where I come from a community where it’s the No. 1 issue, get to the Senate, even under this president, pass something that deals with this. It’s the things that keep you going.

So did this experience give you any insight into how Trump actually thinks?

No. I know Jared has been driven about this issue since his father’s experiences. And we had already created — before Trump was even elected — a bipartisan coalition, we got it out of the Senate Judiciary Committee, it would’ve passed on the Senate floor if McConnell was willing to put it there under Obama. So the raw materials were already there, and Jared did the job of creating the will in the White House.

There’s immense skepticism out there, obviously, about getting this kind of bipartisan support on basically anything else, but especially when it comes to anything having to do with Trump, like continuing the investigations into him or setting up hearings. What do you make of the common argument: Listen, we have an election coming up, we don’t need to turn impeachment proceedings into a partisan fight, let’s just get the election done and oust him that way?

I know it’s hard to say this, and you may give me a skeptical look, but I don’t think we should look at this — a president breaking laws — through a political prism. I really don’t. I think that’s one of the problems we have, I think we need to follow a process that involves getting the underlying documentation of the Mueller report, getting Mueller to come before Congress, by the way, seeing a full unredacted version of the report. I think all these things should lead us to conclusions. So I try not to let my partisan instincts in, to look at this as a very sobering moment in American history, that we have a president who, not only the people around him have been indicted and convicted in the campaign and the administration, but you read a report and it speaks to criminal activity. I think there should be a process independent of politics and that really focuses on what the roles and responsibilities are.

Okay, so what does that look like next, for you? When you go back to D.C. what are you going to demand comes next?

I already am, I’ve been speaking about needing to see the full report, being able to interview Mueller, and it’s really important — I think that can be really valuable. Barr is less valuable, he’s lost a lot of credibility in my opinion, in terms of his independence.

Did you have much hope for him?

Did I have much hope? I mean, yeah, I had hoped that he would answer the moment in history! To understand this is a brief moment in time and he will be judged by people decades and decades from now, and I think he’s going to be judged poorly. So I had hoped that he would prove not to be the president’s lawyer, but prove to be an independent attorney general.

One of the reasons I’m asking about this is because I’m curious about your analysis of the overall tenor of D.C. right now. Are you confident at all that if Mueller comes forward and testifies, if there’s an ability to get more of the report unredacted and seen by enough people in Washington, that there would be a real change in tone, or that you might have Republicans start to talk about this differently?

I don’t know. I really don’t. I mean, clearly you’re seeing people who are loath to criticize behavior that if they saw it in a president that wasn’t of their party they would be over the top on. You saw the way they treated investigations into Obama, investigations into Hillary based on things that any objective person would say are quite small compared to what we’re seeing now. But I think a lot of it also depends on what the public does, how the public reacts. So I wouldn’t say I have high hopes for that, but I do think it’s important to put as much truth out there as possible, to test people’s patriotism.

How did your life in the Senate change after you testified against Jeff Sessions — the first time a sitting senator had ever testified against one of his colleagues?

Before I got to the Senate people thought I was gonna be some kind of hot dog because so much of my job as the mayor of Newark was to get attention to Newark, to get people who wouldn’t come or pay attention to come. I’m a guy who, one of my earliest conventions, in Las Vegas, I was getting laughed at when I was talking to people about coming to my city. So we found very creative means to get people’s attention to our city, getting in a fight with Conan O’Brien to using Twitter like it had never been used before. But that was a means to an end. In the Senate, for me, I had earned a lot of — I wouldn’t even do interviews for the first full year. By that time, with Sessions, enough people saw me as a workhorse that it didn’t [change anything]. I mean, a couple of Republicans, I think, got a little [tough]. But I did what Bill Bradley told me to do, which was go sit down with, have dinner with Republicans. I was going to Bible studies. So people see who you are.

You’ve talked about how when you first got to Washington there was concern you’d be a showboat, but beyond that, there was a “He’s going to run for president someday” assumption around you, too. How did that shape the way you chose to act in the Senate? Have you thought about it a lot?

No, I mean, I’ve got friendships where if people saw me [with that friend,] I would take an easy political hit. Instead I suck it up, it’s the right thing to do. I think people got a chance to see that a lot in me, and I think it defused a lot of the stuff that was there when I first got there. Heidi Heitkamp still teases me about being so different than the guy she expected to show up in the Senate. So I mean, even now, a magazine put an angry picture of me up when I was going after Kirstjen Nielsen, and one of my most conservative colleagues came up laughing and asked me to sign it. I signed it, of course! Because he knows the way I was being portrayed is so far from the truth, you know? So I feel good that I’m in the body now that I have great friendships and relationships with people. That doesn’t mean we don’t fight, I mean clearly the Kavanaugh hearings was where we all went at each other. But the great thing about that, afterwards, is some of the people on the Judiciary Committee were essential for me getting the last thing I was trying to force into that [criminal justice] bill, which was a ban on solitary confinement. Some of the same people who, it looked like, we were going at it during the Kavanaugh hearings, we had a relationship to partner up literally days later to get a big provision I wanted to get in.

