For a while, the possibility that the U.S. Supreme Court would find partisan gerrymandering to be unconstitutional rested in the hands of Anthony Kennedy, a swing justice who seemed offended by the practice but could never quite find a method he liked to measure or remedy it. With his retirement last year, Court watchers figured the odds of the justices doing something about it had dropped significantly. Today they dropped to zero, as NPR’s Nina Totenberg succinctly explained:

Prior to Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s appointment to the Supreme Court, Justice Anthony Kennedy was the swing vote on this issue. He seemed open to limiting partisan redistricting if the Court was presented with a “manageable standard.” But with Kavanaugh on the Court, the search for that standard is over.

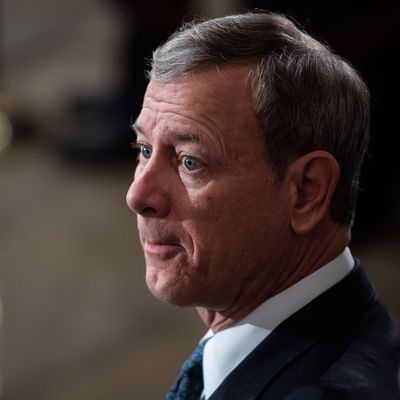

Writing for the new 5-4 conservative majority on the Court in two combined cases (Ruccho v. Common Cause and Lamone v. Benisek), Chief Justice John Roberts argued that partisan gerrymandering, while offensive to traditional notions of democracy, was a “political issue” best left in the hands of political branches of the federal and state governments.

Federal judges have no license to reallocate political power between the two major political parties, with no plausible grant of authority in the Constitution, and no legal standards to limit and direct their decisions.

There wasn’t much doubt in the cases before the Court that Republican legislators in North Carolina and their Democratic counterparts in Maryland had drawn district lines purely and simply to maximize partisan outcomes. In North Carolina, in particular, GOP legislators openly spoke of their plans to screw over Democrats in congressional redistricting, in part to rebut (or perhaps simply disguise) racially invidious motives that would invite judicial intervention. And as Justice Elena Kagan emphasized in a scathing dissent joined by the Court’s other liberals (Ginsburg, Breyer, and Sotomayor), the majority admitted partisan gerrymandering was a travesty:

[T]he majority concedes (really, how could it not?) that gerrymandering is “incompatible with democratic principles.” Ante, at 30 (quoting Arizona State Legislature, 576 U. S., at ___ (slip op., at 1)). And therefore what? That recognition would seem to demand a response. The majority offers two ideas that might qualify as such. One is that the political process can deal with the problem … The other is that political gerrymanders have always been with us.

Indeed, Roberts suggested federal and state legislatures could police partisan gerrymandering more effectively than could federal courts, but Kagan put her finger on the emotional core of the conservatives’ argument: Political gerrymanders have always been with us. But the circumstances have entirely changed, she observed:

Yes, partisan gerrymandering goes back to the Republic’s earliest days. (As does vociferous opposition to it.) But big data and modern technology — of just the kind that the mapmakers in North Carolina and Maryland used — make today’s gerrymandering altogether different from the crude linedrawing of the past. Old-time efforts, based on little more than guesses, sometimes led to so-called dummymanders — gerrymanders that went spectacularly wrong. Not likely in today’s world. Mapmakers now have access to more granular data about party preference and voting behavior than ever before. County-level voting data has given way to precinct-level or city-block-level data; and increasingly, mapmakers avail themselves of data sets providing wide ranging information about even individual voters.

In view of the majority’s hard-line opposition to getting into the subject, the growing sophistication of partisan gerrymandering, and with it the ever-more-severe practical disenfranchisement it enables, isn’t going to matter any more in the future than it does right now. So what this decision does as a practical matter — beyond launching celebrations among the Republican lawmakers and lawbreakers who control a majority of the country’s state legislatures — is direct concern over gerrymandering into different channels.

The silver lining of the Supreme Court’s retreat from interest in partisan gerrymandering is that it has led the Court to defer to recent efforts to attack the practice on state constitutional grounds. That’s what happened last year when the Pennsylvania Supreme Court struck down a GOP-drafted congressional map and substituted its own: As Republicans everywhere howled, the U.S. Supreme Court shrugged and refused to review the case. Today’s decision obviously leaves open the avenue of state redistricting reforms (whether undertaken by legislatures or ballot initiative) that drastically limit politically motivated discretion in redistricting procedures. But the timing is inauspicious for slowly building momentum for redistricting reform with the decennial Census and the next round of map-drawing just around the corner.

No matter what happens at the state level (or in Congress, which could theoretically limited partisan gerrymandering in federal elections), the decision is deeply dissatisfying to anyone who believes justice should be the overriding motive of the Supreme Court in cases touching on the most fundamental rights. And that was the real travesty of Robert’s decision, as Kagan rightly pointed out:

For the first time ever, this Court refuses to remedy a constitutional violation because it thinks the task beyond judicial capabilities.

And not just any constitutional violation. The partisan gerrymanders in these cases deprived citizens of the most fundamental of their constitutional rights: the rights to participate equally in the political process, to join with others to advance political beliefs, and to choose their political representatives. In so doing, the partisan gerrymanders here debased and dishonored our democracy, turning upside-down the core American idea that all governmental power derives from the people.

Anthony Kennedy should be ashamed of himself for taking a pass on the opportunity to deal with this problem before heading off to retirement. It may never again arise in the U.S. Supreme Court.