While we’re on the Kavanaugh topic, I know you’ve talked with a lot of skepticism about the idea backed by some of your rivals to pack the Supreme Court, or expand its size. But let’s say you become president and Republicans hold the Senate, do you have any confidence you would ever be able to get a Supreme Court justice confirmed? Or …

I mean, the deterioration of the Senate right now, who knows where we’re going to be? Could I get a secretary of State confirmed? I mean, I don’t know where we’re going, I really don’t. This is a point where a lot of us on the Senate floor are talking very openly about, like, how do we stop this deterioration of this body? So I can’t tell you what the cards I’ll be dealt will be, going back to that metaphor. But I know that the presidency has never seen an X-Gen-er sit there. We will bring a lot more creativity in getting problems solved, at least I know I will. I’ve had to find a lot more creativity to do things that people told me would be impossible to do in Newark, that they told me they would never live to see in our city.

But then the answer is just, We’ll have to just wait and see?

Yeah, I mean, trust me. Now that I’m running for this office, I sit and think a lot about what the tactics are going to have to be, playing out scenarios, thinking who the key allies will be. You know, who can I work with?

Who can you work with?

Where do I start? I’ve found partners on so many different issues. There are people you can work with, but you have to know their parameters. I still remember there have been times where I’ve had people who worked with me really suffer in their primaries, and that’s unfortunate. Yeah, it’s unfortunate when Republicans are doing the right thing to help their community, and then they find pictures of me and the person coming back to haunt them.

Do you think that’ll happen to you in this primary? You’ve had dinner with Ted Cruz, sat down with Lindsey Graham …

I welcome it! If that’s how I’m going to be taken out in a Democratic primary, if that’s really a sin in this, I will not be the nominee, and that will be fine. Look, I value comity, I value finding common ground. We are not going to heal this country, whether it’s farmers or inner-city restaurant workers, we’re just not going to get the big things done if we can’t find ways to cross the aisle.

One place where you’ve had common ground with at least some Republicans is education policy. You’ve talked a lot in the past about charter schools, but not so much these days. Is that because the political ground has shifted?

No, it’s just a different job. I was a mayor, I wanted to get every one of my kids — I had 50,000 kids, not even a big number — in an excellent school. You’re a black kid in my city from the time I was mayor until now, your chances of going to a school that beats the suburbs, like Princeton or Summit, went up 300 percent. We kicked ass, and some of that actually was closing charter schools — I advocated the state to close my low-performing charter schools. Some of that was closing district schools. So for me that was just, “What are the tools I have to get every one of my 50,000 kids into a school better than I went to?” And as a senator, I mean, charter schools come up when I talk to the D.C. mayor, I mean, that’s my purview. I met with the mayor a couple weeks ago to talk about, among so many things, education, helping her get a bill through that would get her much more money if we did it, if Republicans like that bill. This is a case where we’re not taking a dollar away from public schools, you’re actually getting them more. So my short on that is, as a senator I’ve put a massive education bill forward that’s going to help all local public educators.

But I don’t know what to tell you if the landscape is shifting or not. I know if you stood in the black community in some states, their views on charters are horrible, but that’s because Republicans wrote their charter bills. I would be fighting against those charter bills, from what I’ve heard. I haven’t read them in detail, but South Carolina’s schemes, I call them, more than real charter bills or voucher schemes, are just like, damn it. So on this trail I talk about education policy in states like Iowa and South Carolina, which are Republican-controlled governors that are trying to push things under the guise of being what we did in Newark, which are a whole different animal.

Have you talked to Mark Zuckerberg since you worked with him as mayor and he put $100 million toward education in Newark?

Yeah, absolutely, he came to testify. That was a public forum, but of course I reach out to him. At the end of the day, he’s still a friend. Doesn’t mean I agree with everything he’s doing.

Well, that’s where I was going.

Why does my politics have to mean I have to stop being friends with Mark Zuckerberg or Chris Christie?

Or Jared Kushner?

Or Jared Kushner. Well, that was a different story. Let’s leave Jared aside, that’s a lot different. But no, I mean, this is what I mean about a revival of civic grace and having forgiveness. This idea that we can’t talk to each other, this idea that we can’t touch each other. I mean, Christie lost over 10 points in New Hampshire because they just ran a video of him hugging Barack Obama. When I hugged John McCain after he came on the floor, I go home and I’m getting torched on Twitter. It’s so funny, I think my hashtag was #IhuggedJohnMcCain. I found it so absurd that we would come to a point where we can’t talk.

So I have a lot of constructive criticism about oligarchies and concentrations of power. Is it a good thing that few companies control [so much] percent of online advertising? These are conversations that we can have. Are the algorithms that Facebook is using having disparate impact or racialized impact? These are conversations we can have.

Or, have they taken enough responsibility, or changed their policies sufficiently, after what happened in 2016?

Yes, these are all things. But to sever, because of politics, even dialogue?

Okay, so what do you think on these questions?

I feel very strongly about them! I feel very strongly about privacy issues and how my data is being used now. I mean, I can’t believe cable companies came to Washington and basically got permission — I’m already paying them for cable — now they can actually, and this is not even like Facebook, I’m paying you for cable, and now you’re going to use my viewer information as another profit source? Data of mine? So these are issues I feel very strongly about, have real constructive critiques about, whether it’s Silicon Valley or Pharma or Wall Street or cable companies or credit card companies or mortgage companies.

I mean, it all comes back, to me, to the lens of why I got started in politics. The inner city, central ward of Newark, New Jersey, which is the lens that helps me have more courageous empathy for farm and rural communities, have more courageous empathy for factory towns, for coal miners. For me it’s very simple, it goes back to people who helped me get elected to my first office: Don’t forget where you came from. So of course I’m going to call those institutions out, but at the same time when I was mayor and I needed to build the first hotel in our city in four years, I went to the banks. What’s the old saying, “Why do you rob banks? Because that’s where the money is.” Why did I go to Wall Street to help build a hotel? Because I needed the institutional capital, and to do it on my terms, too, which meant apprenticeship programs, union construction, and a lot of other things. So that’s what I meant in my kickoff speech about, are we going to let some kind of purity test undermine progress? Have you shaken hands with somebody — is that going to tank my political career, when I run for the presidency, that I have relationships with people who helped me get things done in Newark? That got Newark teachers a raise? That’s what most of the money from the Zuckerberg thing went, to give teachers higher salaries.

So I have little patience for that, and, again, this is one of the most freeing moments of my life because I can get up every single day and my job is to be as authentic as I can. I end up talking about love and the kinds of things you just saw there, which maybe doesn’t sound like a normal presidential campaign. That’s fine, because people should know who I am and what motivates me, being the only guy in the United States Senate who, for 20 years, has lived in communities like the one we just came from. I’m going to let people know what drives me, what motivates me every single day. So.

When it comes, specifically, to the Wall Street question, do you regret, or ever think back to, the moment during the 2012 campaign when you spoke up about the private-equity industry …

From “Spartacus” to Wall Street, I wish people would go back and actually listen to exactly what I was actually saying. The Spartacus moment, I was talking about Dick Durbin, who just basically said, “If you throw [him] in the hole, throw me there too.” I was like, “Dick Durbin, you are frickin’ heroic.”

So I get rankled a little bit with the hypocrisy within my own party sometimes. That was a case where I battled to get my unions and people who were going to produce returns. I’m not going to defend [the entire private-equity industry]. I’m going to go after the practices of private equity I think are wrong, I did this recently with Toys “R” Us, which I felt was awful. And I think we should have rules that work. But I’m sorry, I’m not anti-capitalist. As a guy who’s been trying to start small businesses, I’m anti-corporate cronyism and the kinds of things that I think are not making us a small business, entrepreneurial culture, which we need to get back to. But I’m a guy that does not have the luxury, in a community where you have shootings and mass incarceration and lead in my water and high rates of poverty, I don’t have the luxury to fit into everybody’s — some people’s — purity tests, when I’m trying to build a damn hotel. When I’m trying to build a $130 million teachers’ village. My point is that there’s an urgency, that’s really why we put our kickoff speech to, like, we just can’t wait. I have an urgency about getting things done. If that means that my first move on criminal-justice reform is just one step in a journey, it is so much better than not taking that step at all. And, you know, when people come up to me on this Wall Street stuff? You know, my staff told me some nonprofit from D.C. said I had voted with Wall Street zero times in my six years in the Senate. Zero times. So please, people, just judge me by what I’ve done.

I’d rather do interviews like this in my neighborhood, because I can walk with you and show you: We built that park on philanthropy, we brought that supermarket here because it was a complicated capital stack I had to fill with this creative use of financing. I would show you things I’d done that were making a massive change in lives, and in the interview I would introduce you to people and say, “What do you think of that park?” or “What do you think of that school?” And all those people would tell you what was there before. We did that because we were just creative, we had a sense of urgency, we created uncommon coalitions to achieve uncommon results. I got this great grant as Bush was going out the door on criminal-justice reform, because I was able to find somebody who knew somebody in the Bush administration. It’s like, figure out, connecting dots. Because in my community, they didn’t care if it was a Bush administration grant or an Obama administration grant. It helped a whole bunch of African-American people coming home from prison to get jobs.

This article has been edited and condensed from an extended conversation.